Vertical Atlas started four years ago with the mission to create an atlas to help navigate the worldwide digital transformation and its complex effects at different locations and on a variety of scales. A group of artists, academics and technologists from various fields and places around the world collectively and individually researched, investigated, narrated and compiled their insights in this book. As such, it makes explicit the many exploratory paths and collective knowledge of people and communities working on redefining how technological worlds are seen and visualized. The contributions are from people who have all had different practical and personal experiences of the implications of the digital transformation and its global effects.

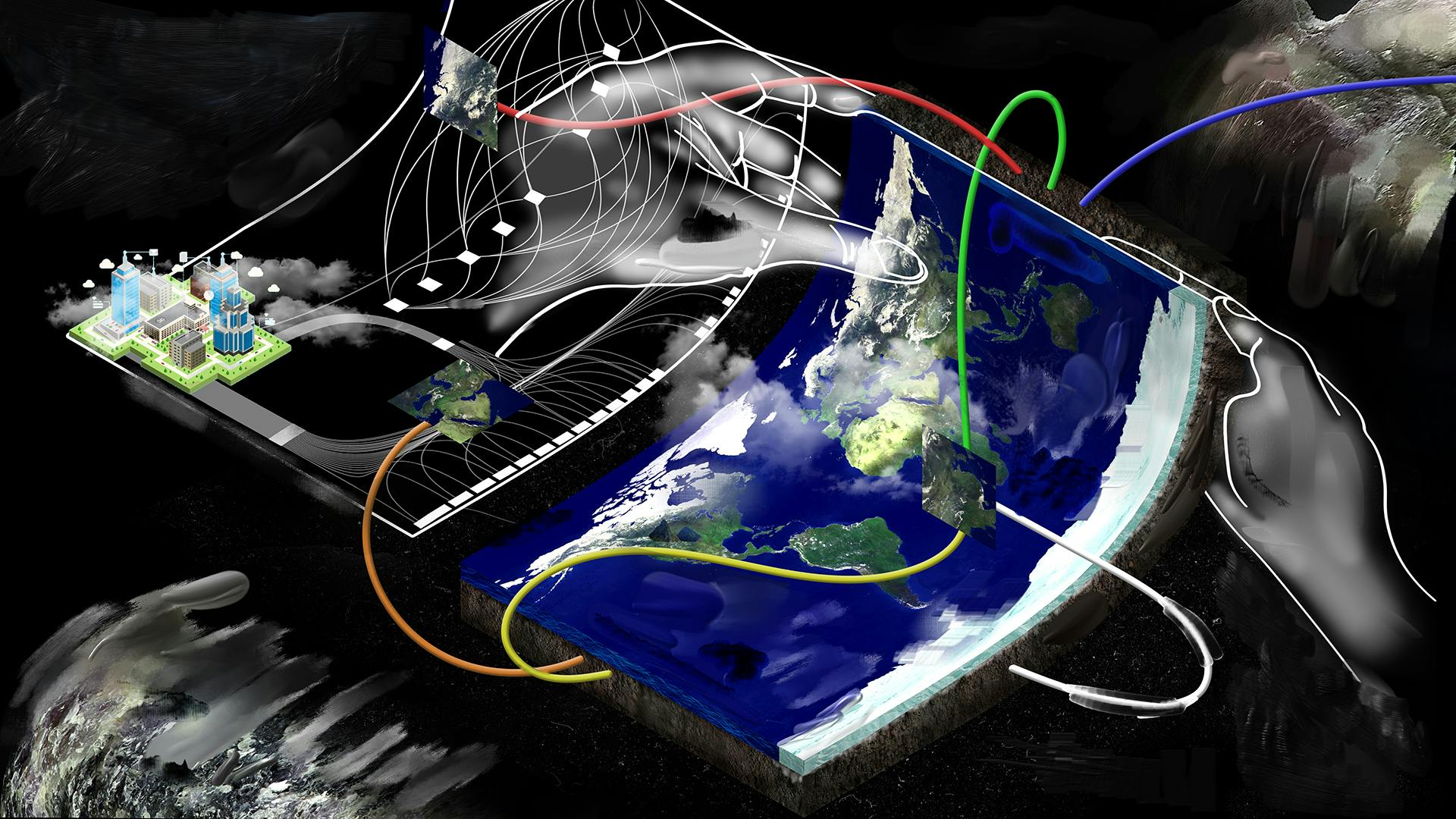

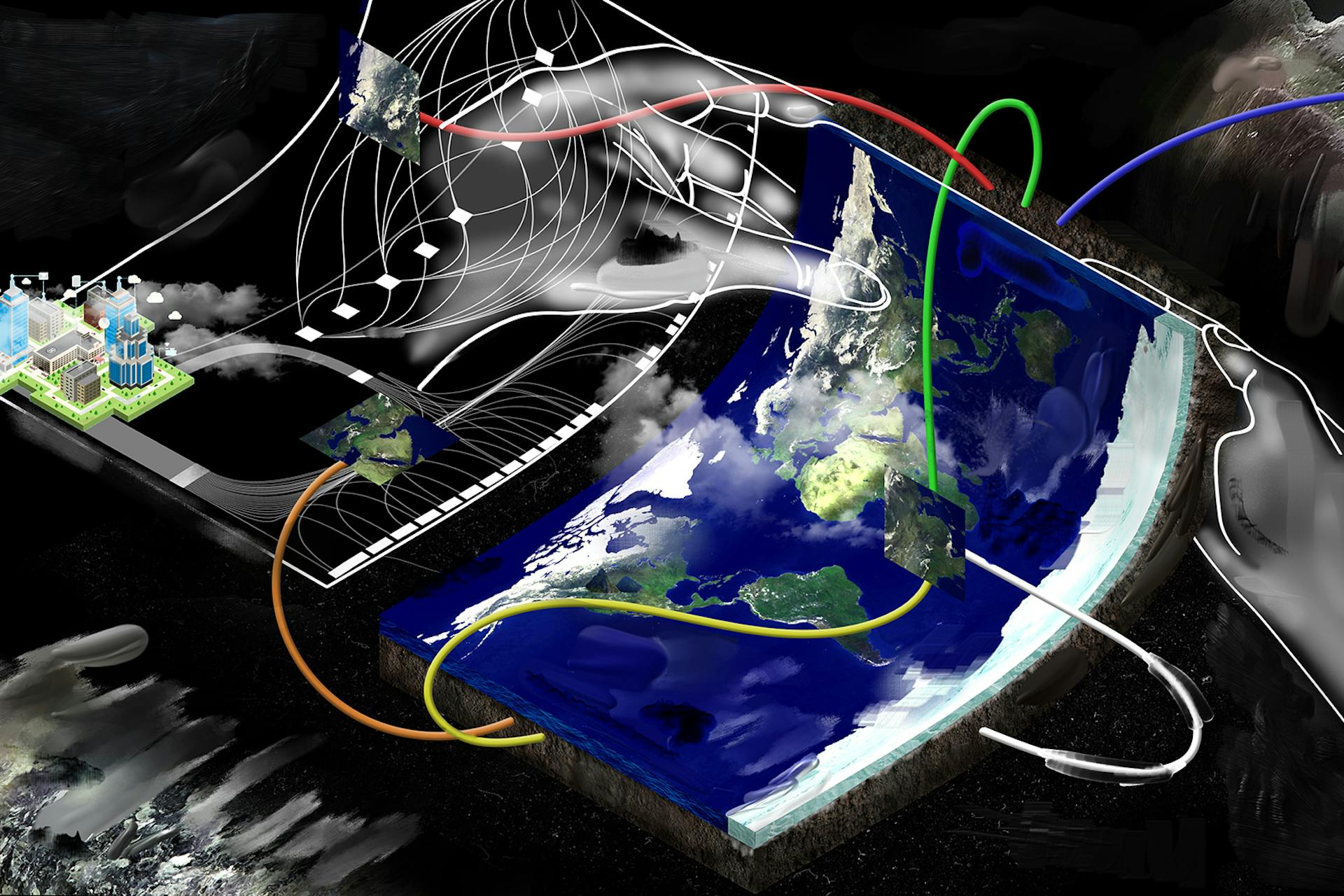

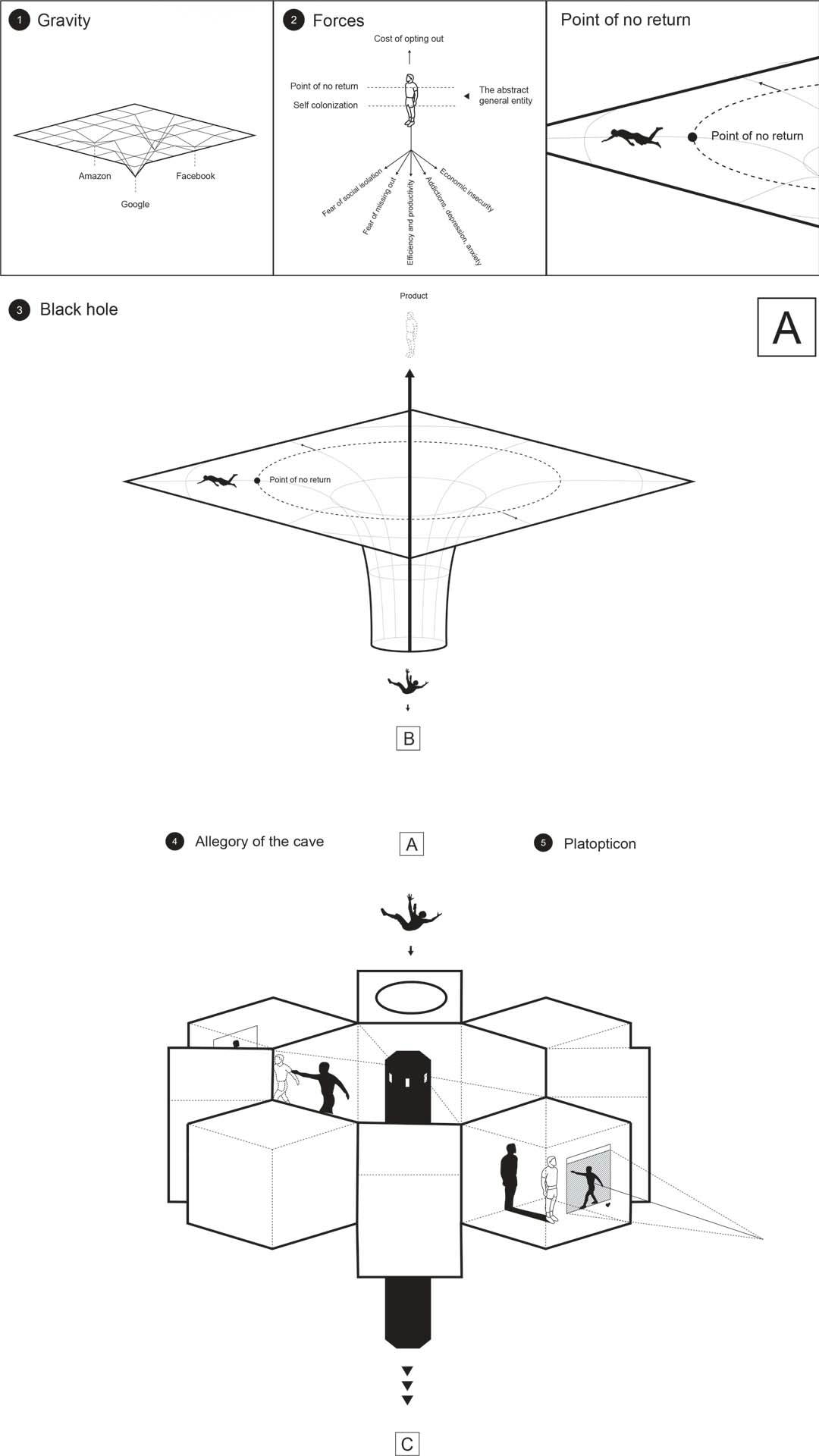

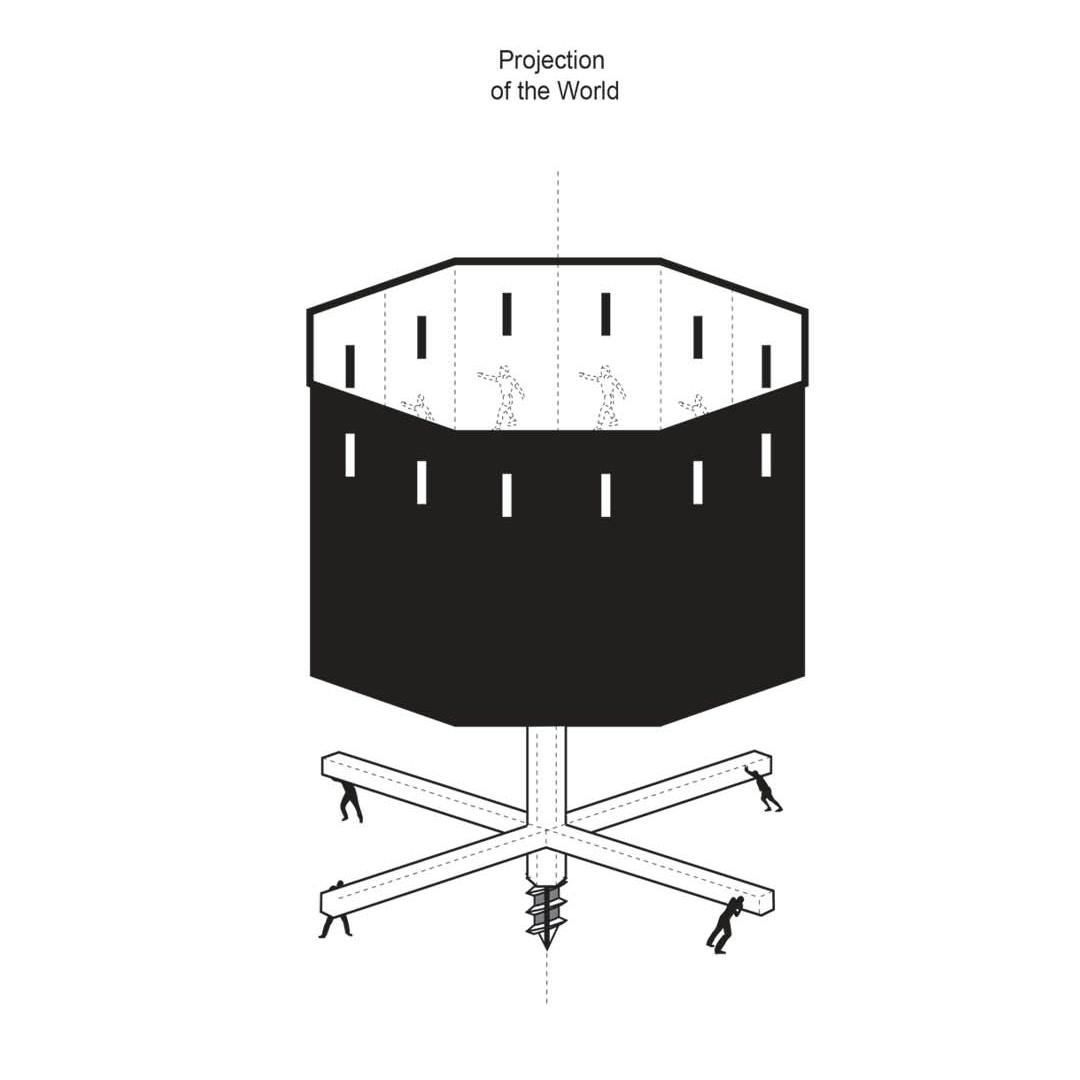

The editorial team decided to call this a “vertical atlas,” as it tries to make visible the different realities that are stacked on top of each other in ways that are inextricable. The Stack (2015) by Benjamin Bratton was the primary inspiration for this book and provides a useful model that helped us investigate the many social, political, cultural and environmental implications of the digital transformation on people and societies .1 These range from the immediate impact on the users of the technological systems to developments on city level to the extraction of the resources that built the digital infrastructures.

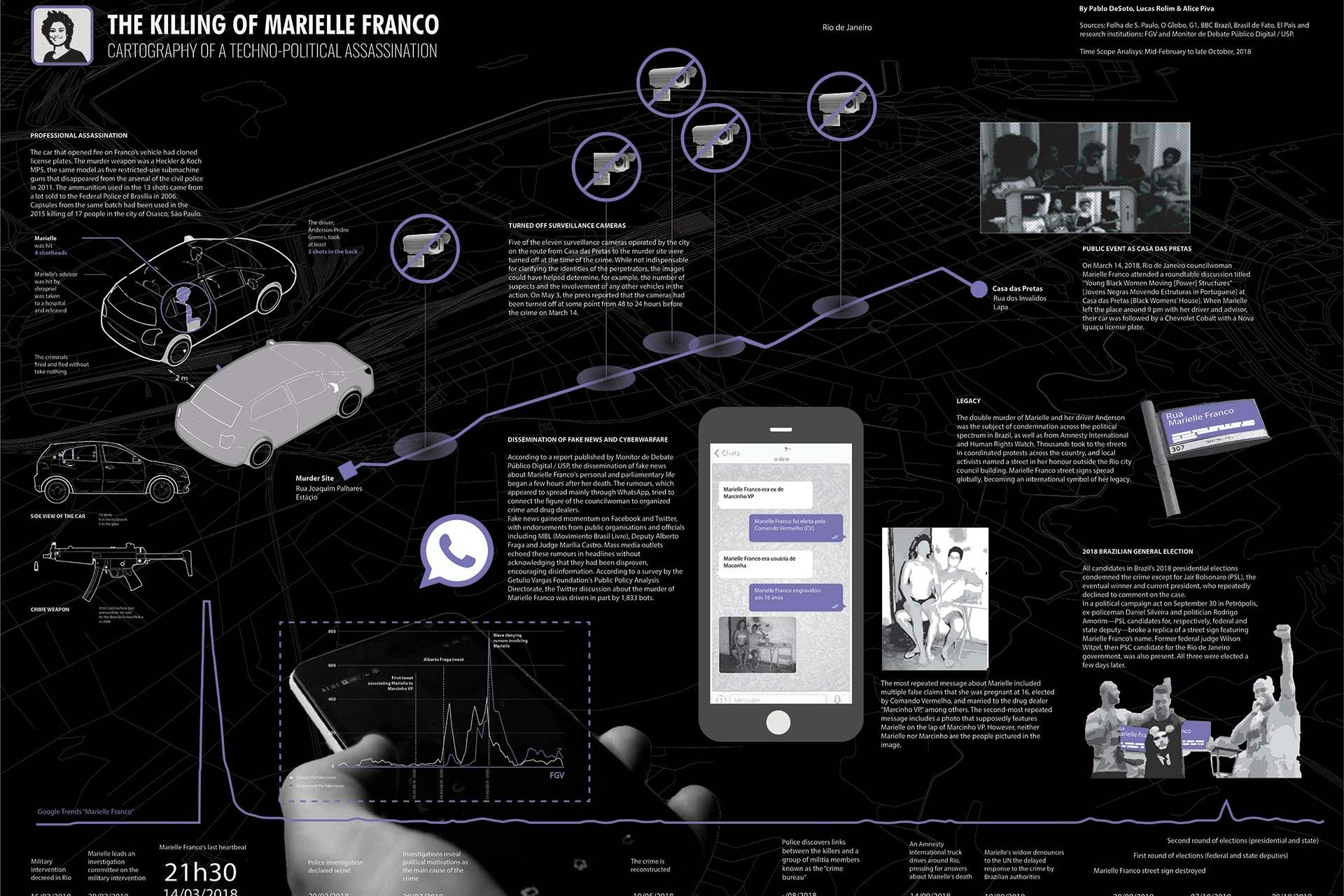

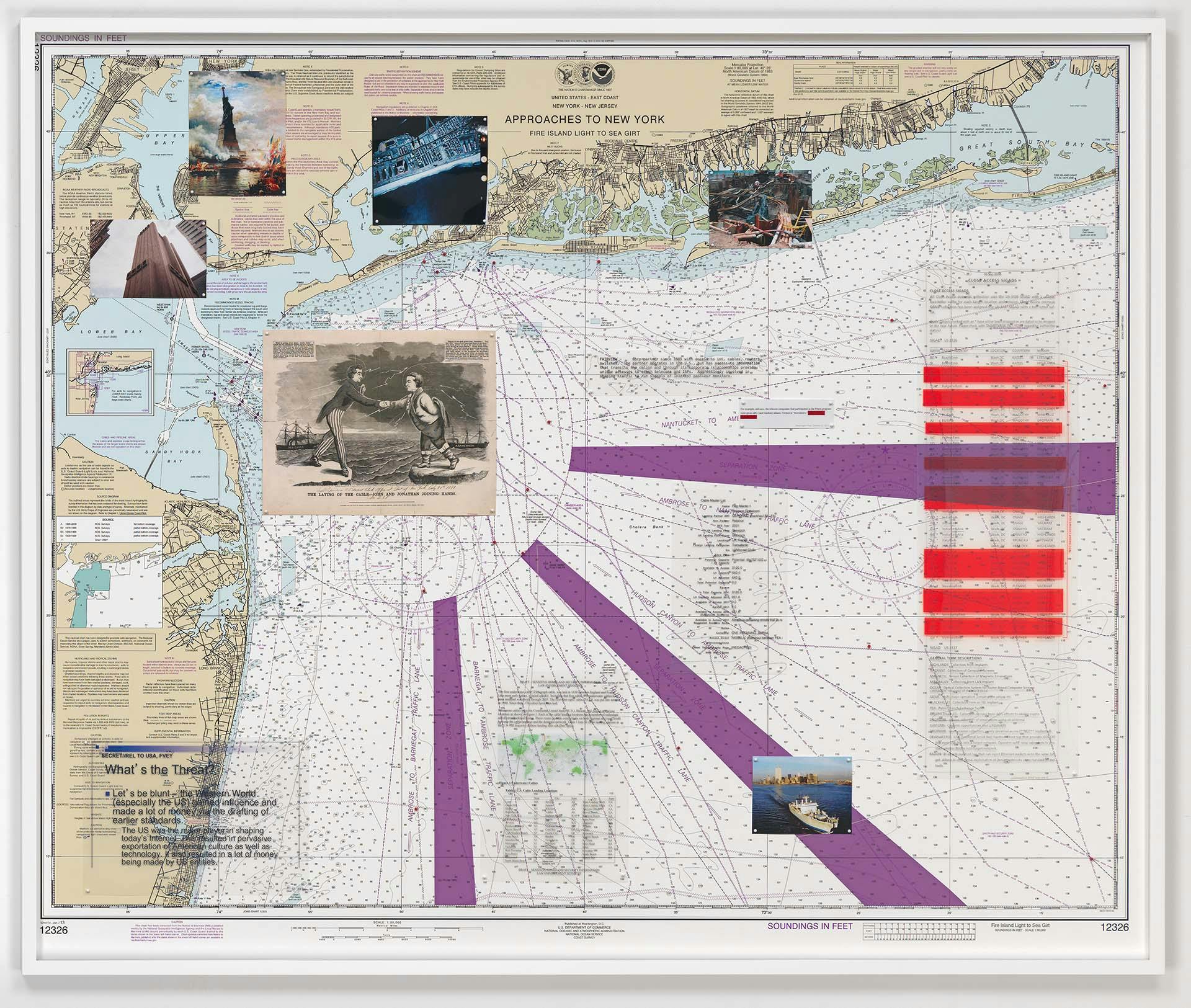

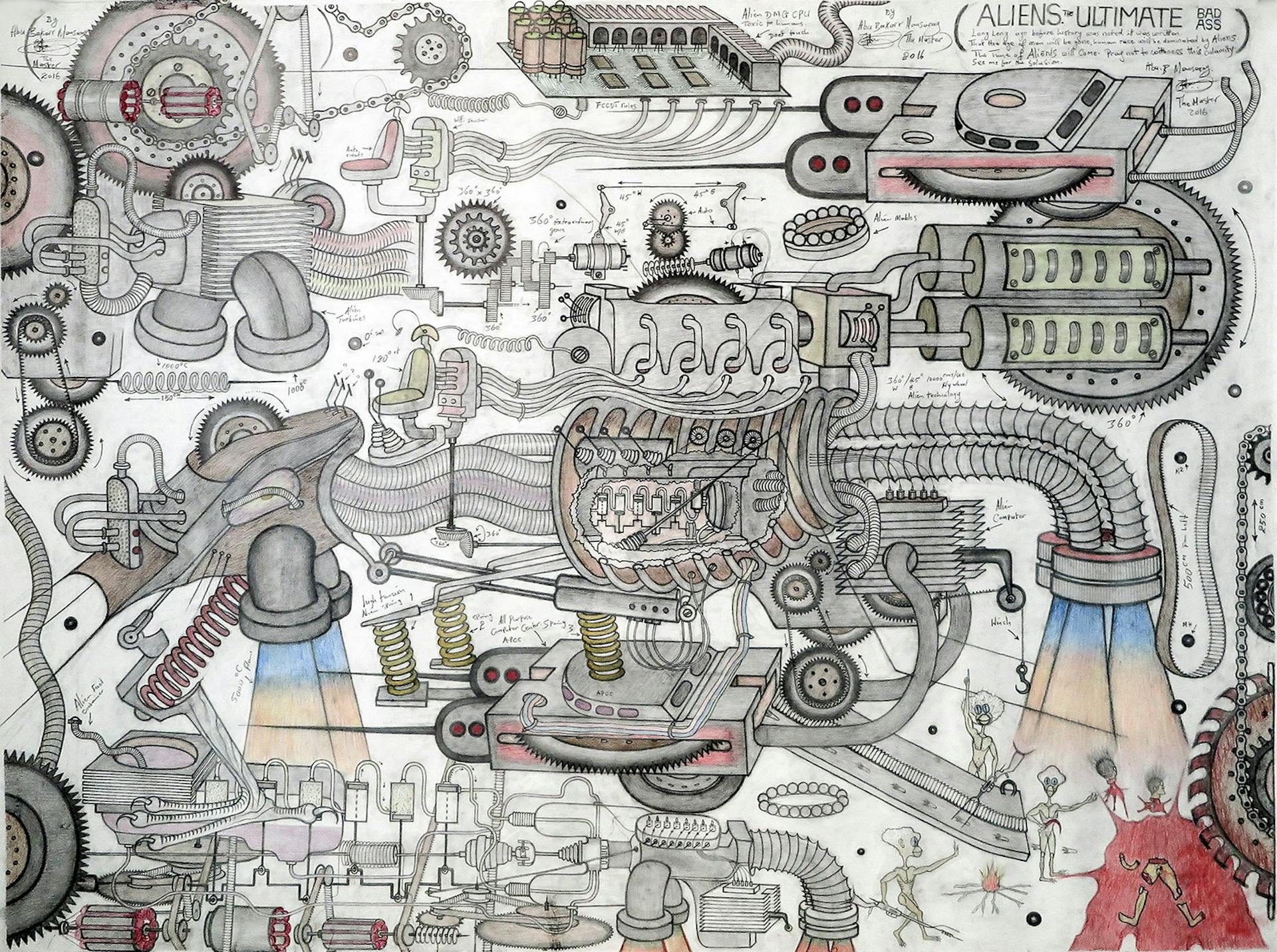

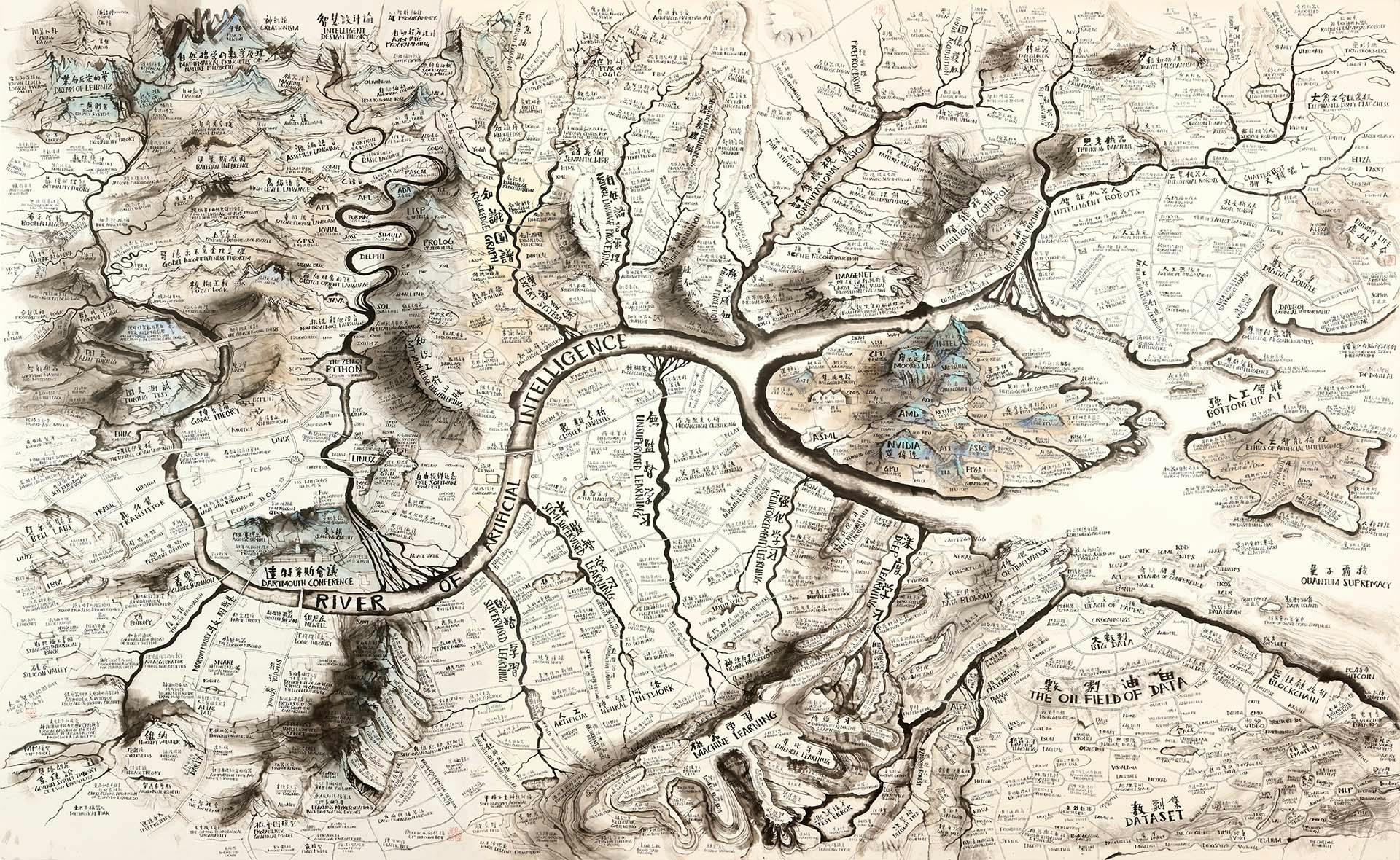

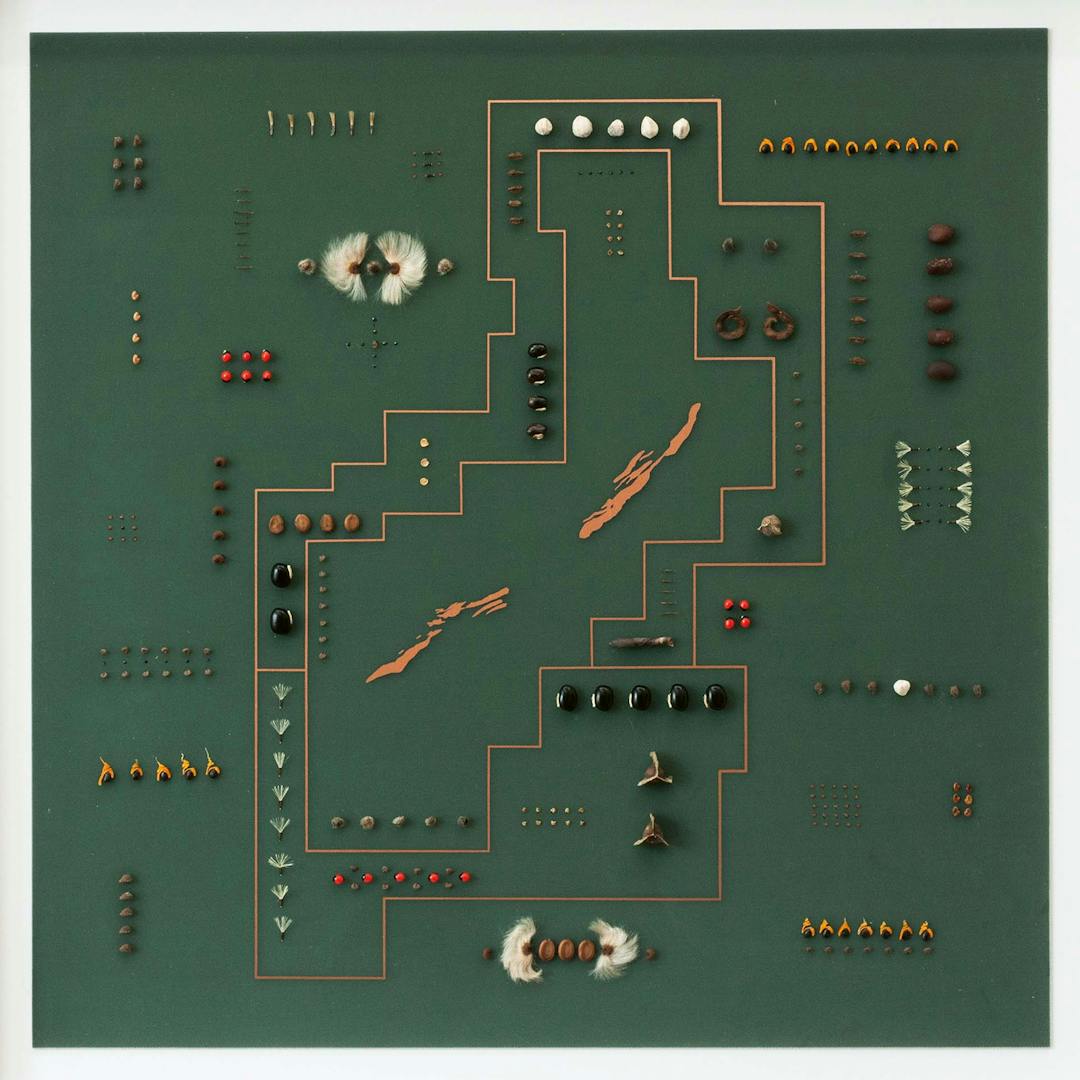

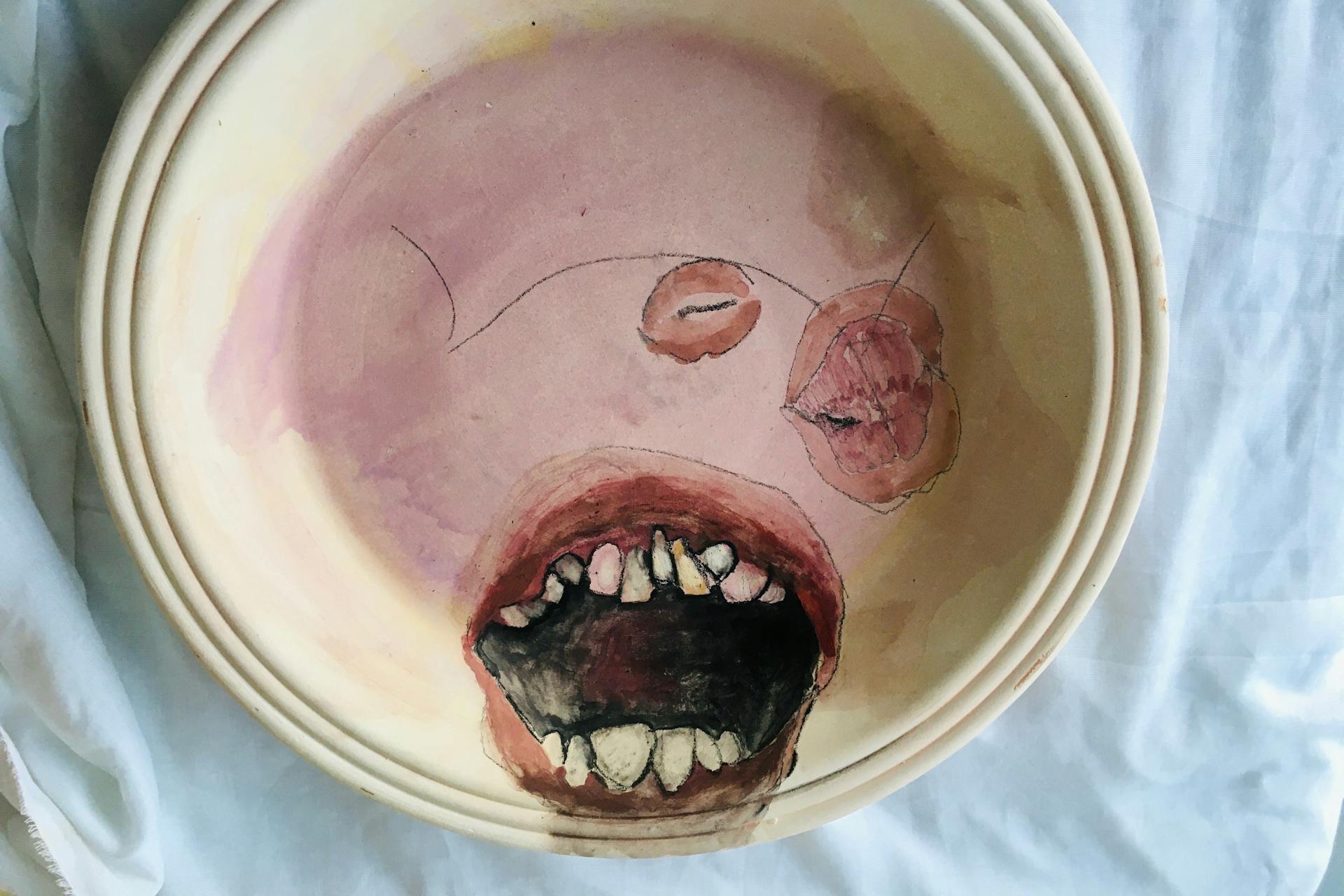

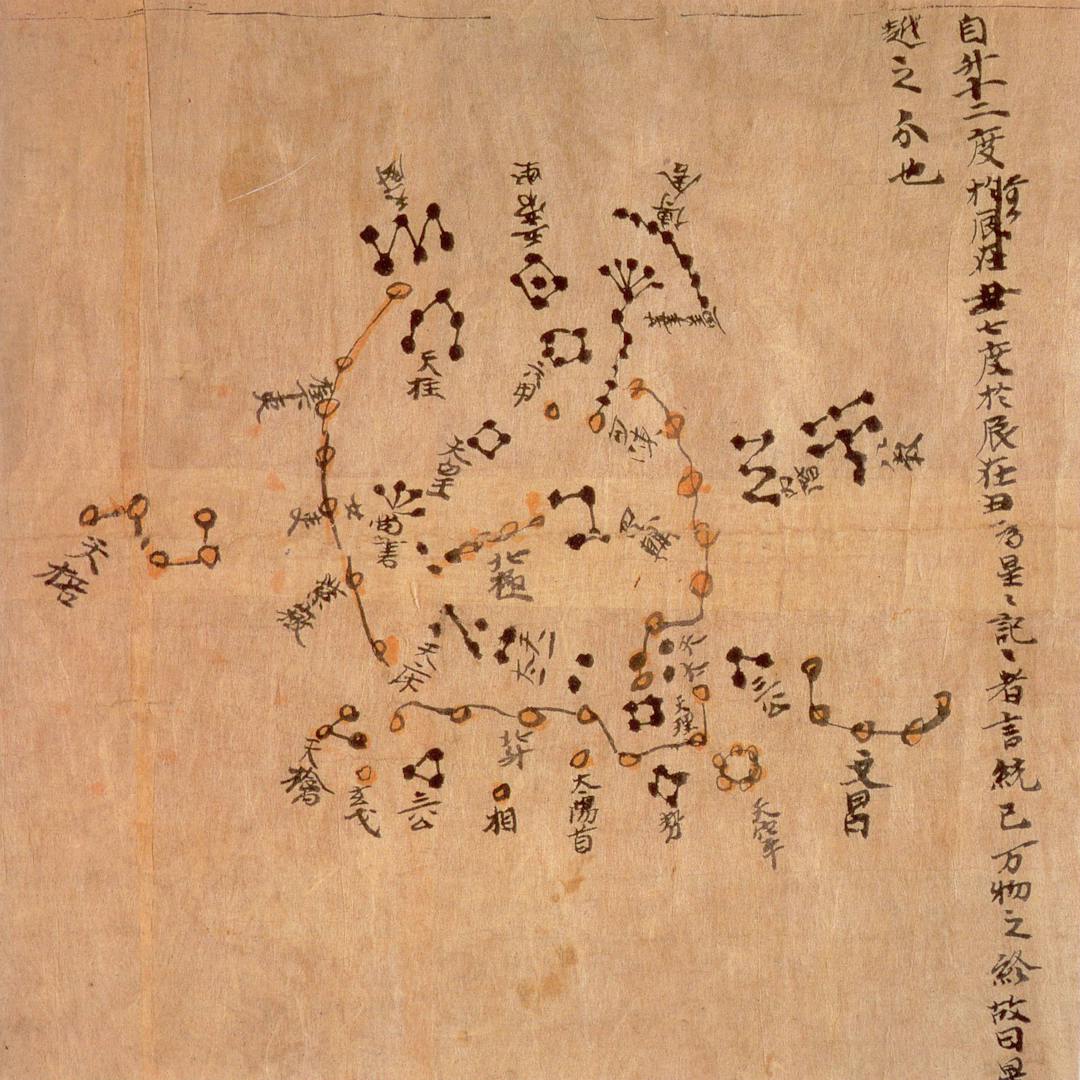

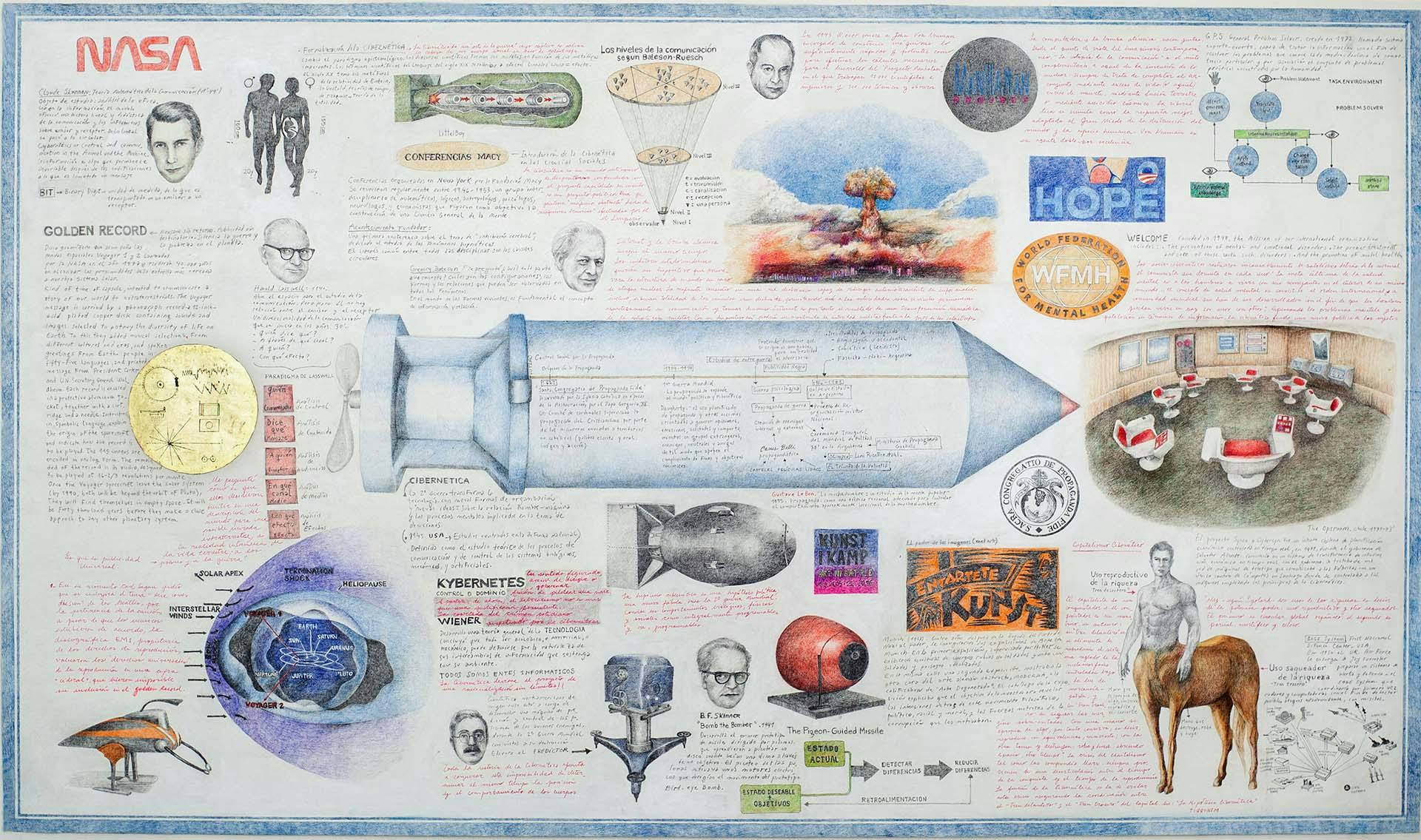

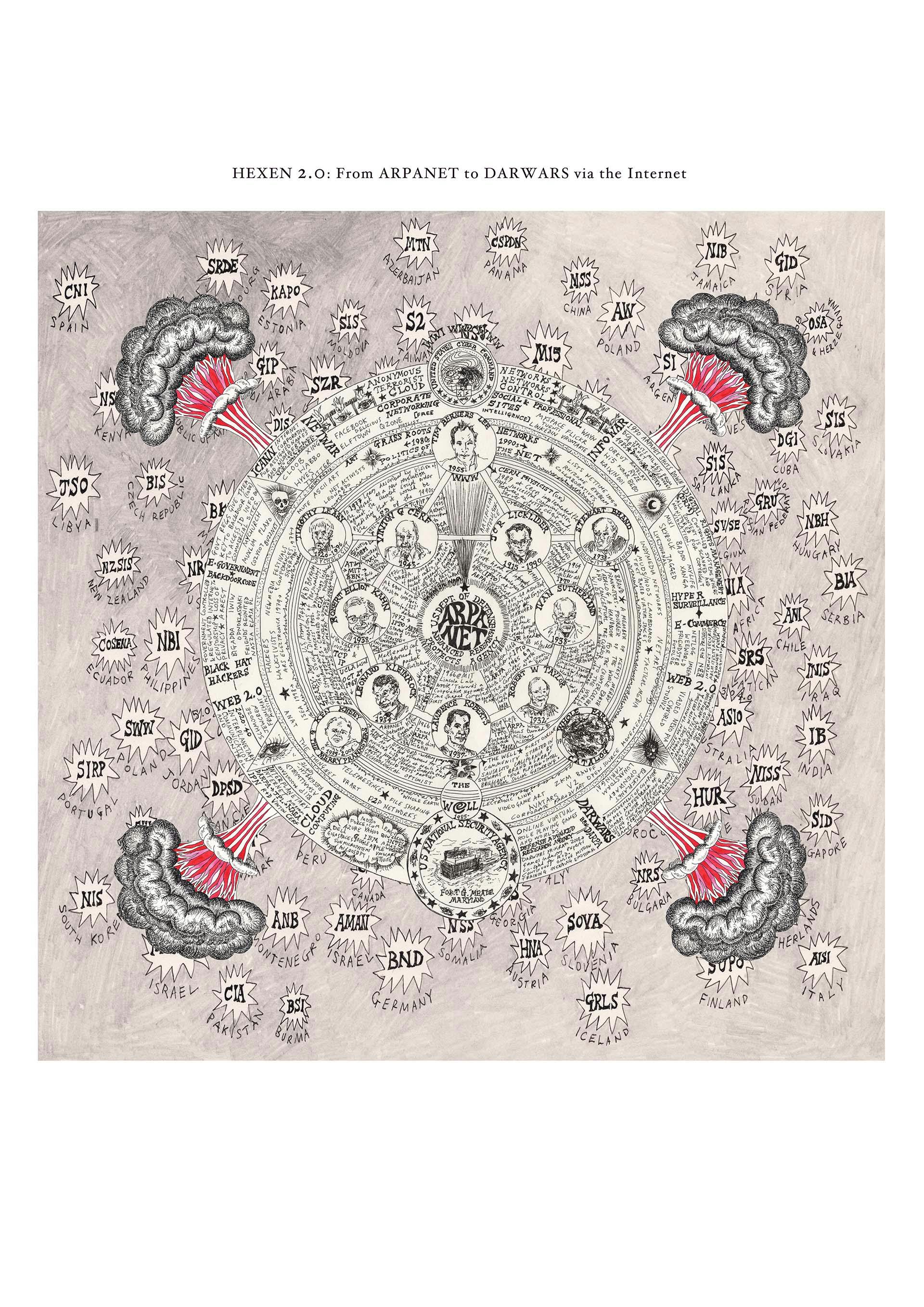

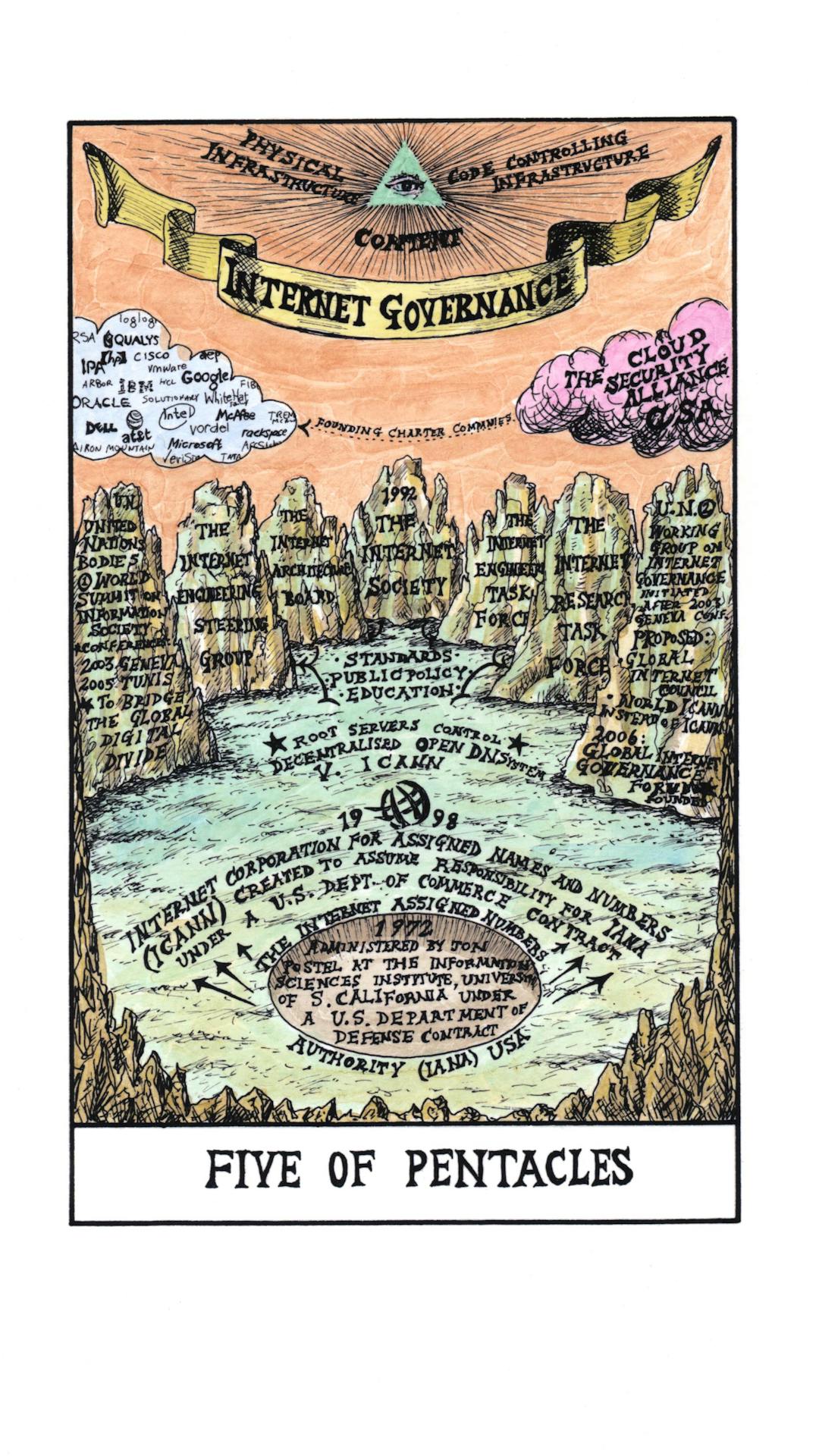

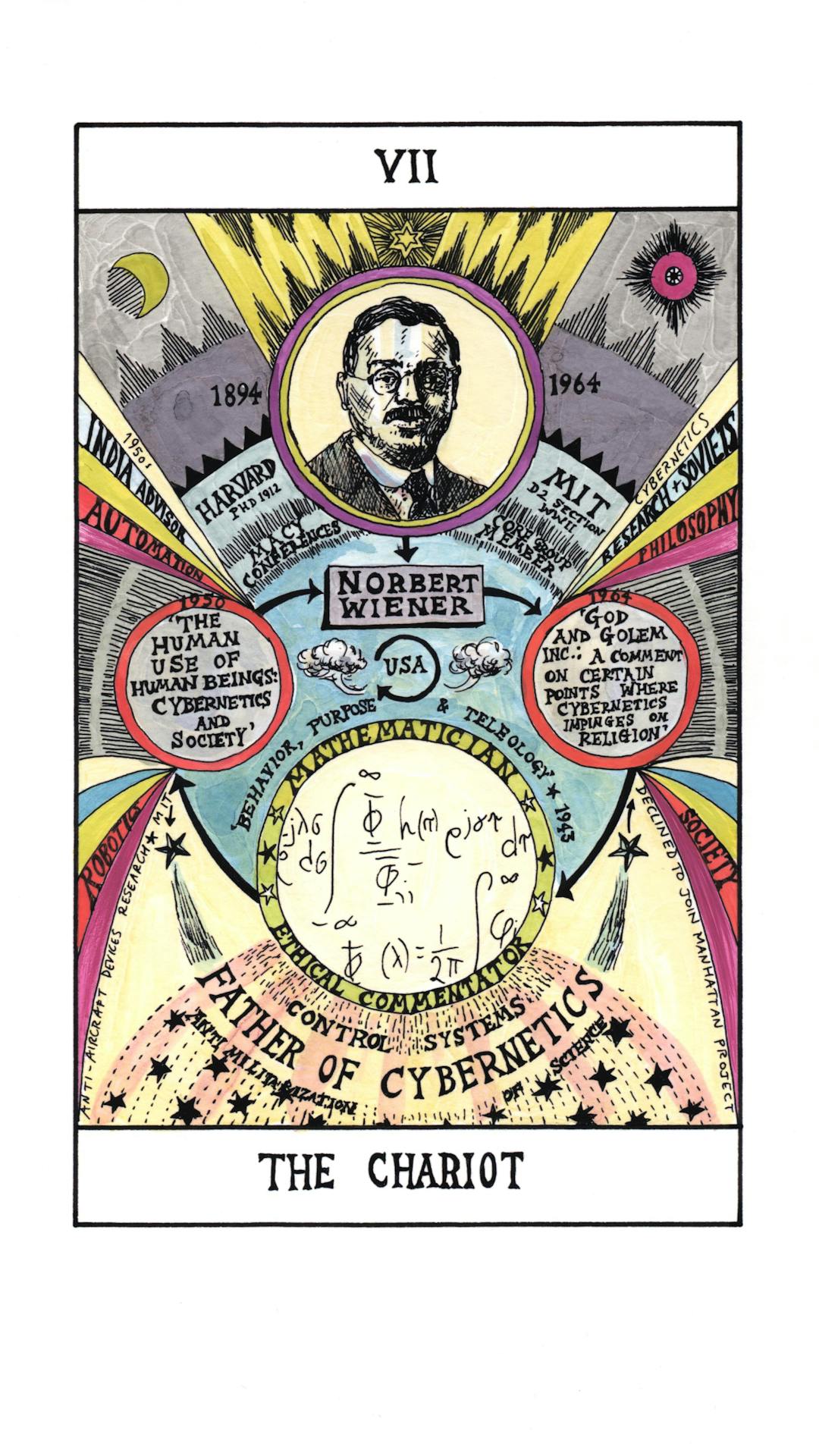

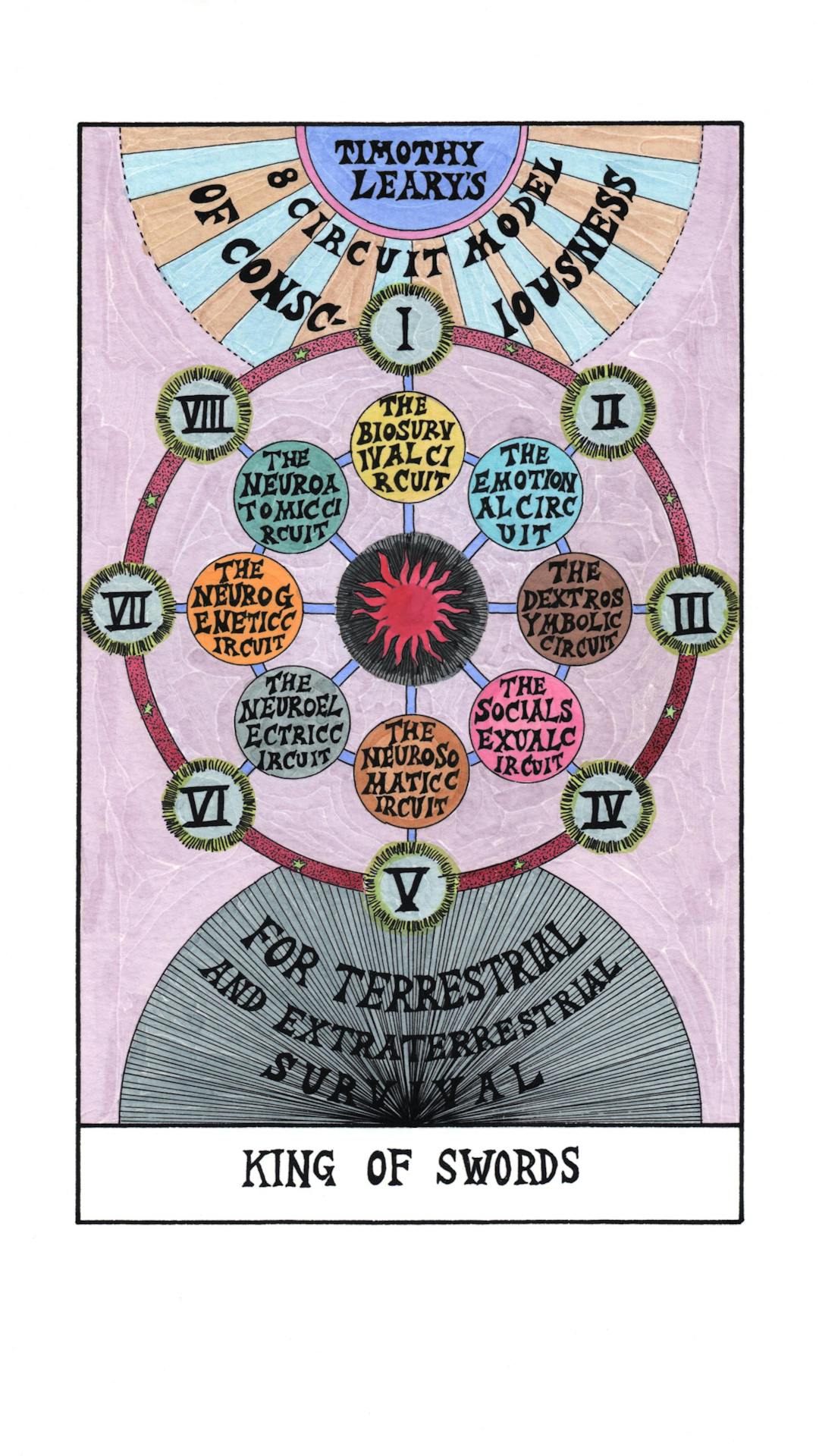

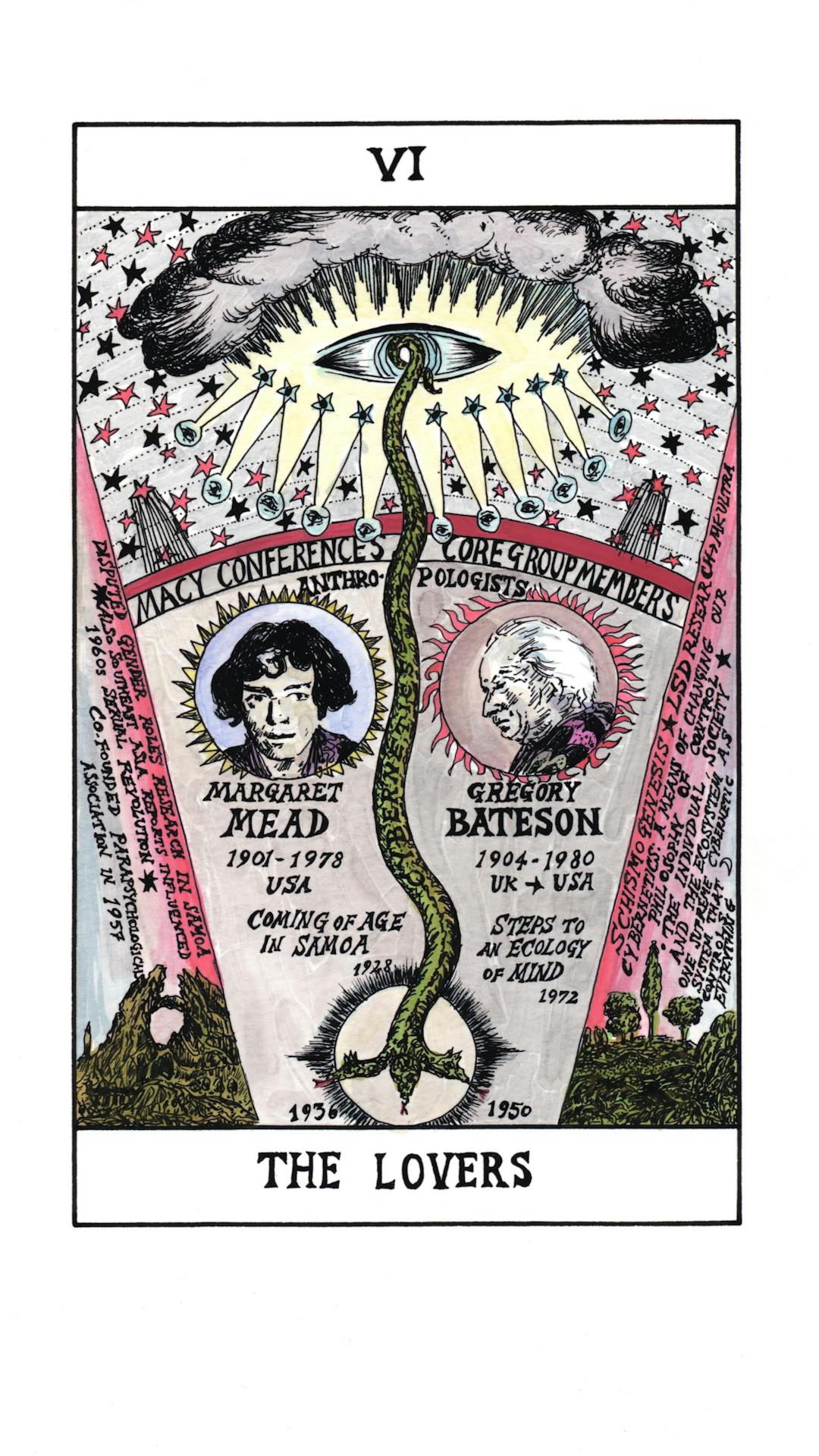

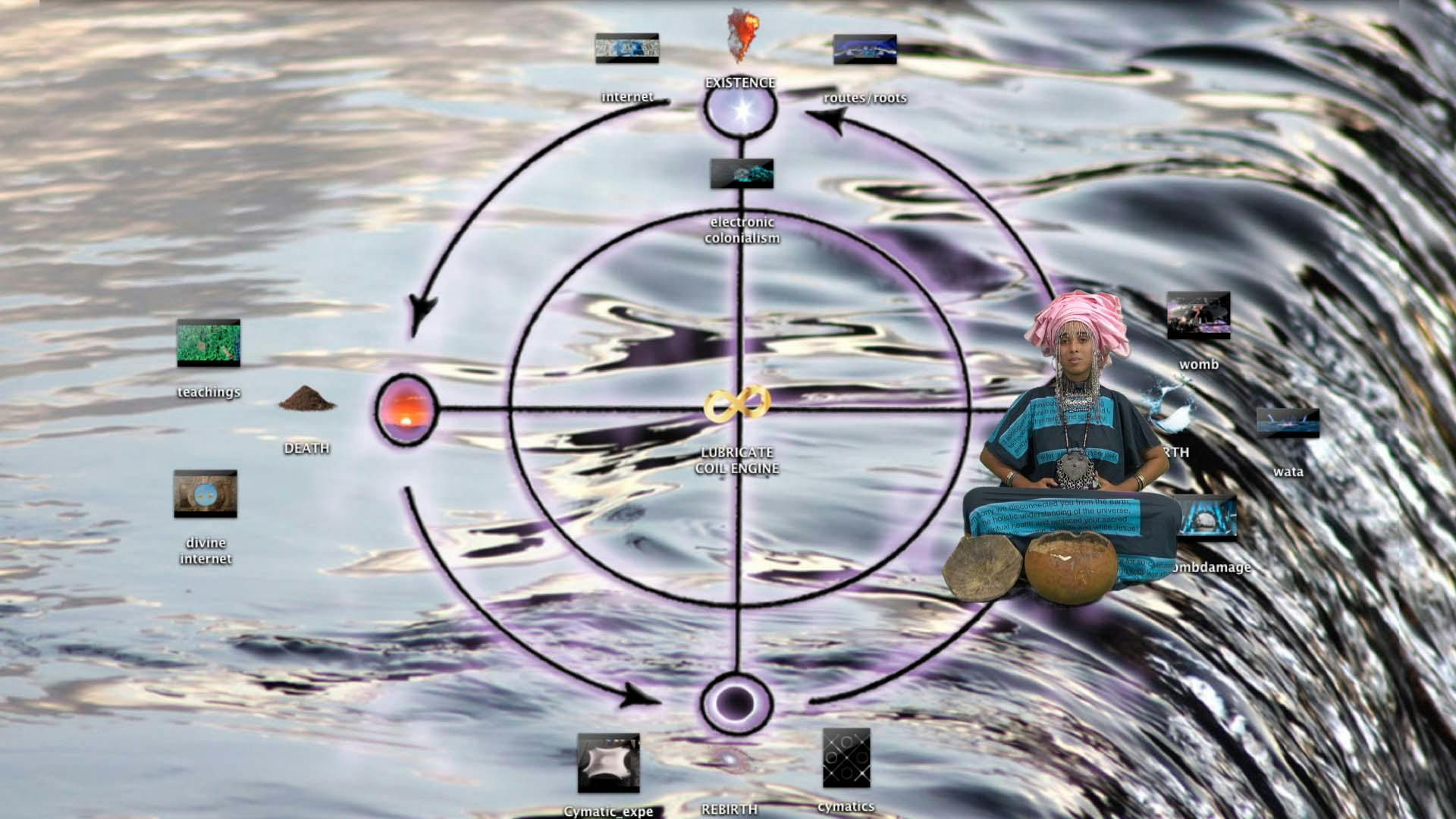

This book is not an atlas in the sense of a collection of colonial maps of the earth, drawn from the center of power, but is rather a tool that enables the comparison, correlation and juxtaposition of very different realities–this is reflected in the variety of forms these maps take: diagrams, interviews, essays or artworks.

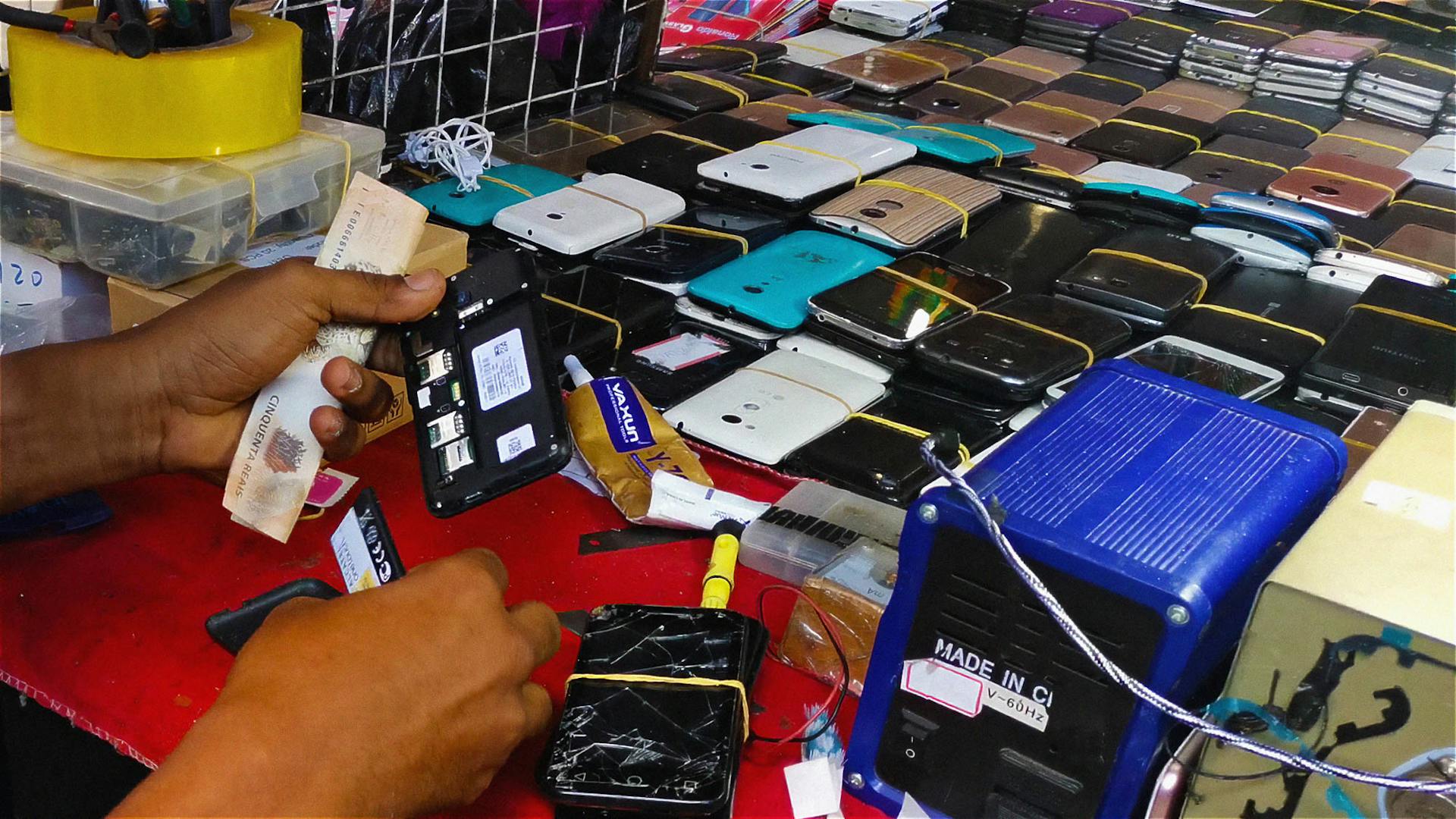

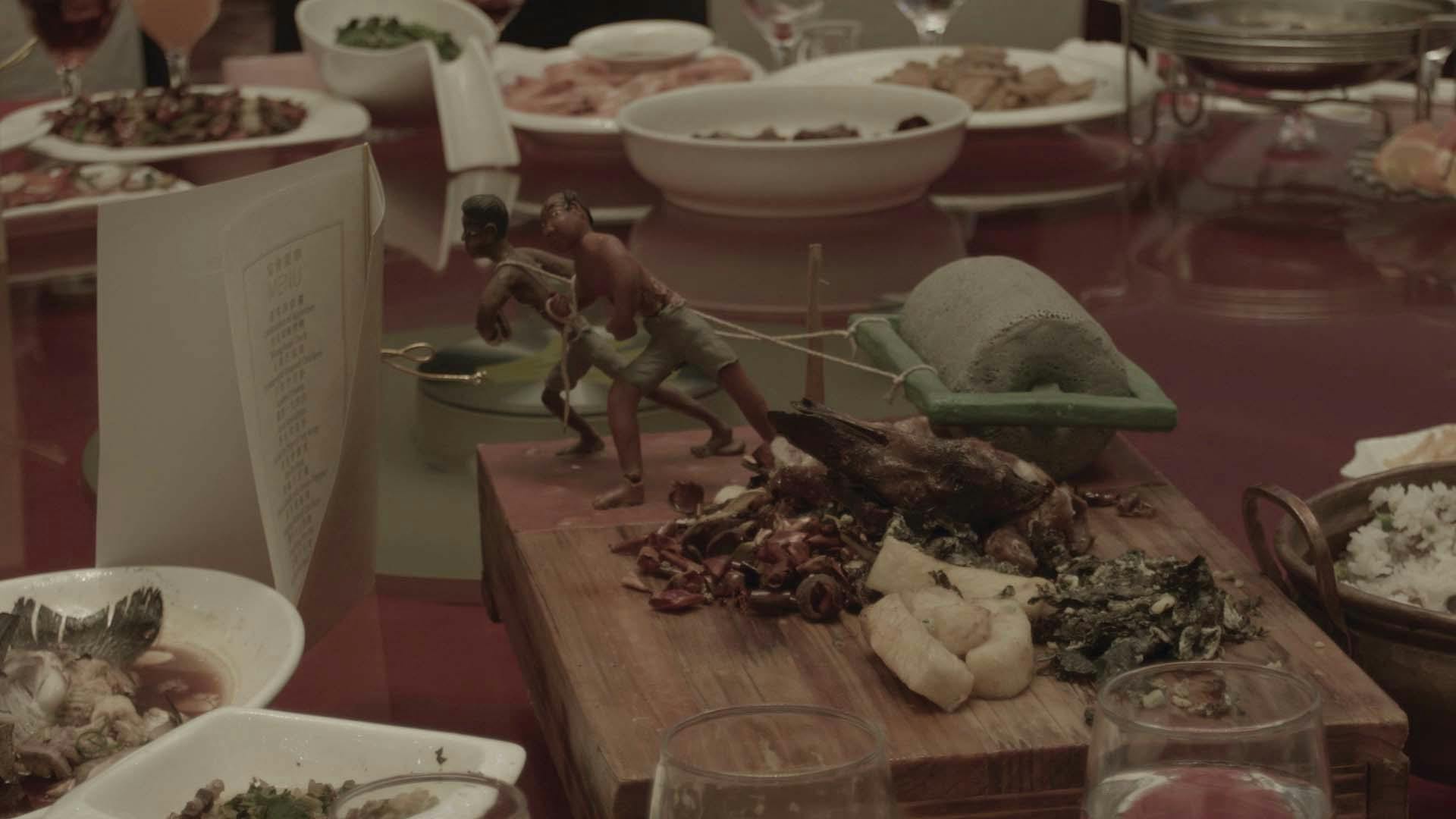

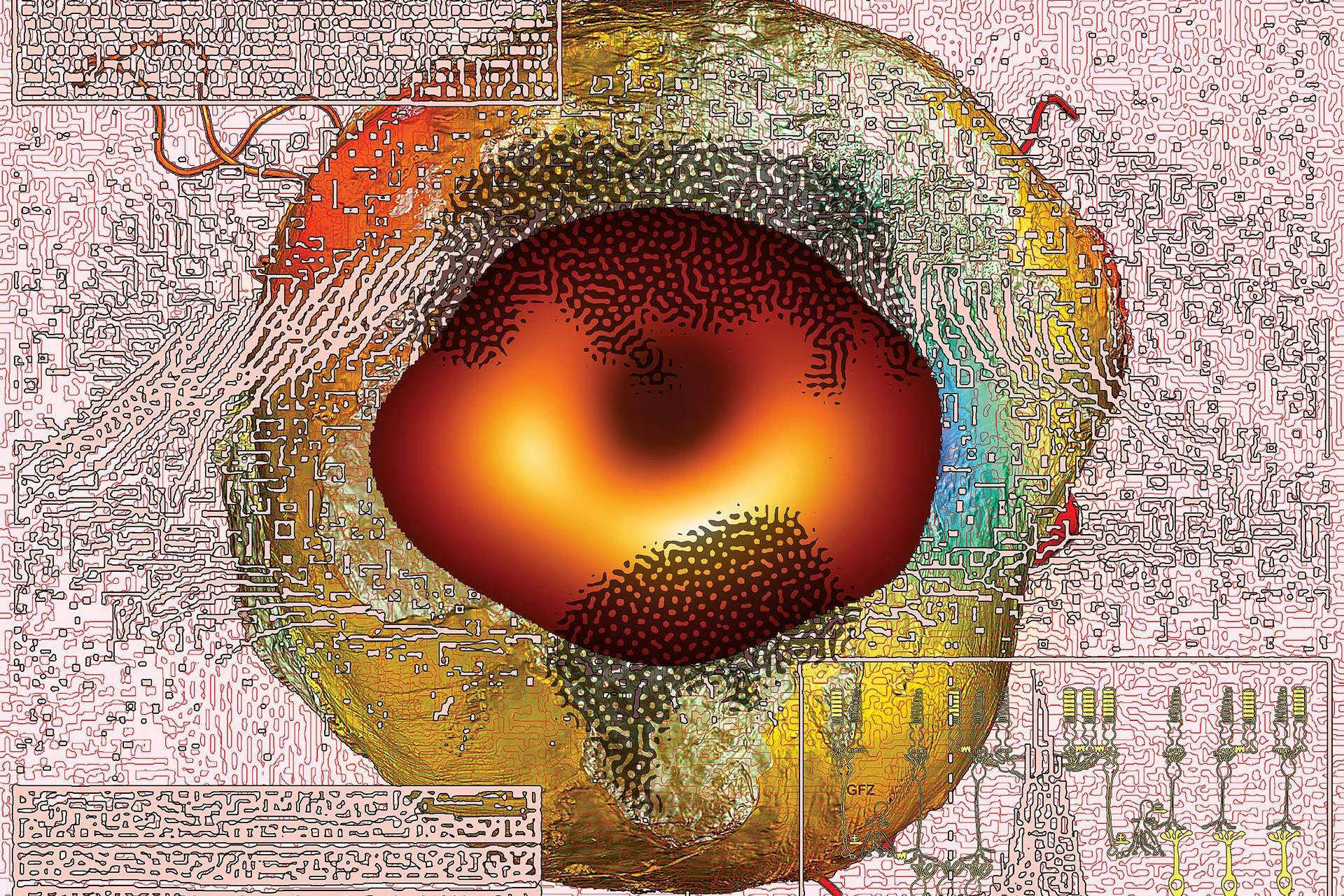

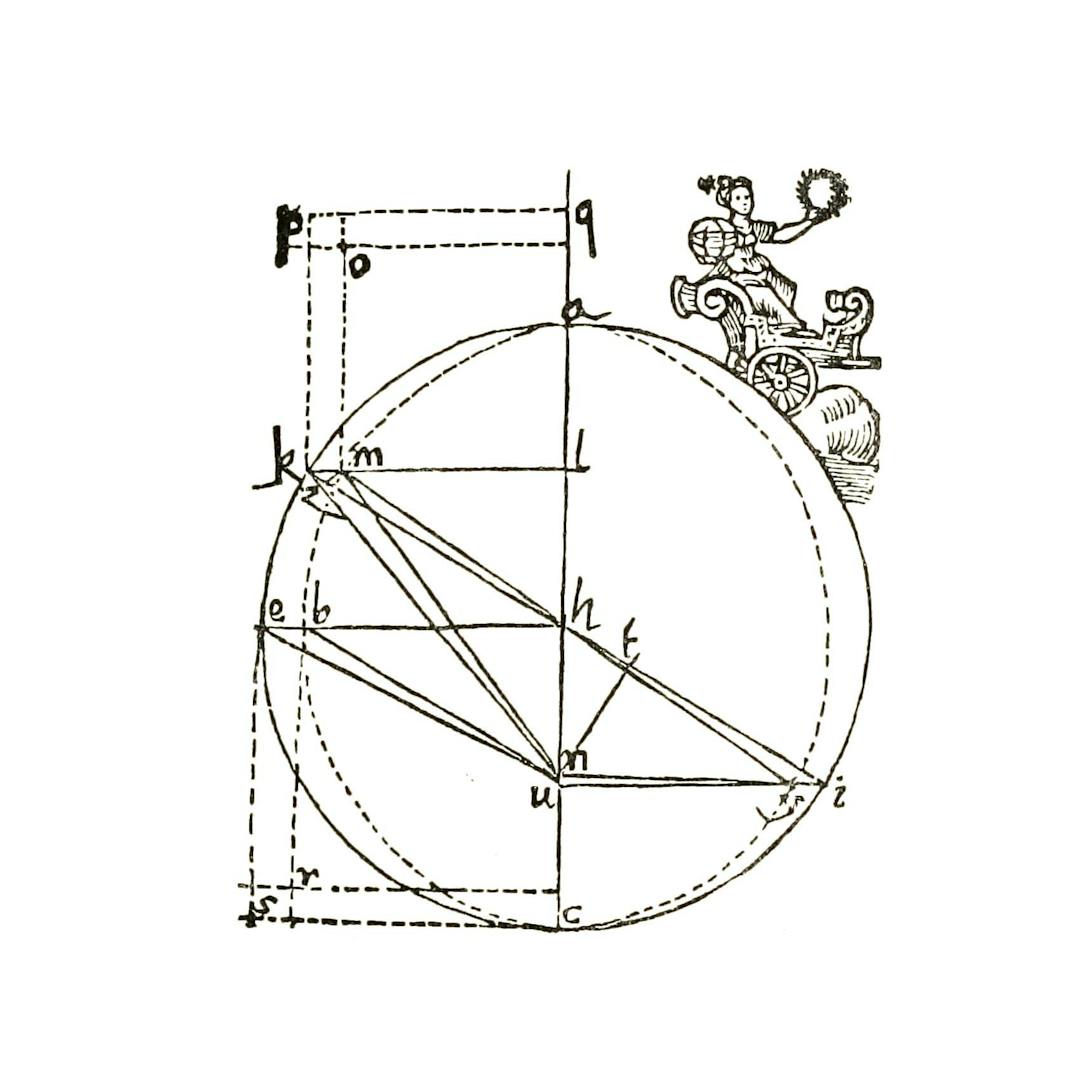

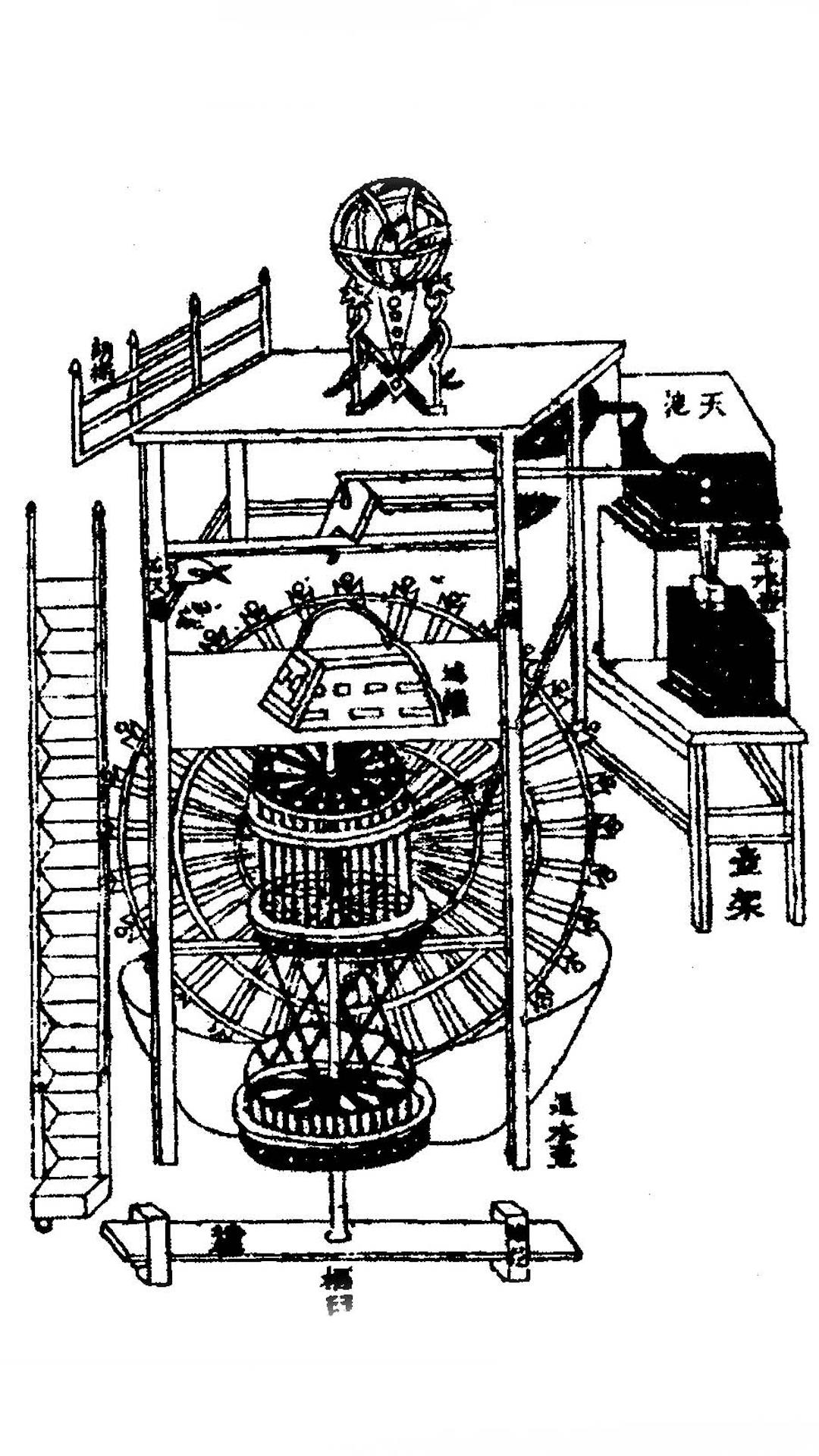

It is not the goal to create a unified presentation of the world, but rather the opposite: to question the smooth globalized ‘mono-technological’ sphere that is so often promoted by Big Tech as being our shared reality and singular future. Yuk Hui invented the concepts of cosmotechnics and technodiversity to encapsulate a multitude of deeply different techno-cultural experiences, subsumed by and entangled in digital transformations. Going beyond the mere proliferation of technological gadgets and systems, technodiversity involves rediscovering forgotten techniques as well as new ways of dealing with technology based on different purposes and ways of experiencing the world.(2) The exciting diversity of research journeys in this book show us not only the multiplicity of technological realities around the world but also invites us to imagine our digital future in new ways.

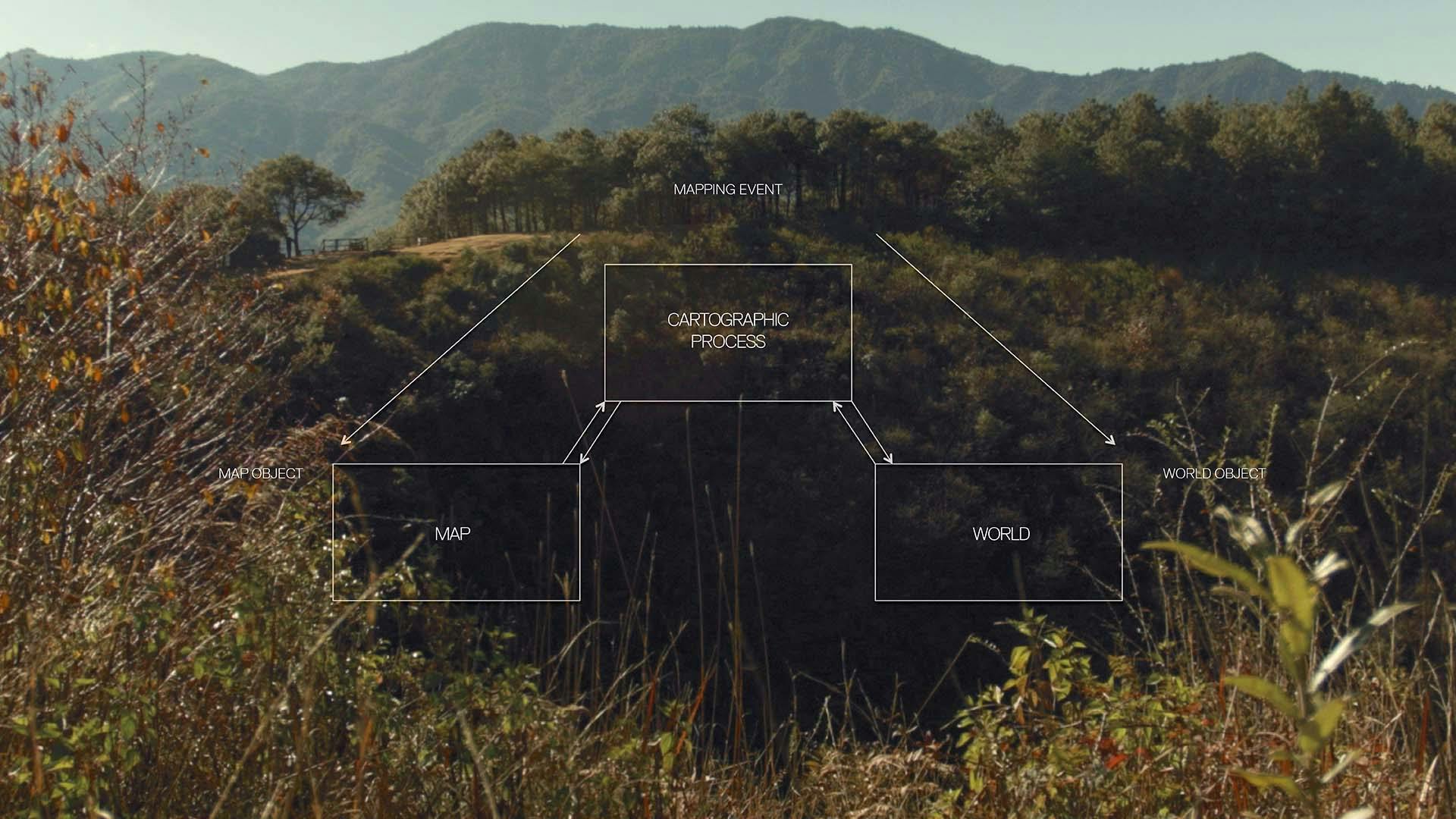

How to map the digital realities?

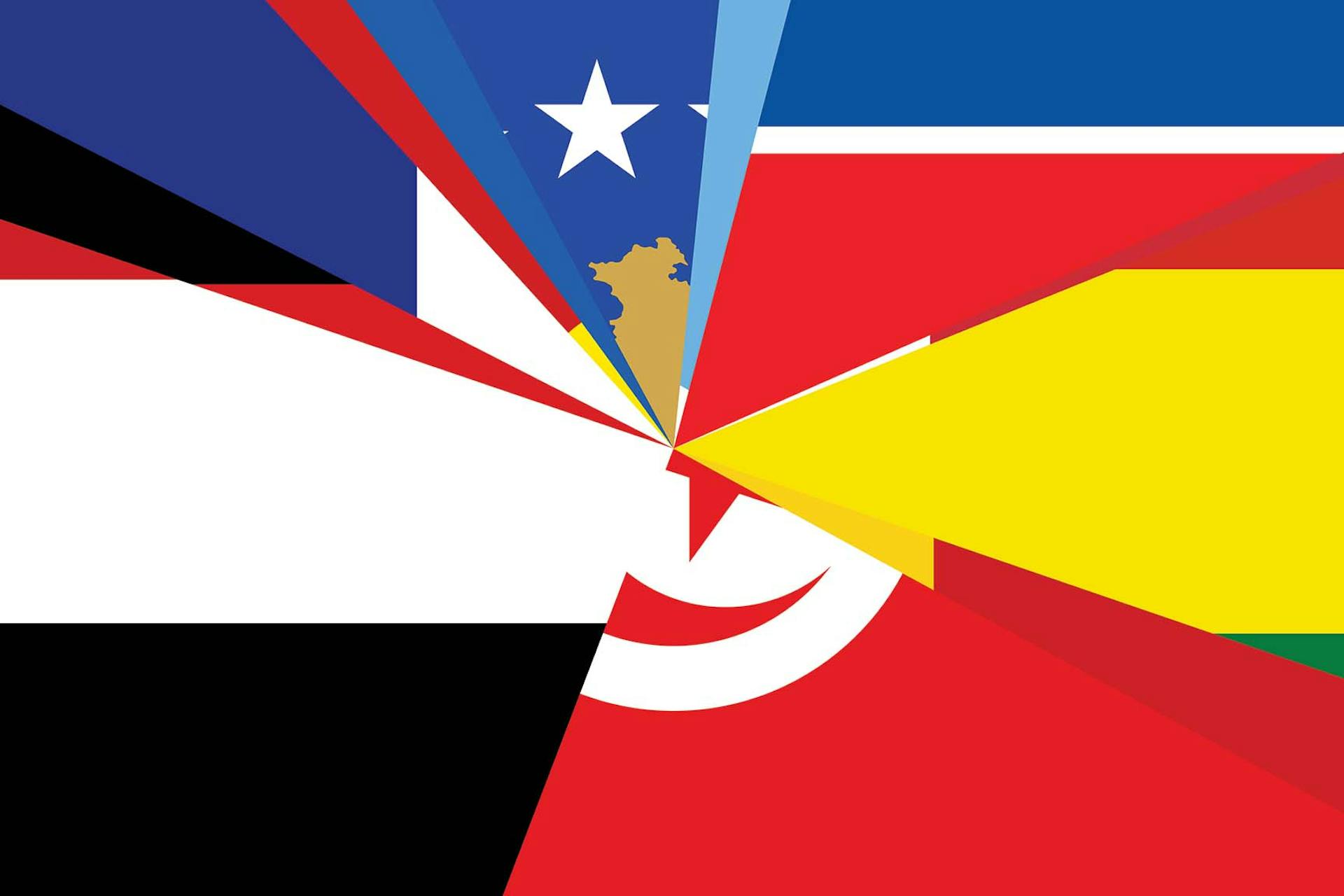

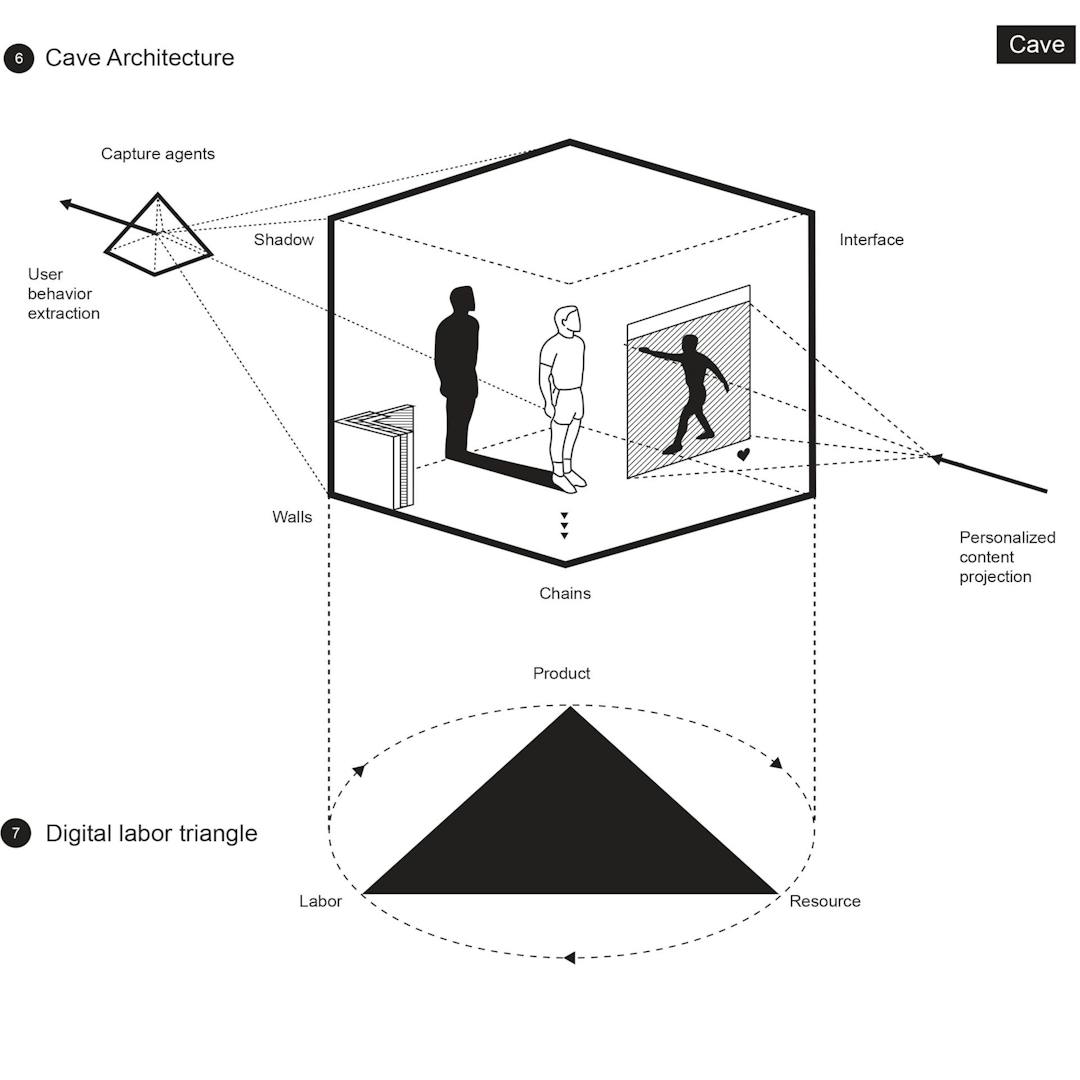

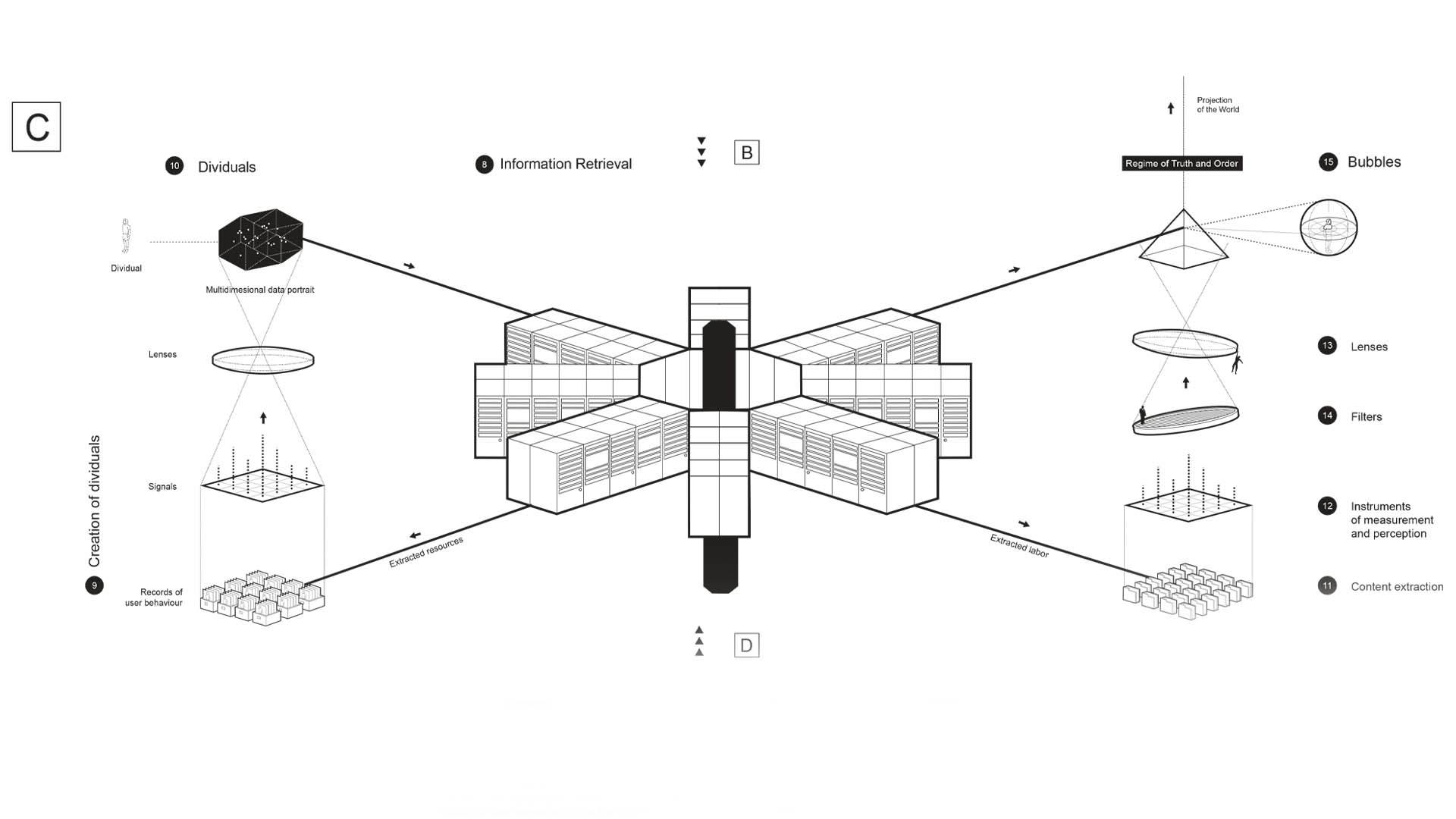

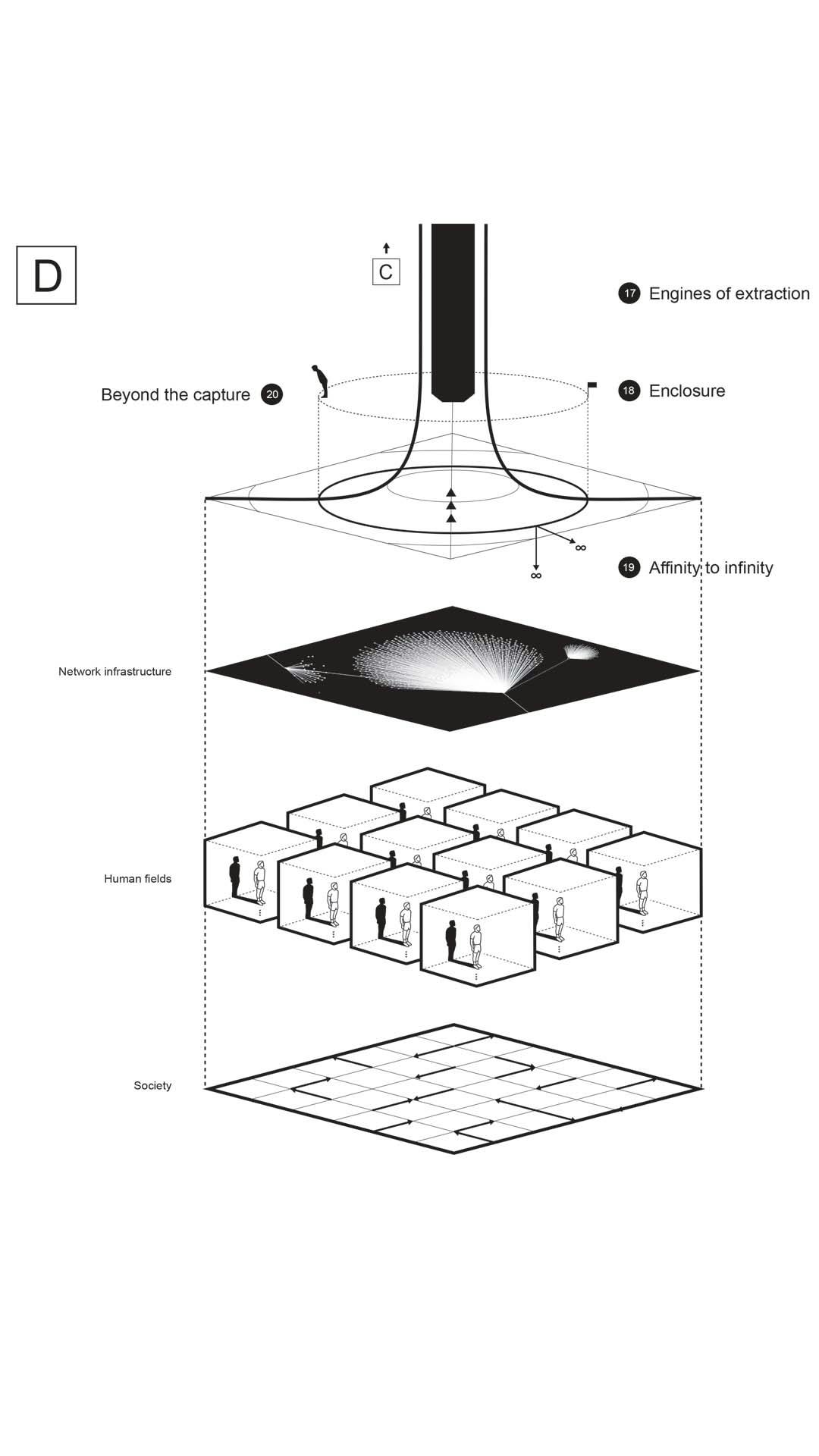

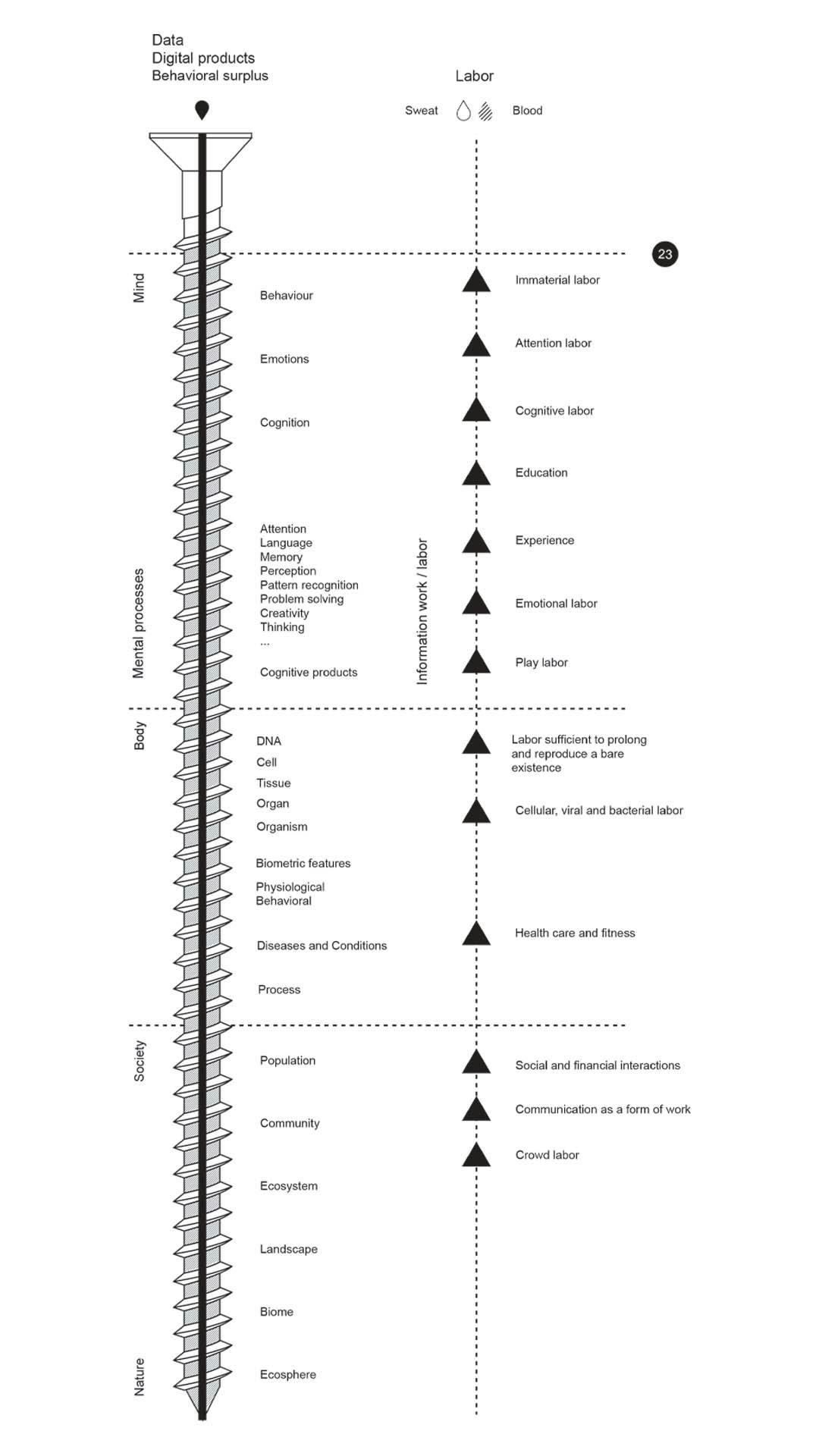

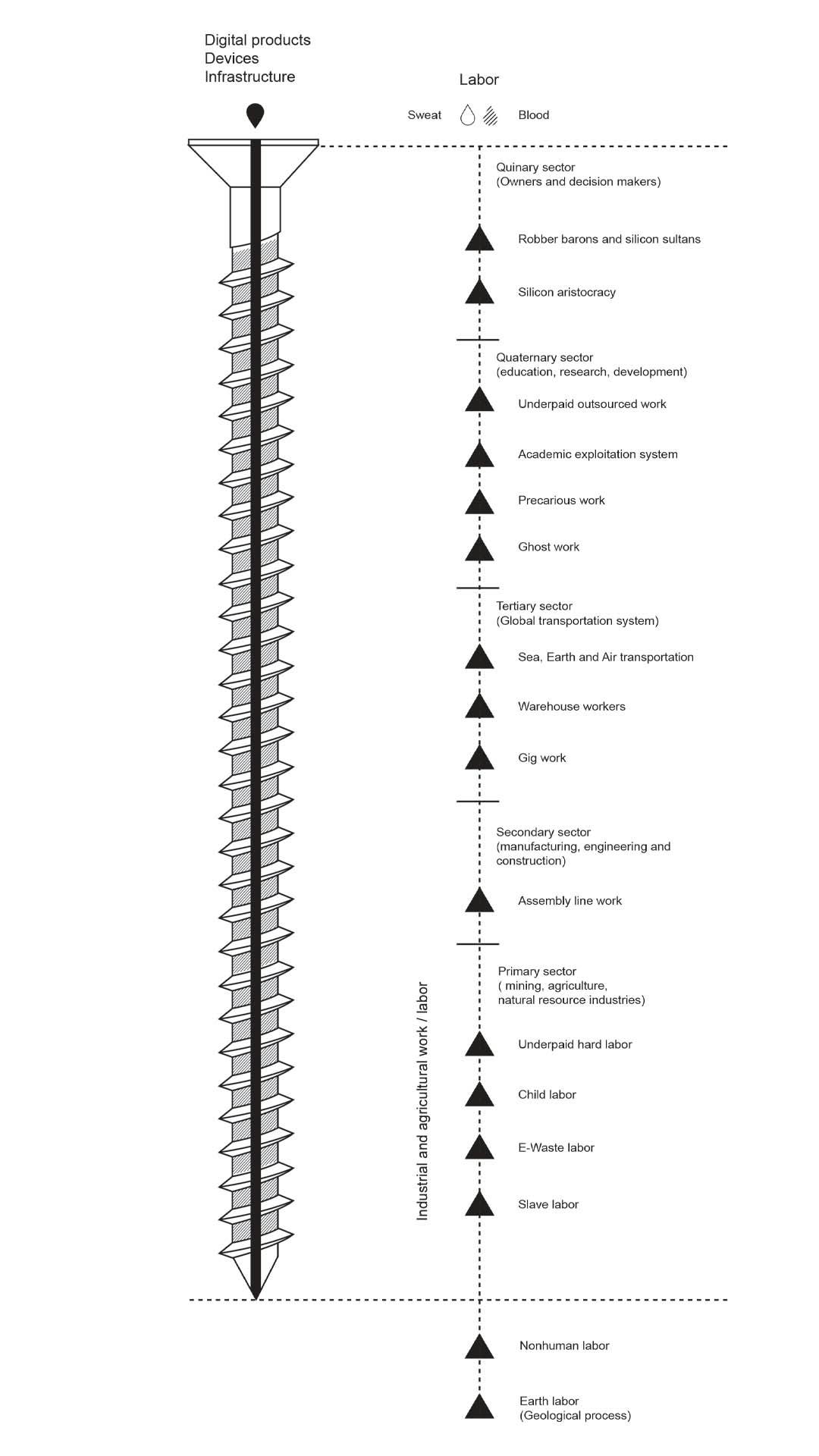

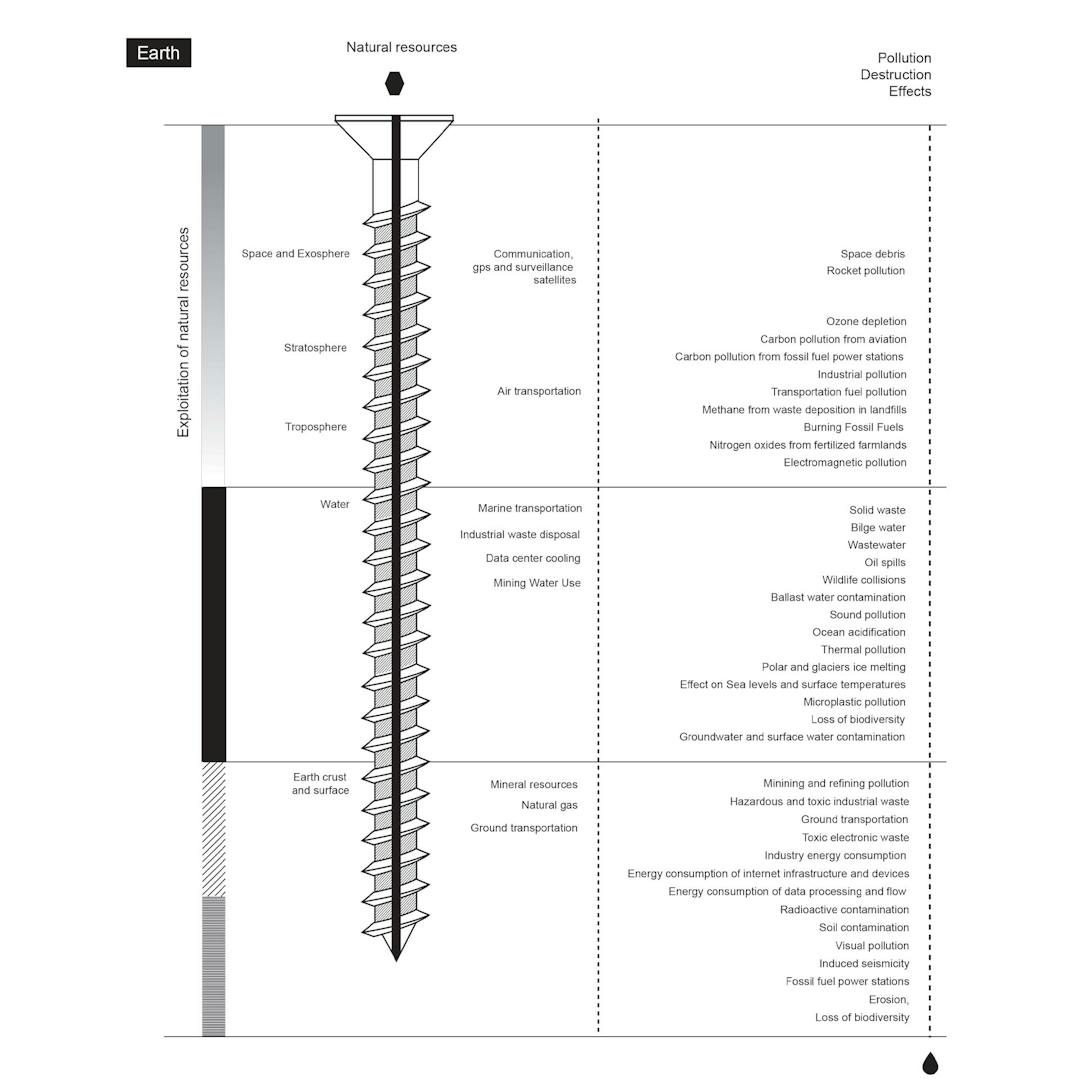

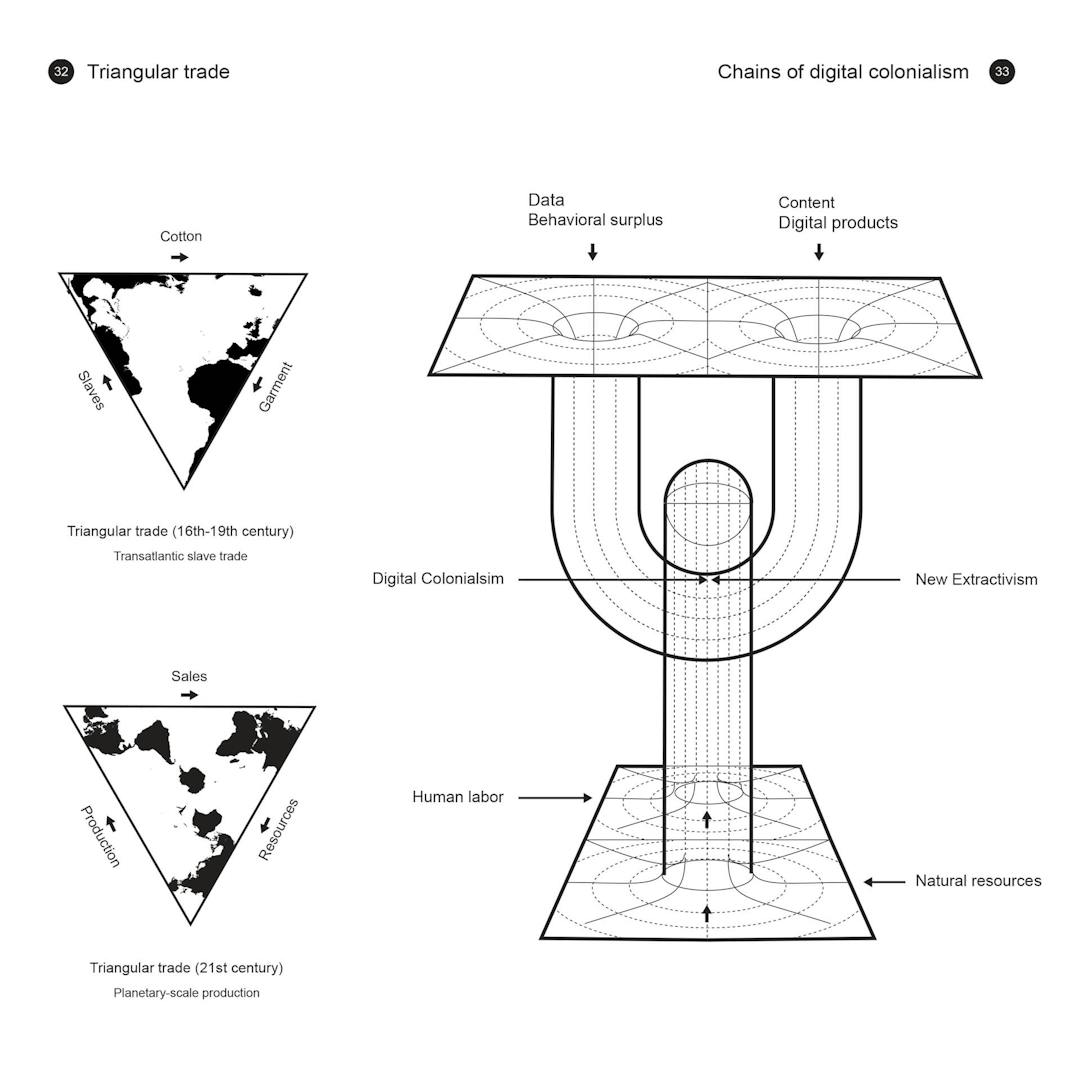

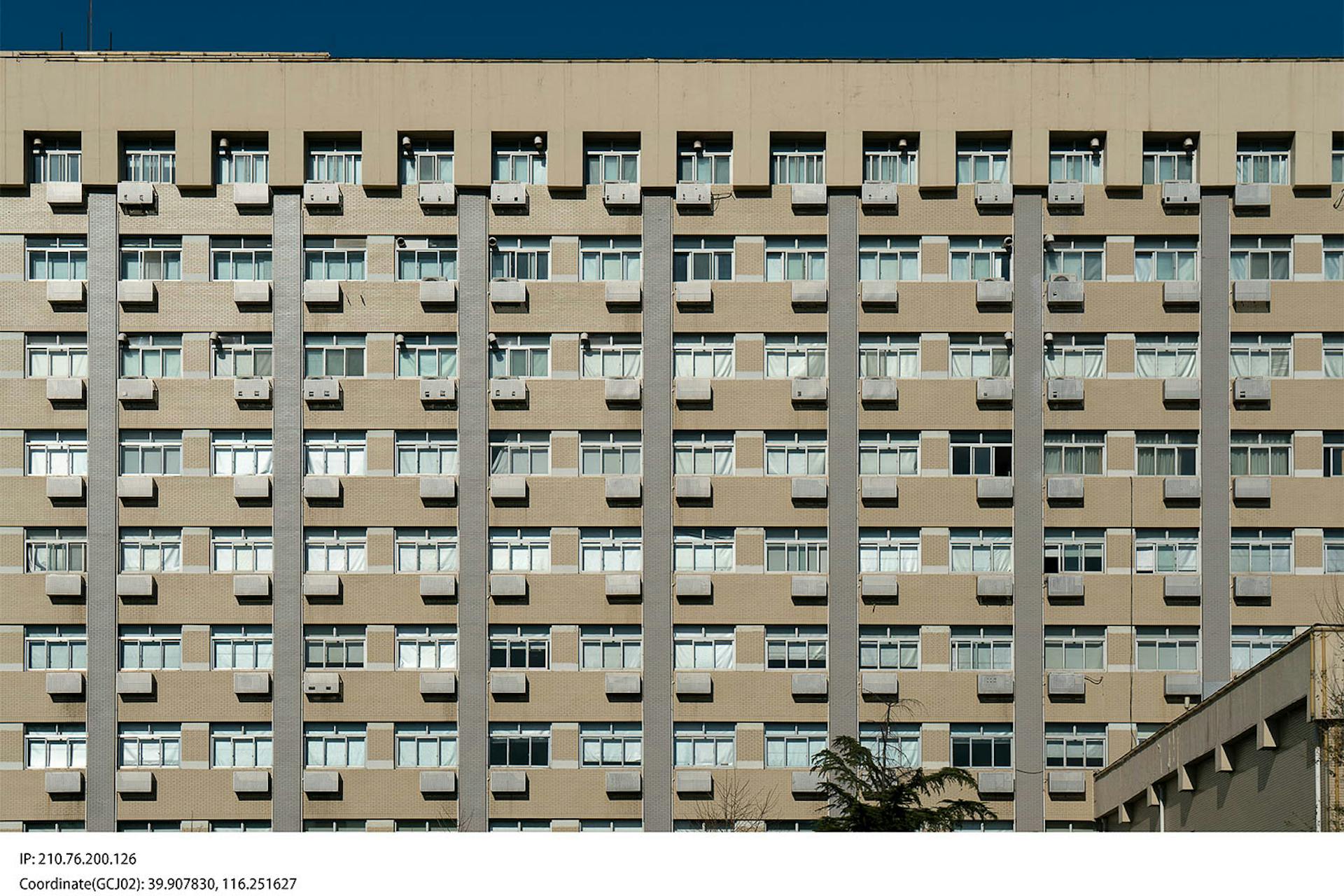

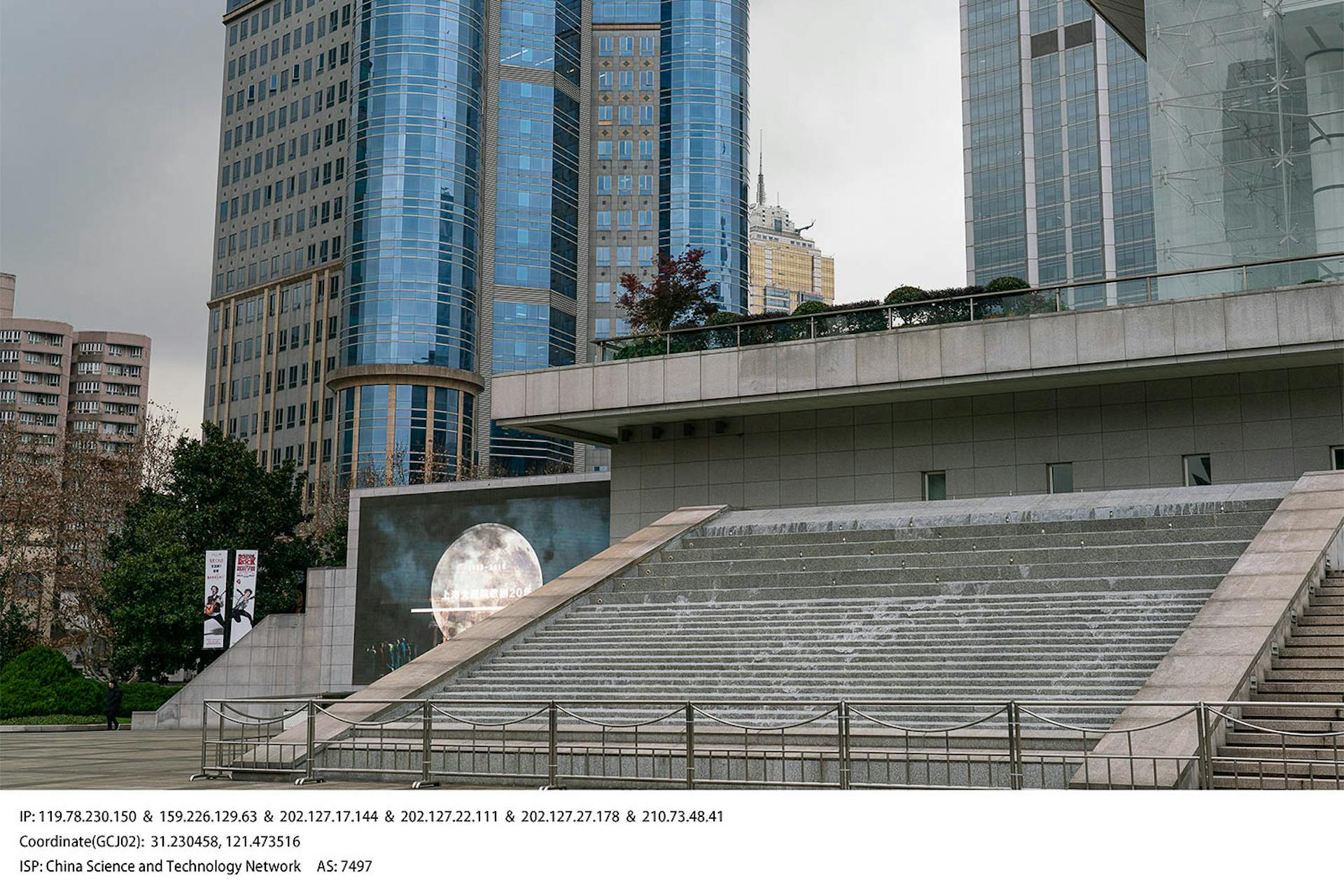

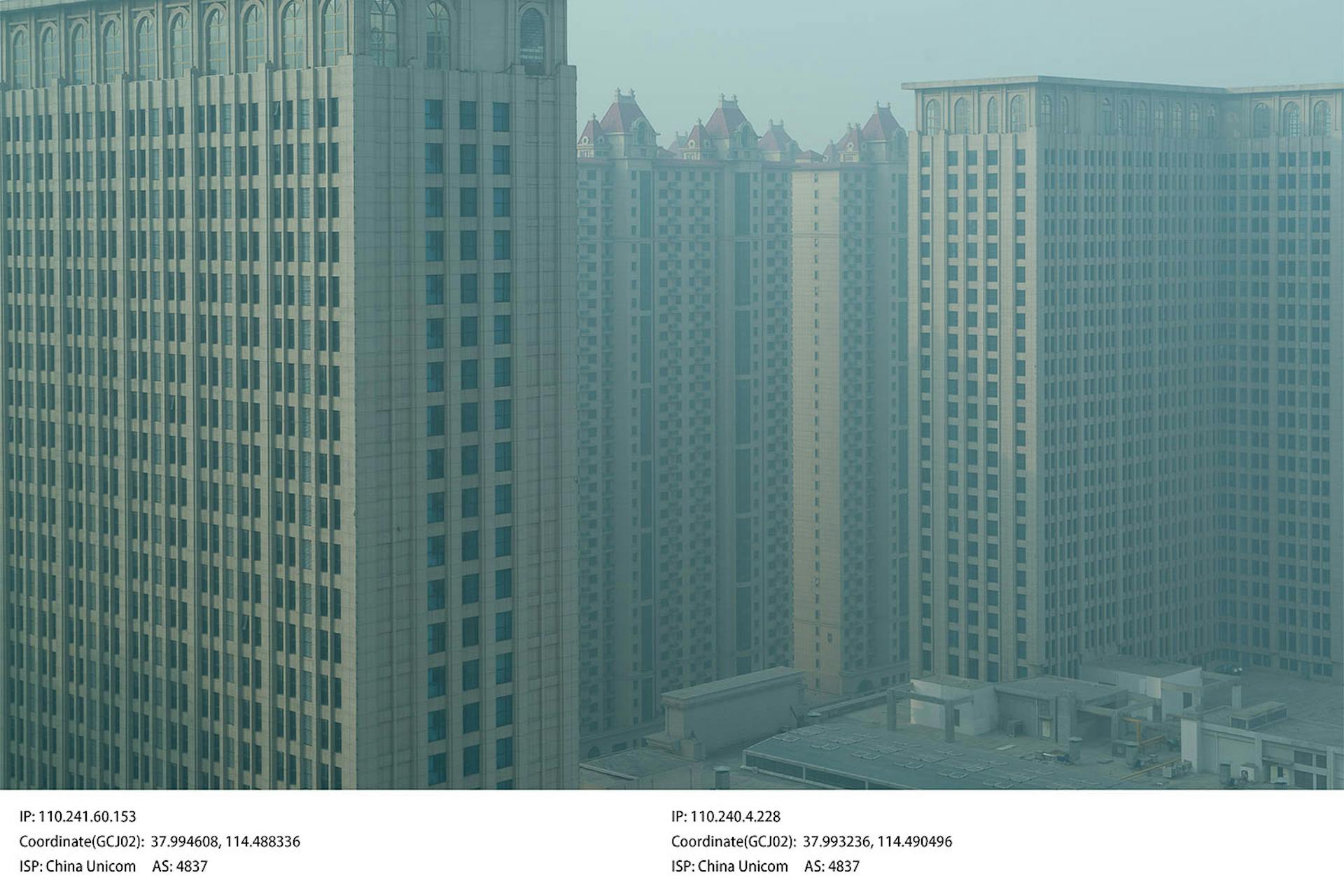

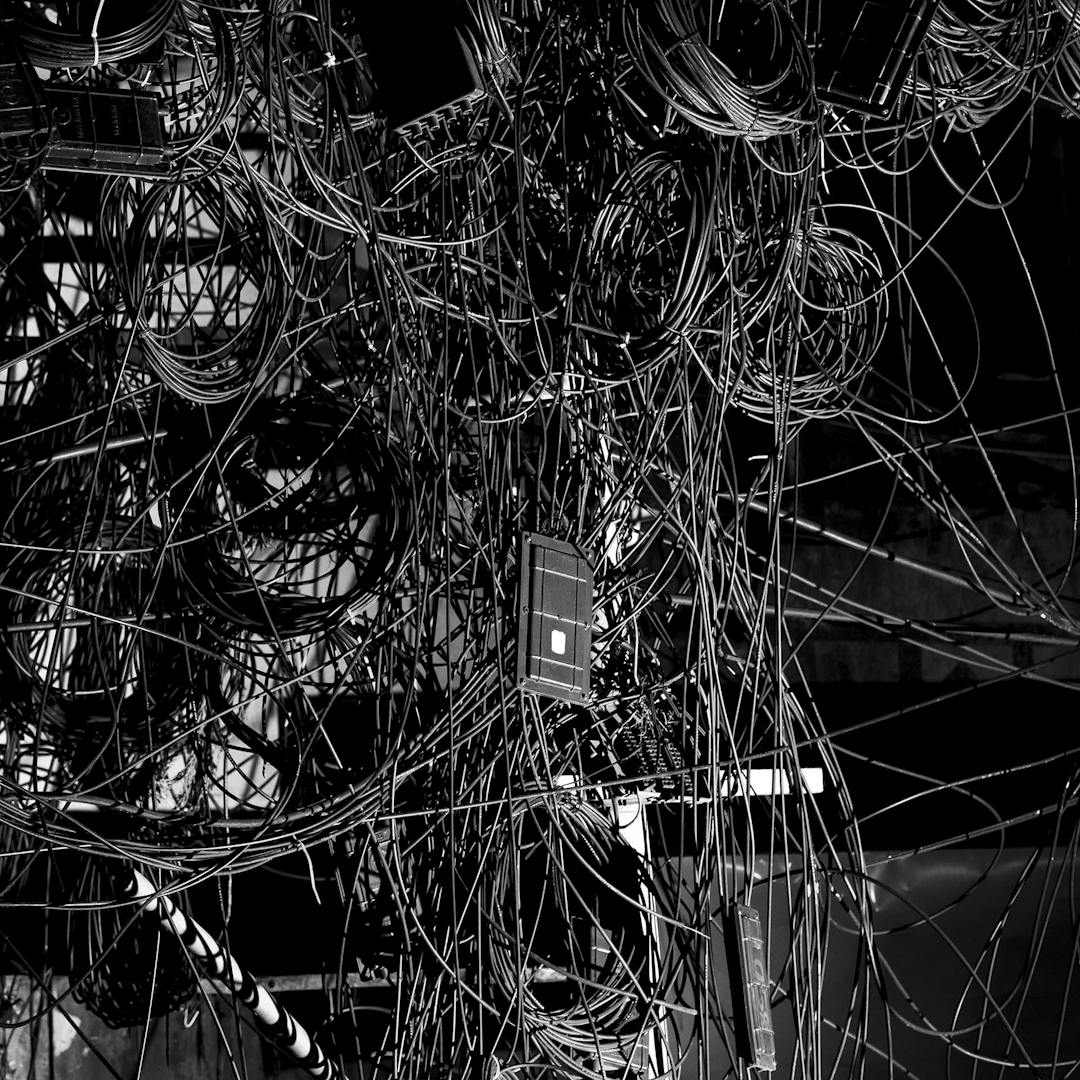

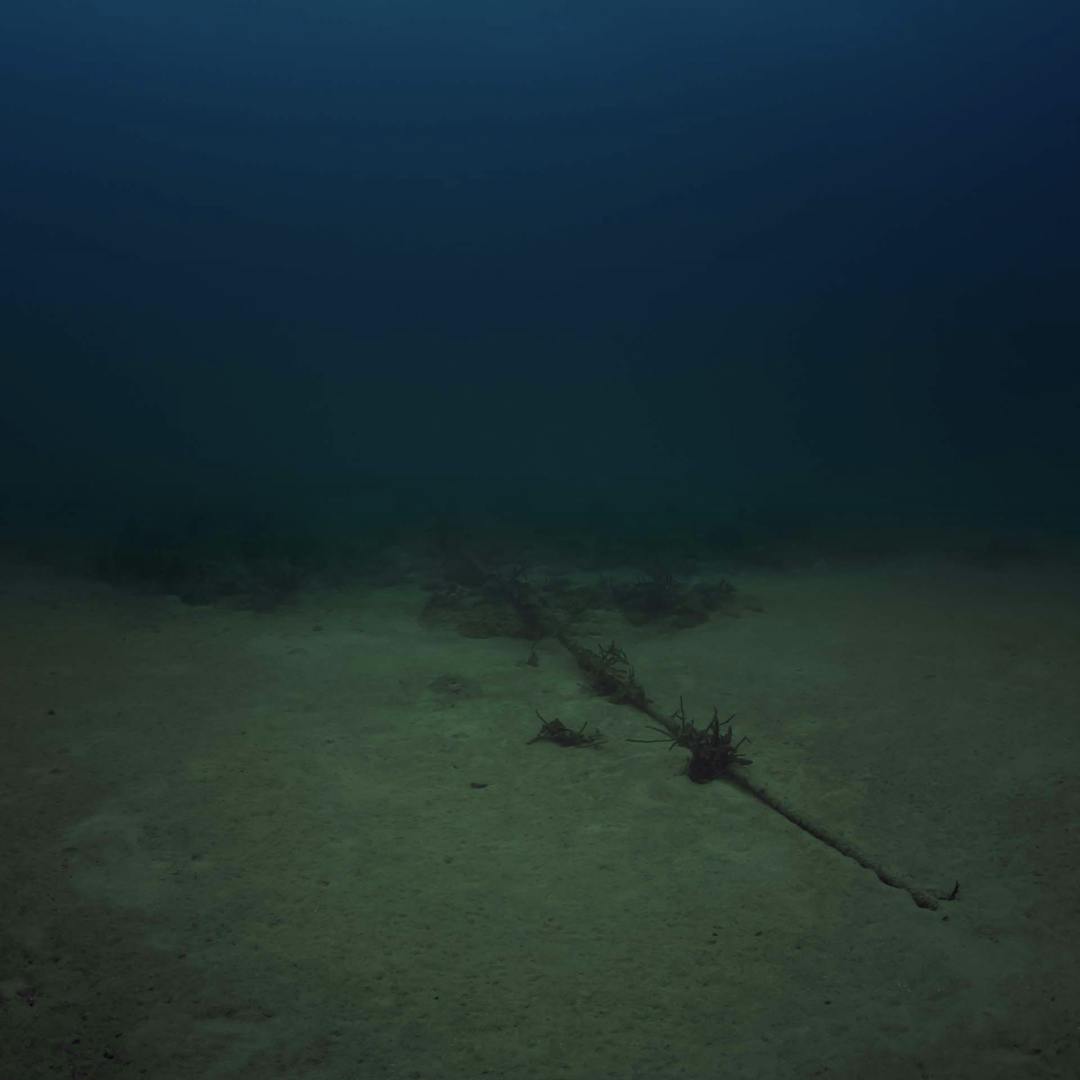

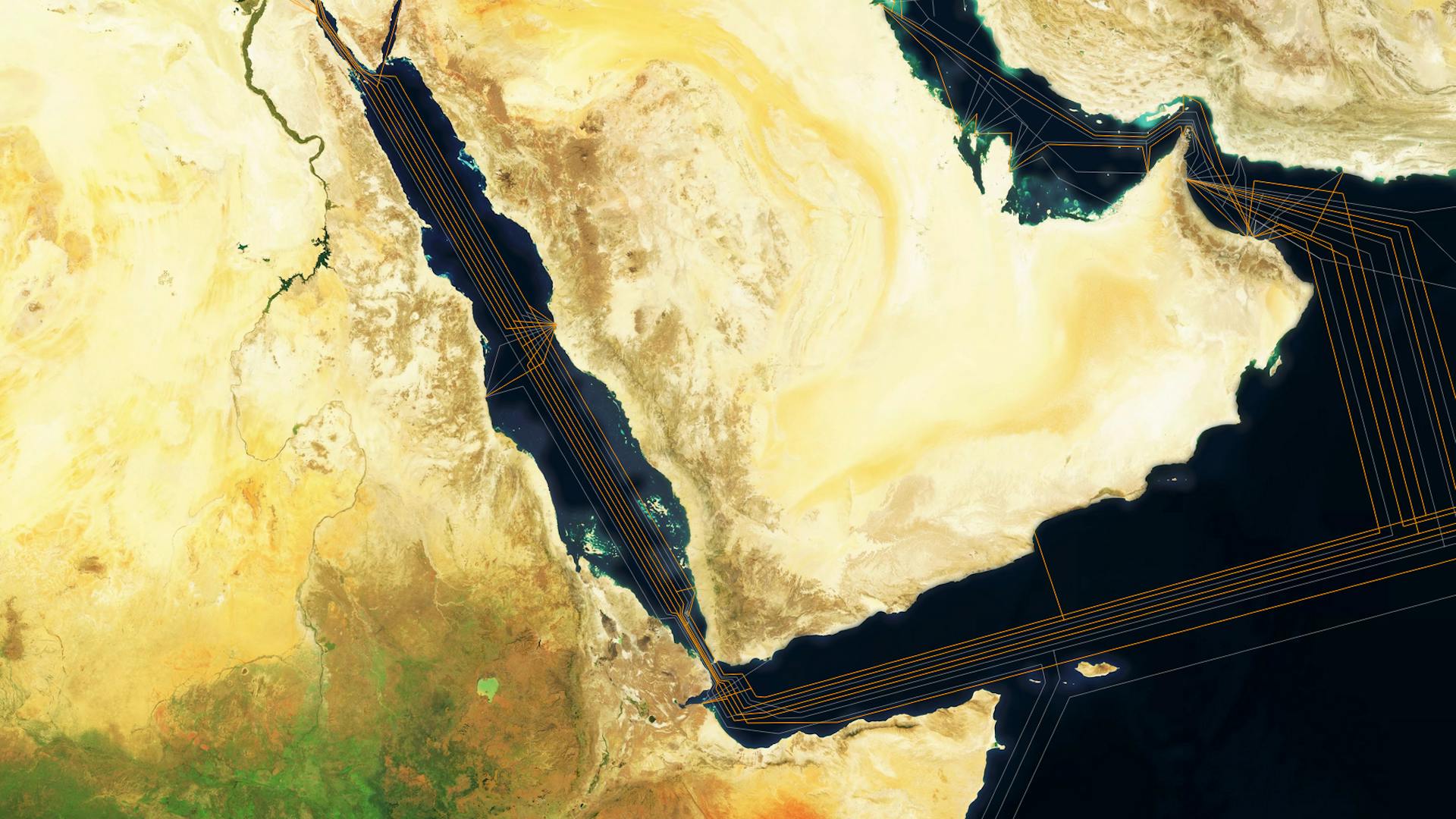

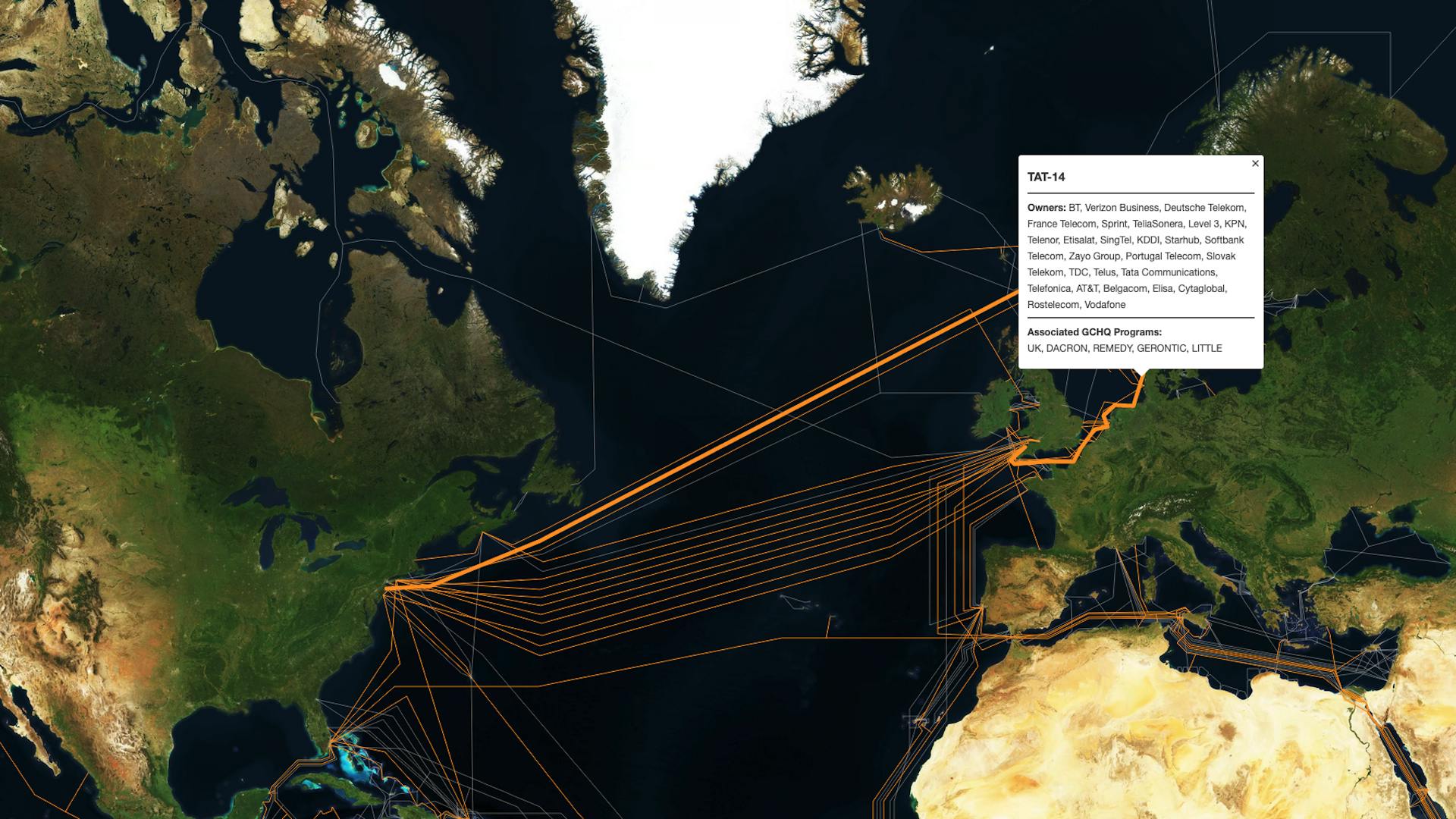

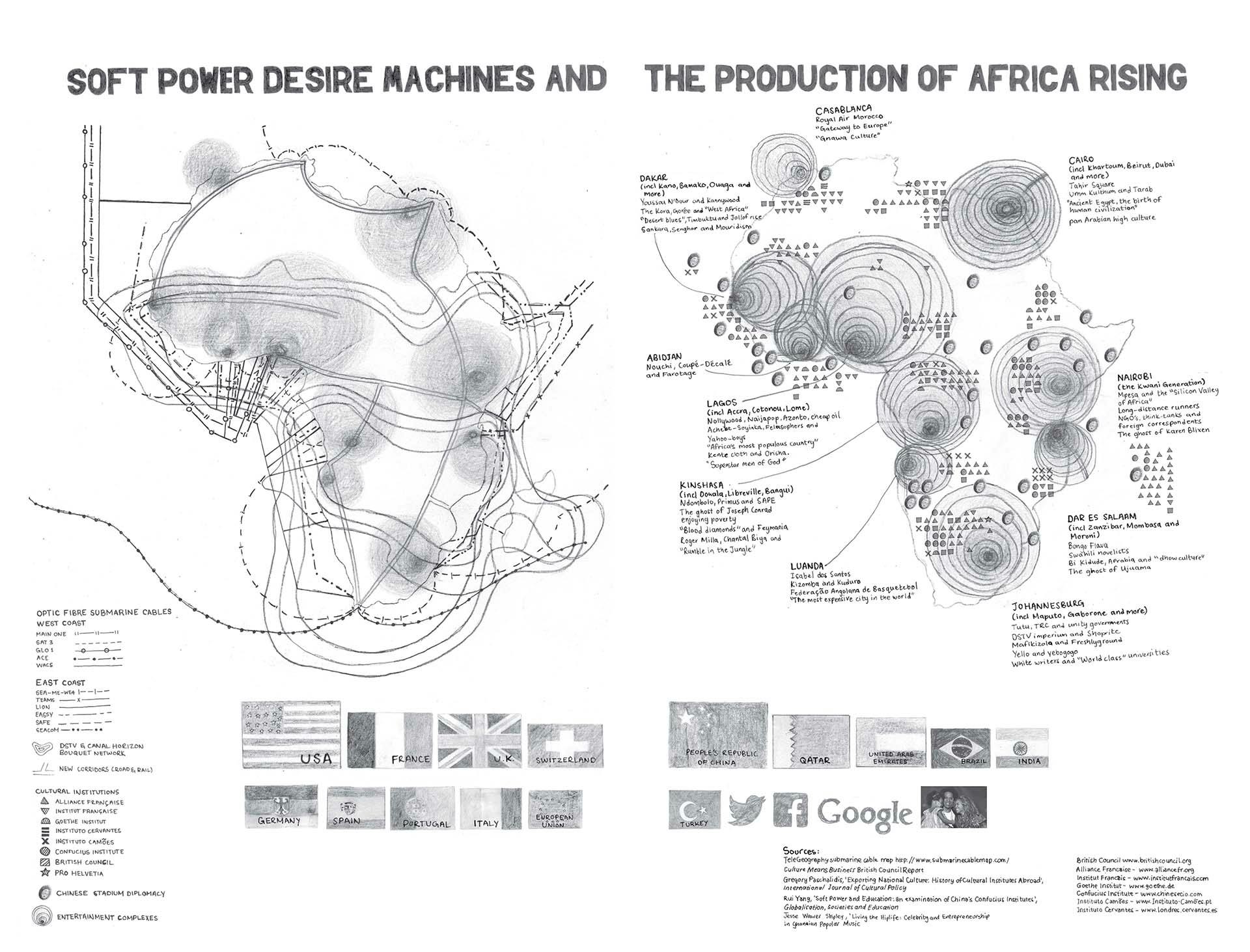

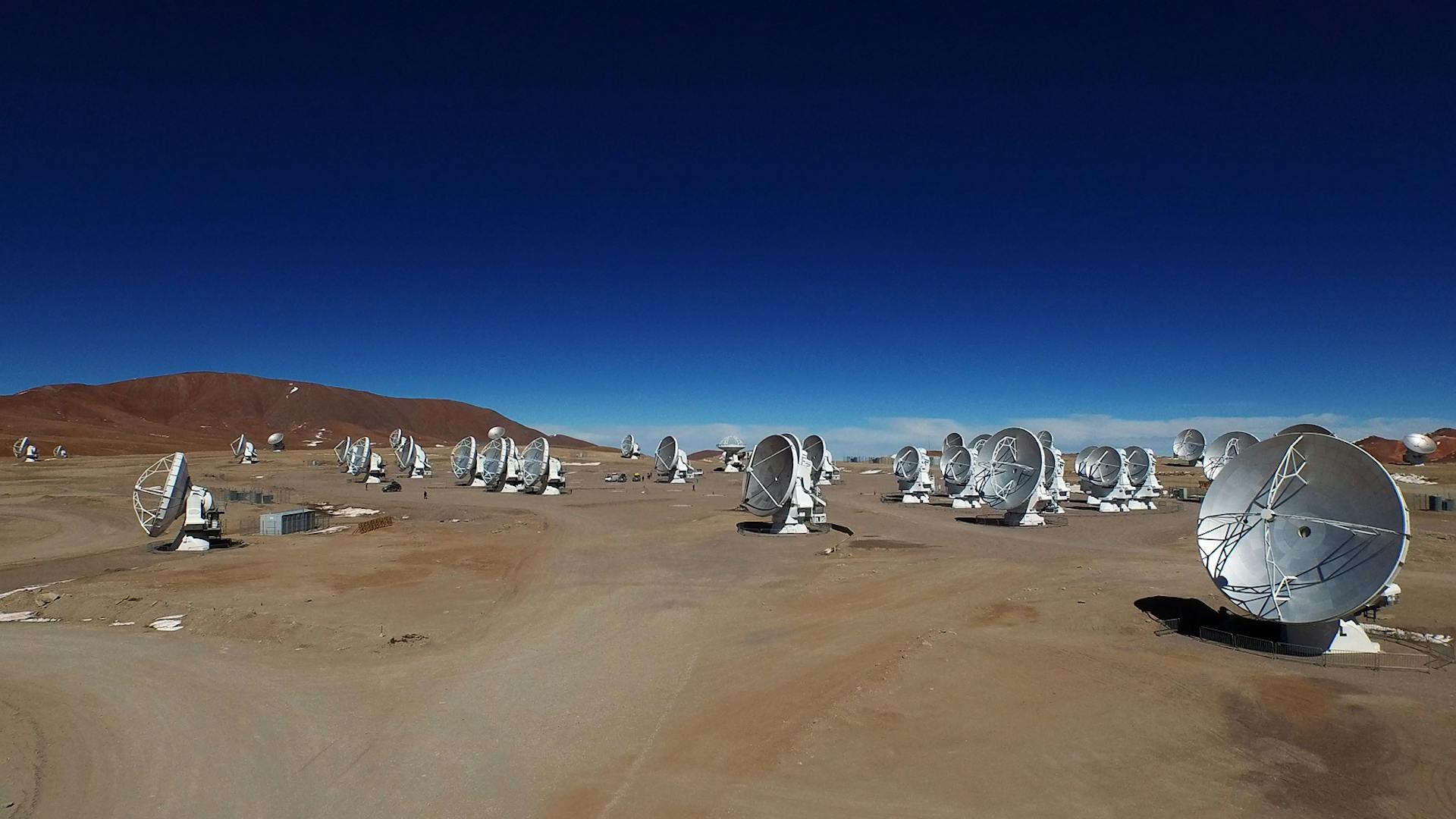

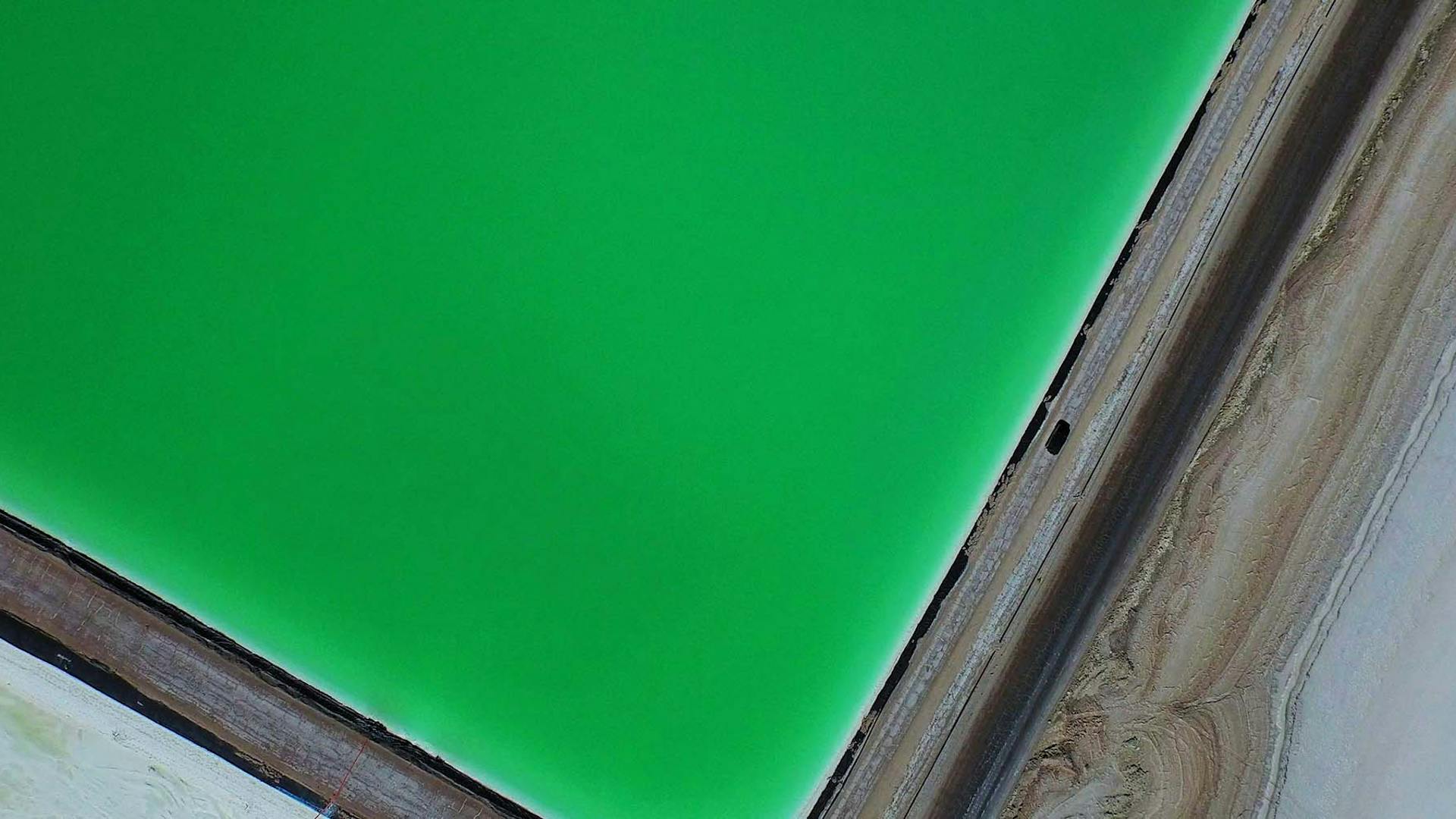

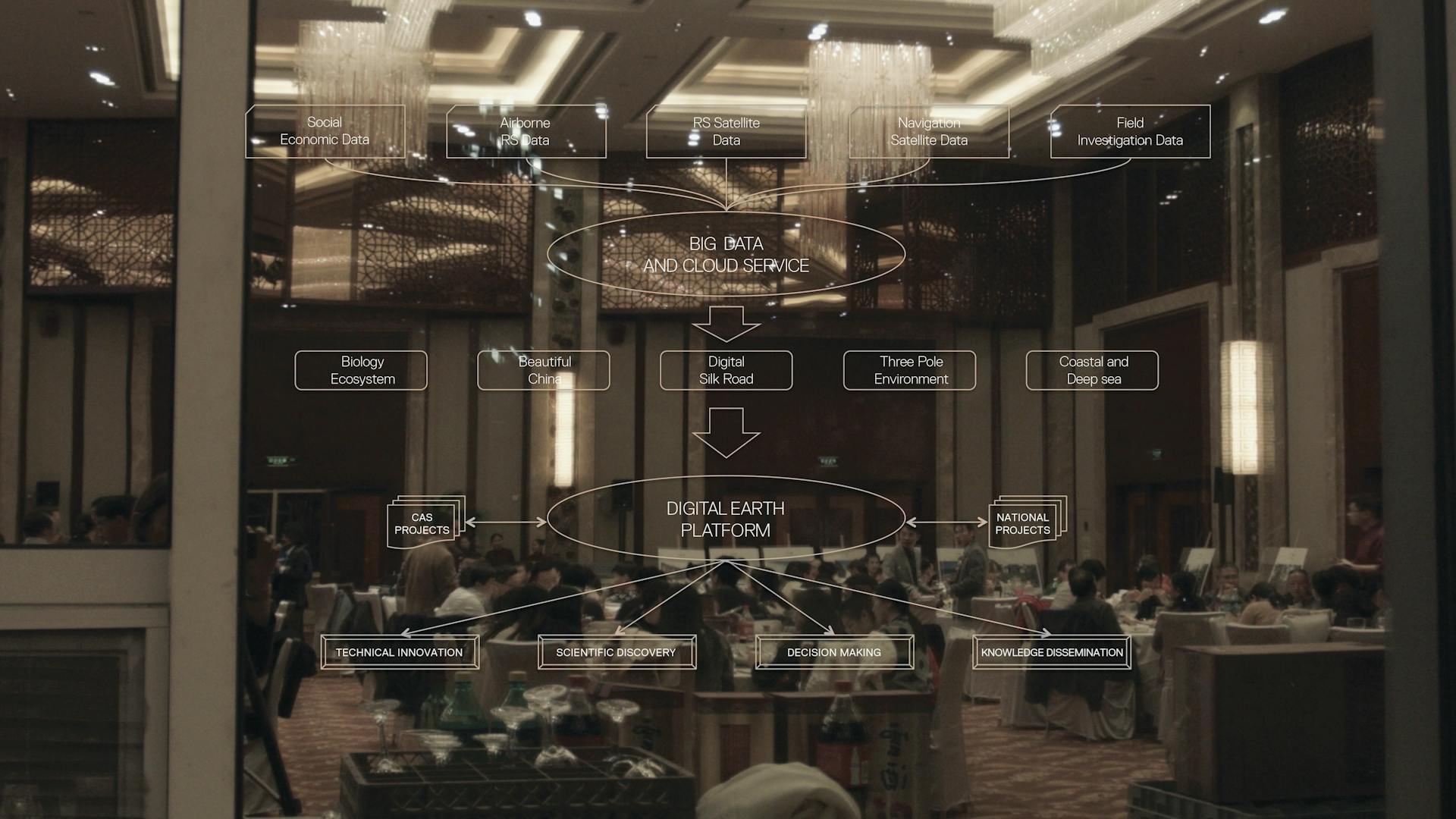

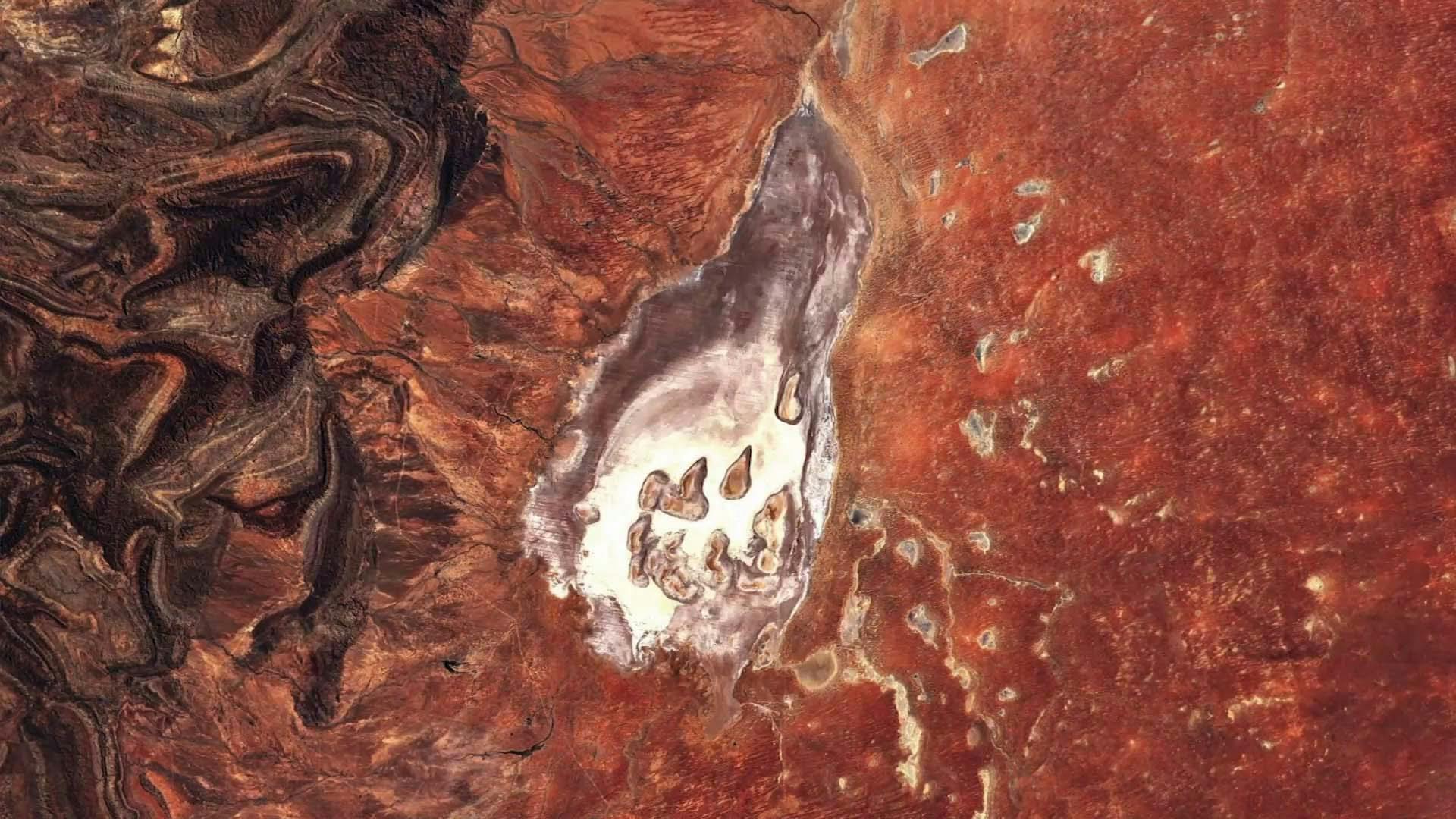

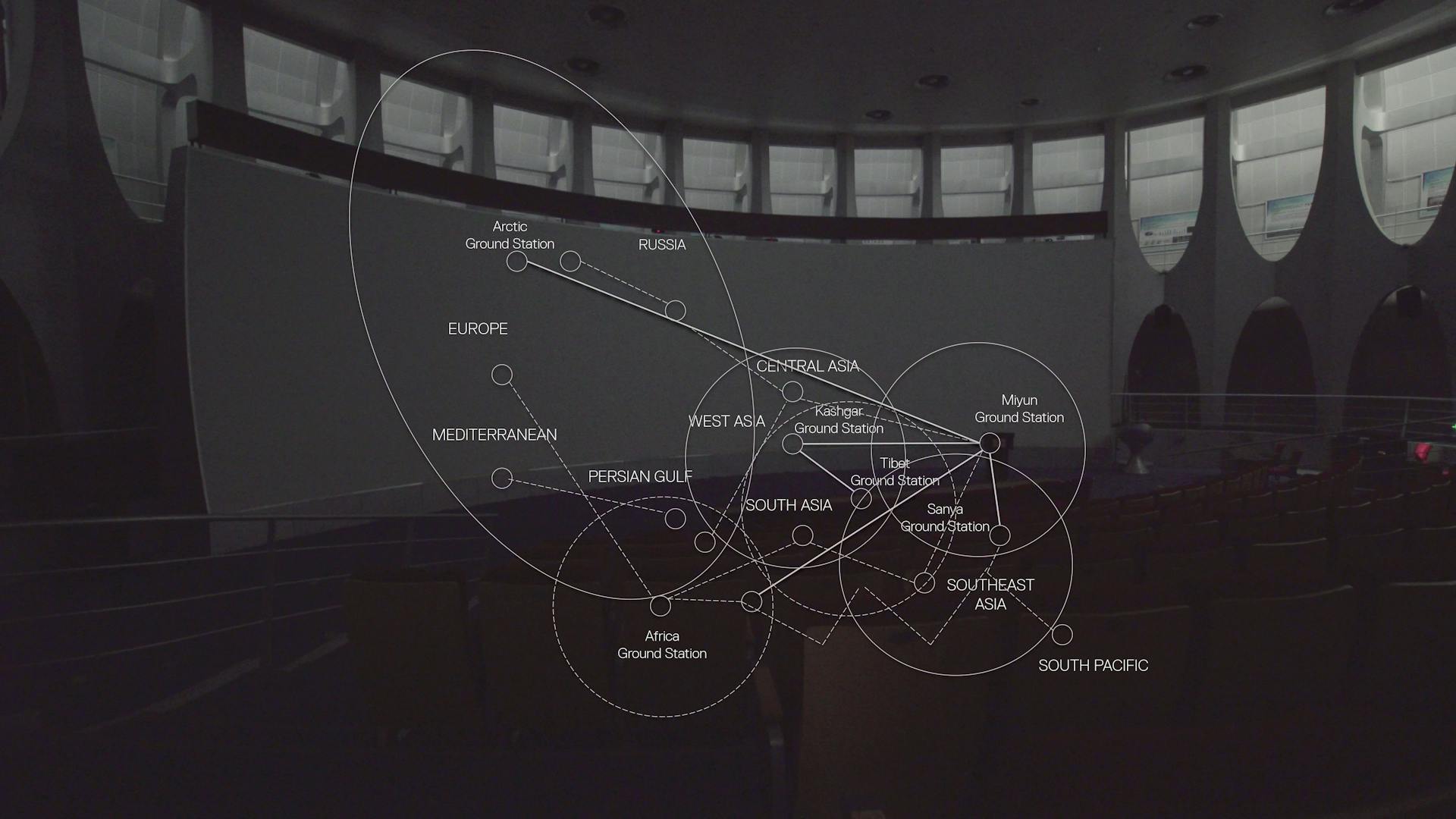

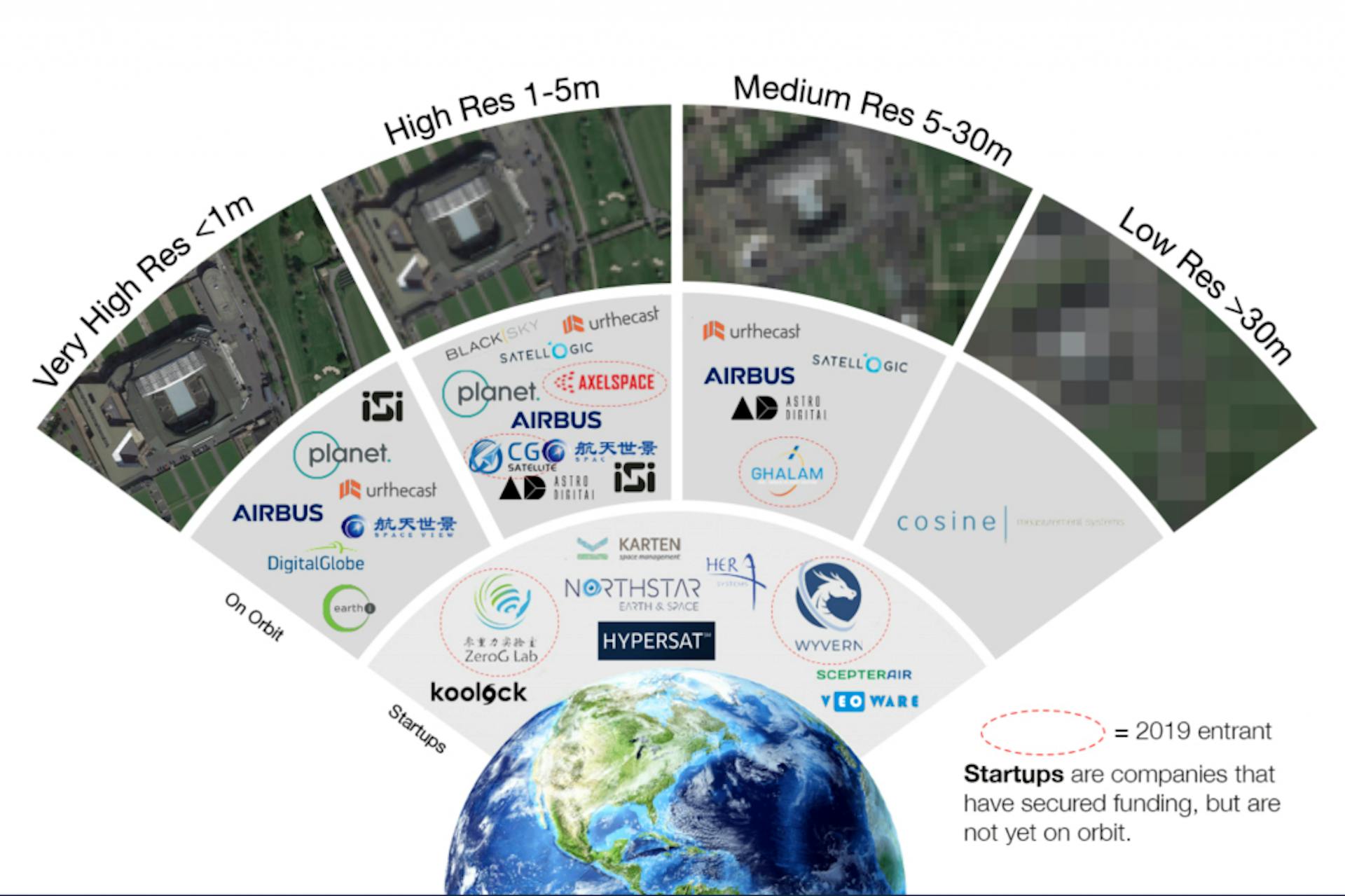

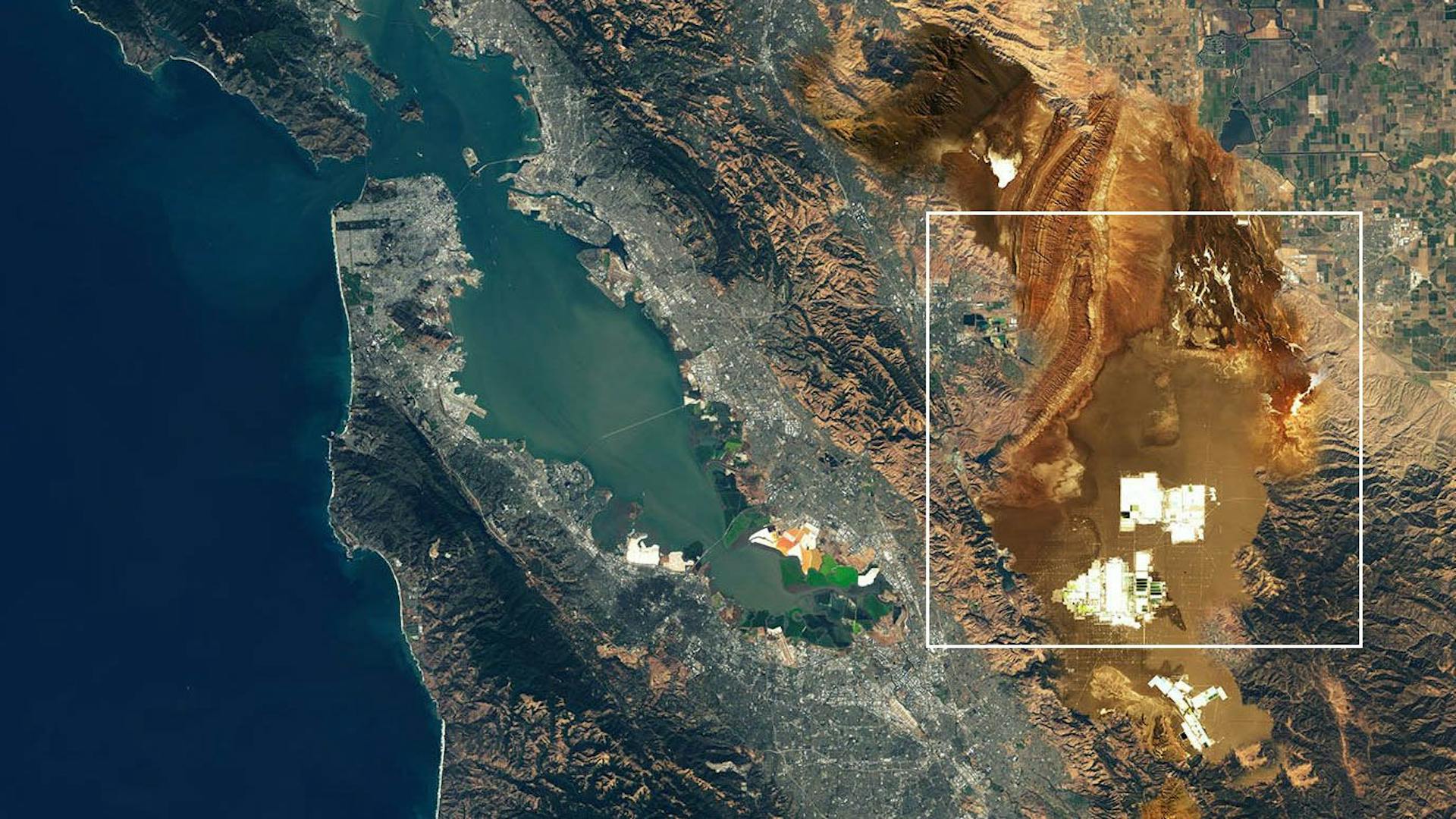

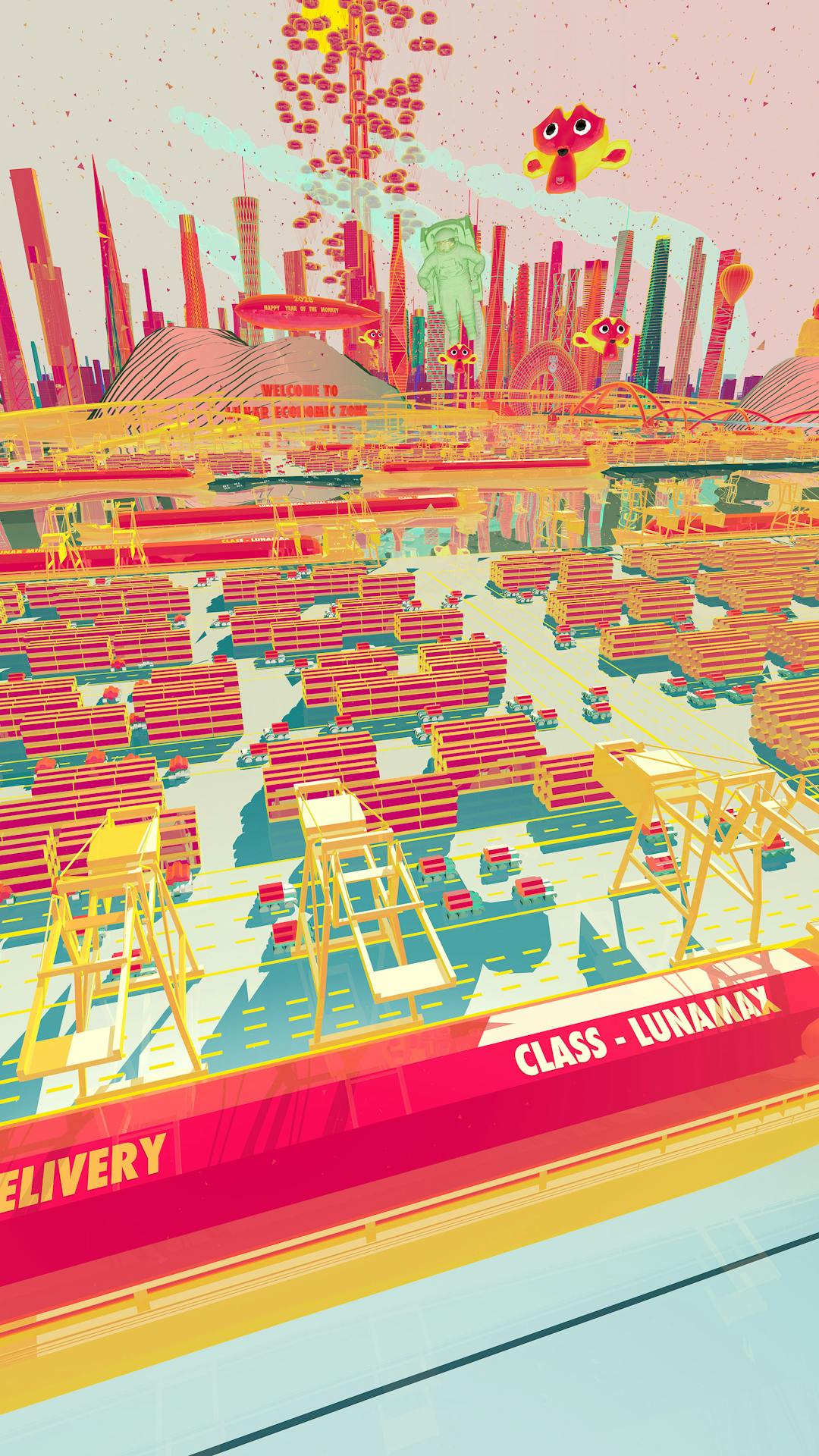

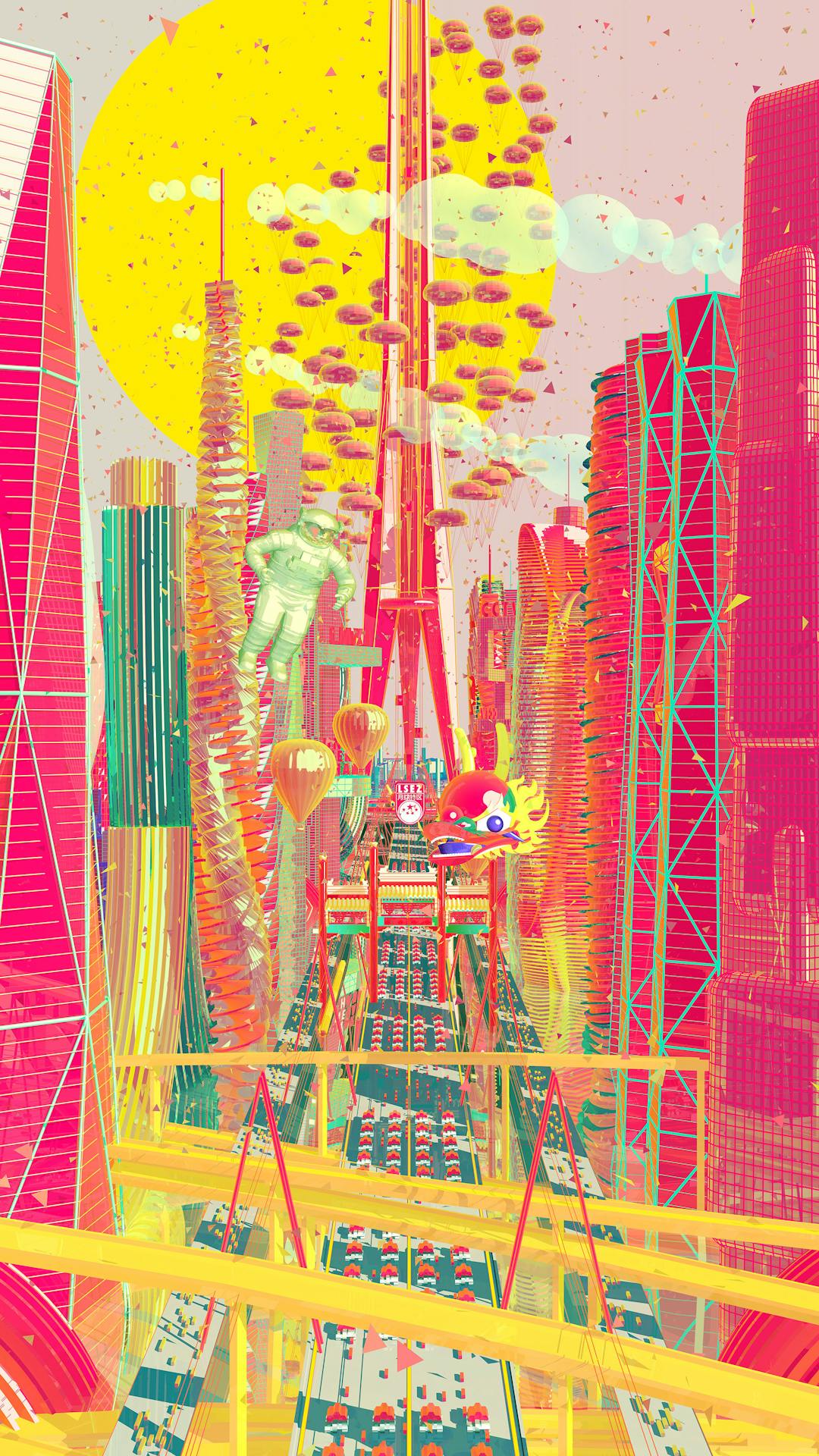

Cultural, economic and political structures have become mixed, overlayed, infiltrated, enhanced and undermined by new technological structures that together span the entire world. The computer in the palm of our hands is an entry point to systems that link lithium mines in Chile to offshore Russian data servers, to fiber-optic submarine cables in the Atlantic to freeports in Singapore, to corporate-owned satellites in orbit, to a burgeoning quantity of IP addresses and petabytes of data.

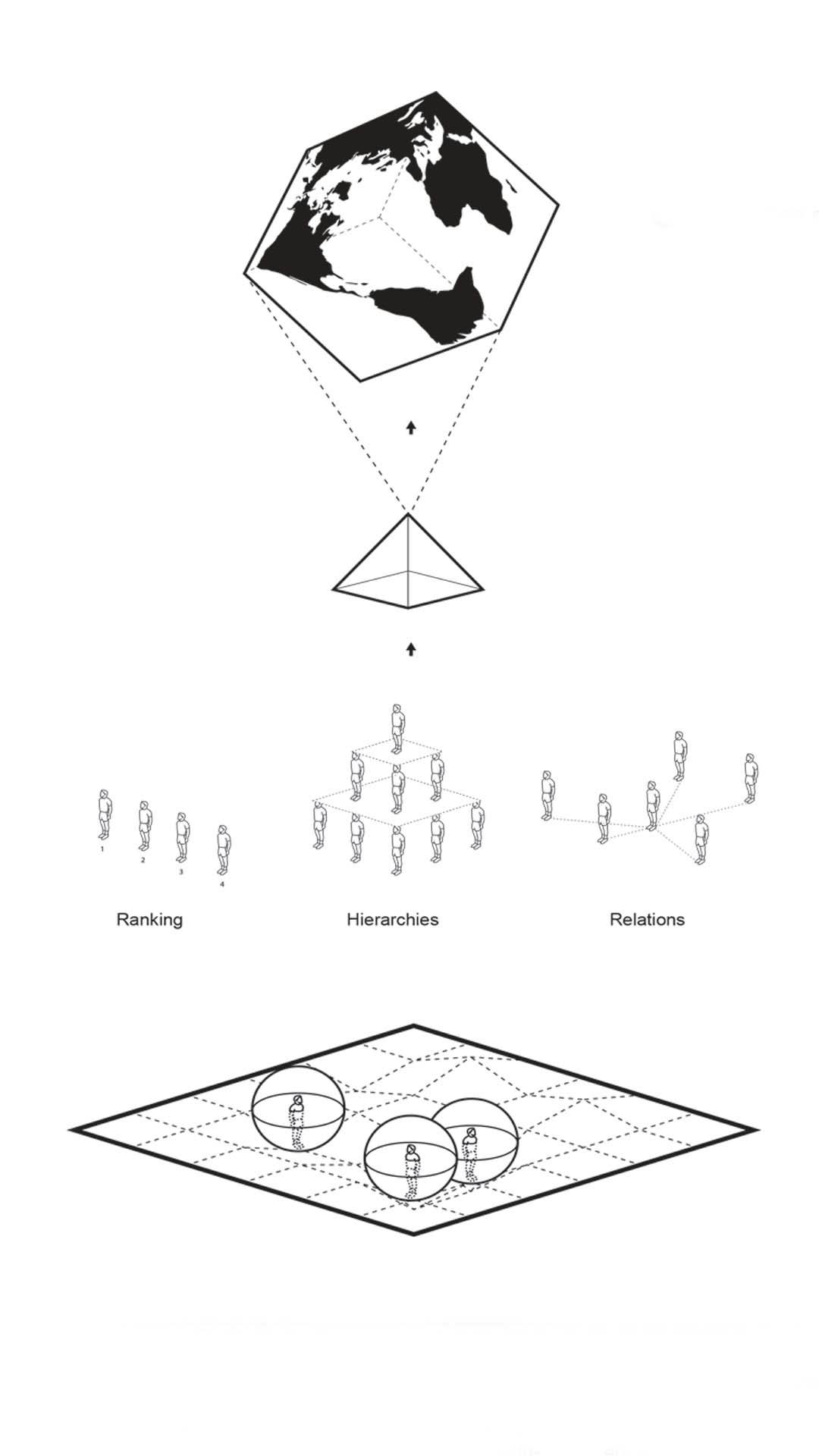

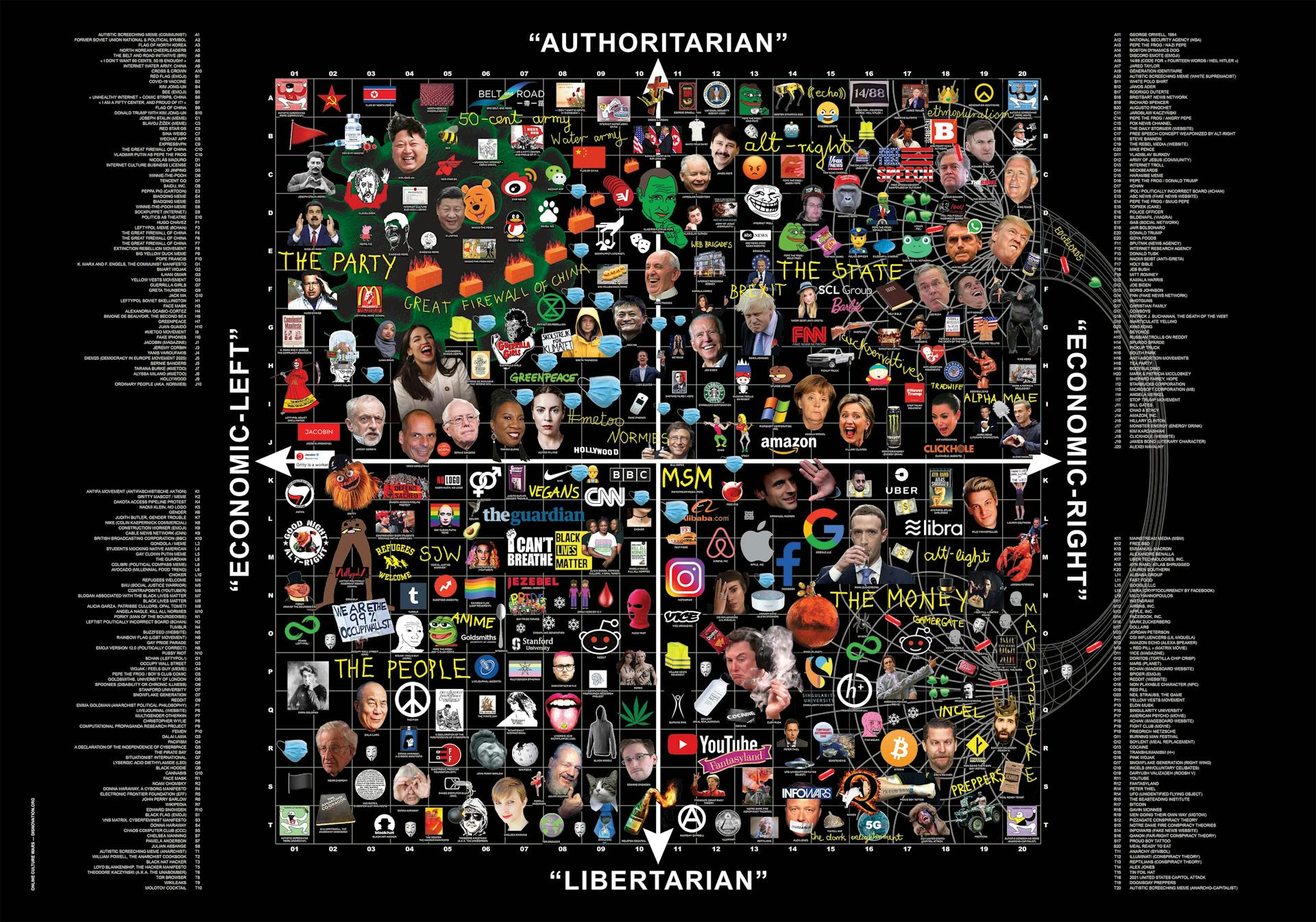

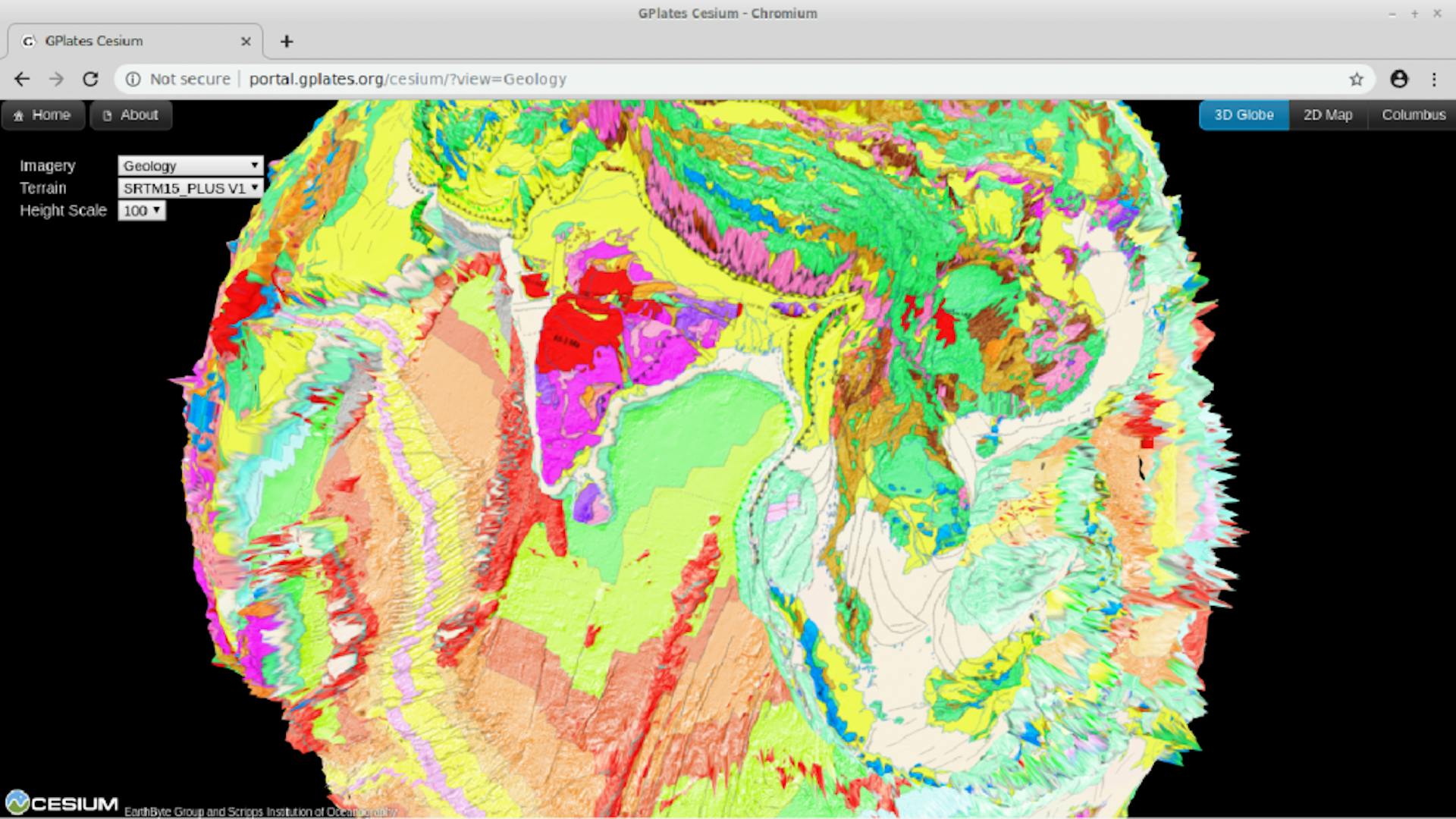

Navigating these technological realities–as in coming to terms with what is where and how parts relate to other parts and to bigger wholes–has become increasingly difficult. Also, the default instrument for navigating–the geospatial map–does not appear to be up to the task of providing insight into this technological, political and material sphere.

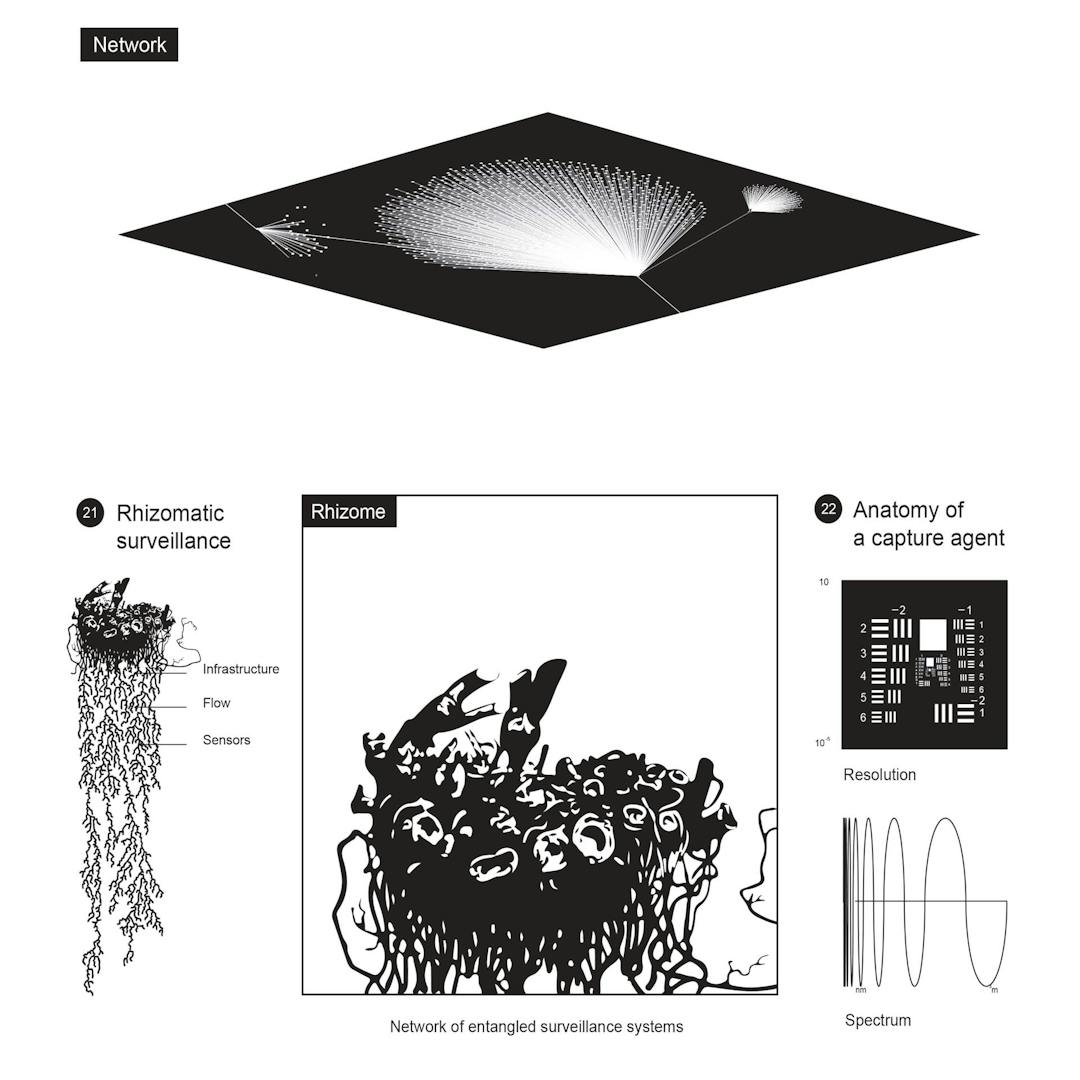

Geographical representation does not yield useful insights into or an overview of the entanglements of digital and physical structures. It cannot render the new folded, fractal borders that are created in digital space, nor does it properly represent how digital national borders materialize in places such as the cobalt mines in Congo that are owned by Chinese staterun companies, or in digital interfaces intended to discourage immigration. Cities as well as states are becoming increasingly non-local digital platforms, while cloud platforms have assumed roles that traditionally belong to governments, such as providing proof of identity and access to infrastructures.

There is also an underlying issue with cartography in general.

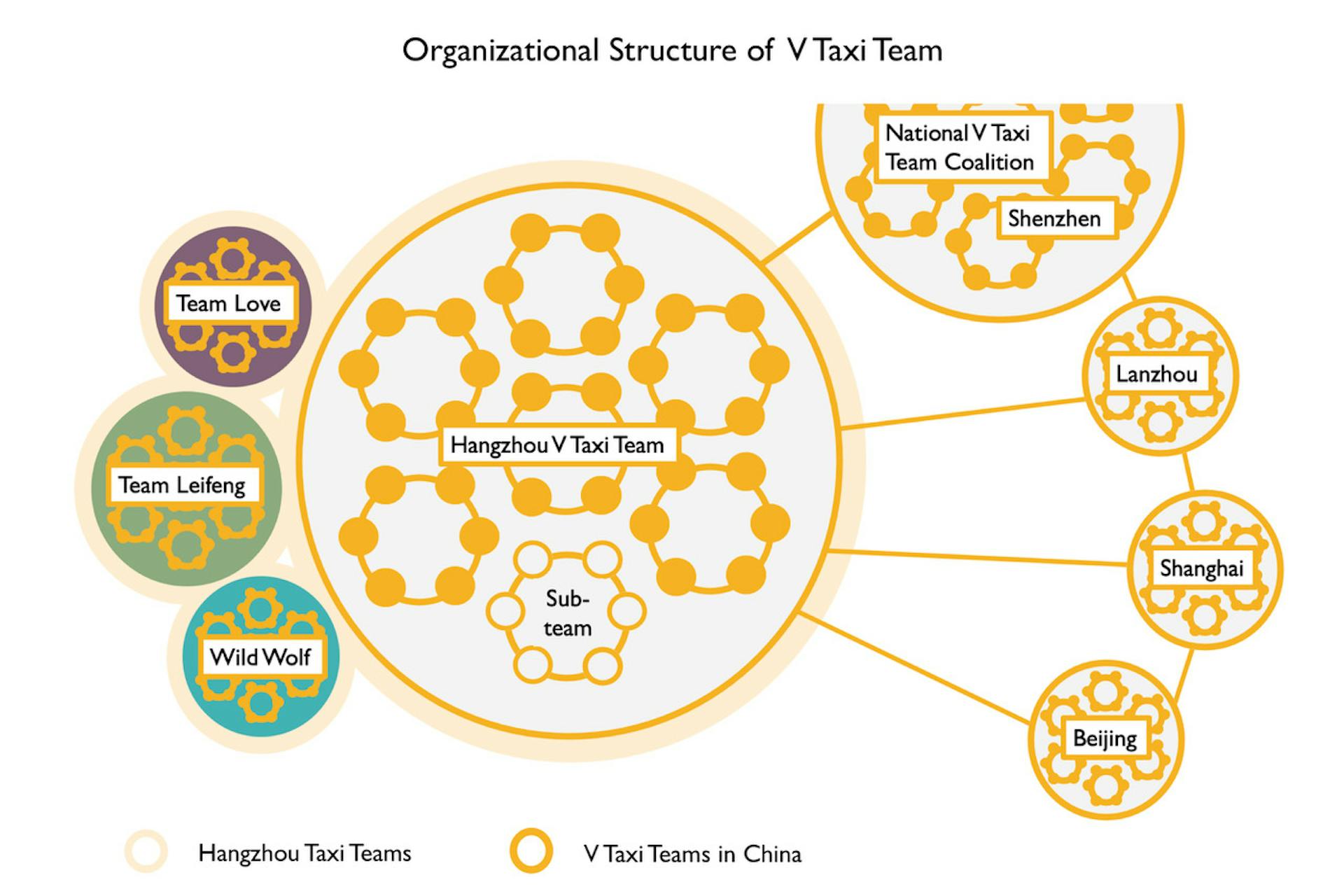

Maps have for centuries been a tool in the service of existing power structures. Cartography was vital to systematizing the Western colonial project and in turn reflected and codified its effects. Current corporate-run mapping systems such as Google Maps are designed to serve the needs of global and local market powers, and in doing so reflect once again a singular, implicitly normalized perspective that has inherited these traits of the colonial project. At the same time, maps fail to capture the lived realities that often counter any universalizing imperative. The many initiatives where people build their own infrastructures, or develop alternative organizational forms, all evince other kinds of world-making both with and against technology.

So, how then to navigate the non-universal, fractal scape of altered realities with non-local borderlands? Clearly, other kinds of maps are needed to guide us through these new formations in hybrid spaces.

Editorial principles

Multivocal—Multifocal

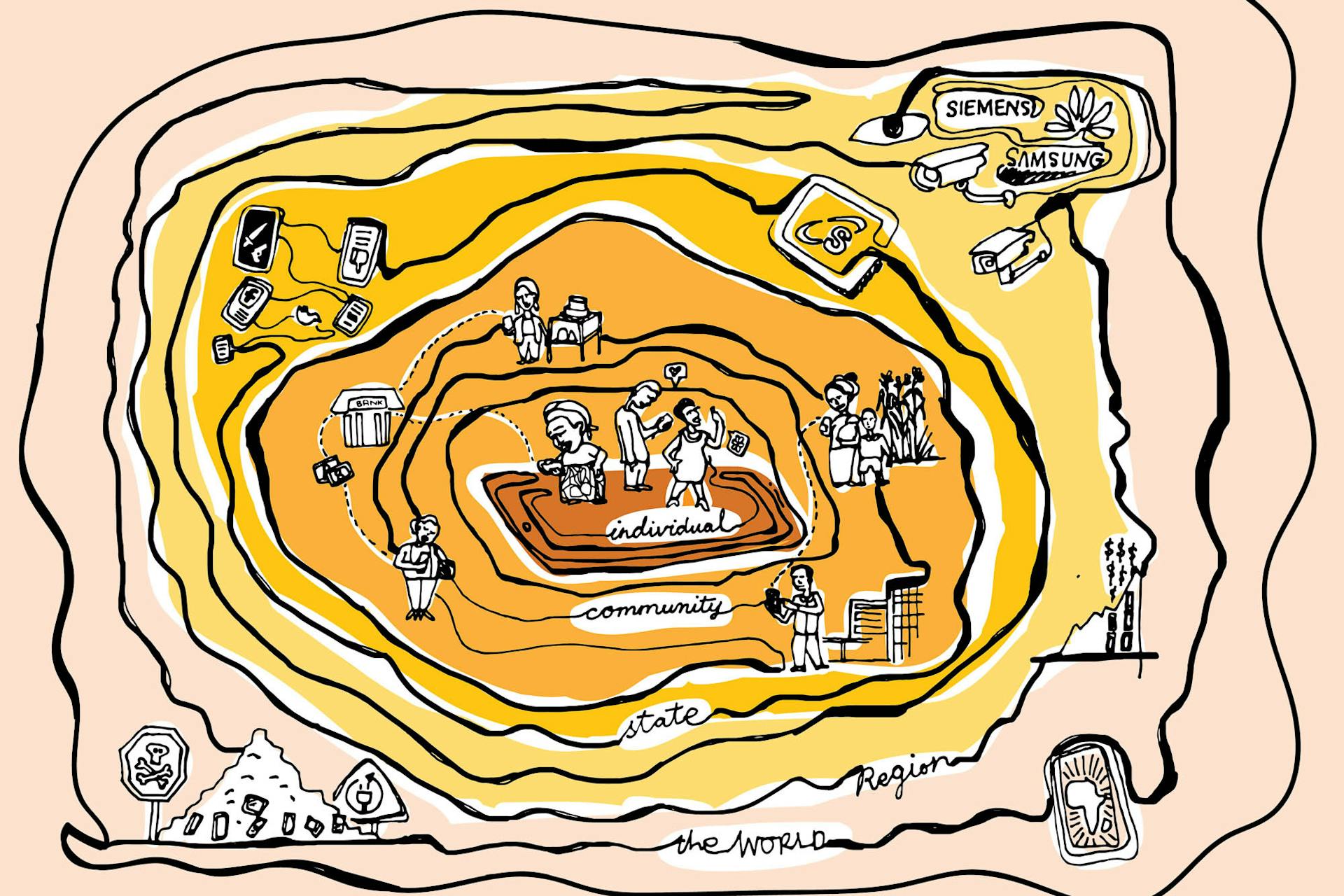

Vertical Atlas proposes a multifocal as well as multivocal approach, meaning that not one standardized perspective informs the depictions of the world. Rather, the project adopts different perspectives and techniques in order to acknowledge realities from different cultural and political perspectives and different biological and machinic embodiments. Breaking down the problematic, yet all too common, logic of universal and linear technological development, it aims to shift focuses to regions, actors and voices that do not fit the universal narrative, but rather challenge and repurpose it for a more pluralistic vision of digital technologies.

scales

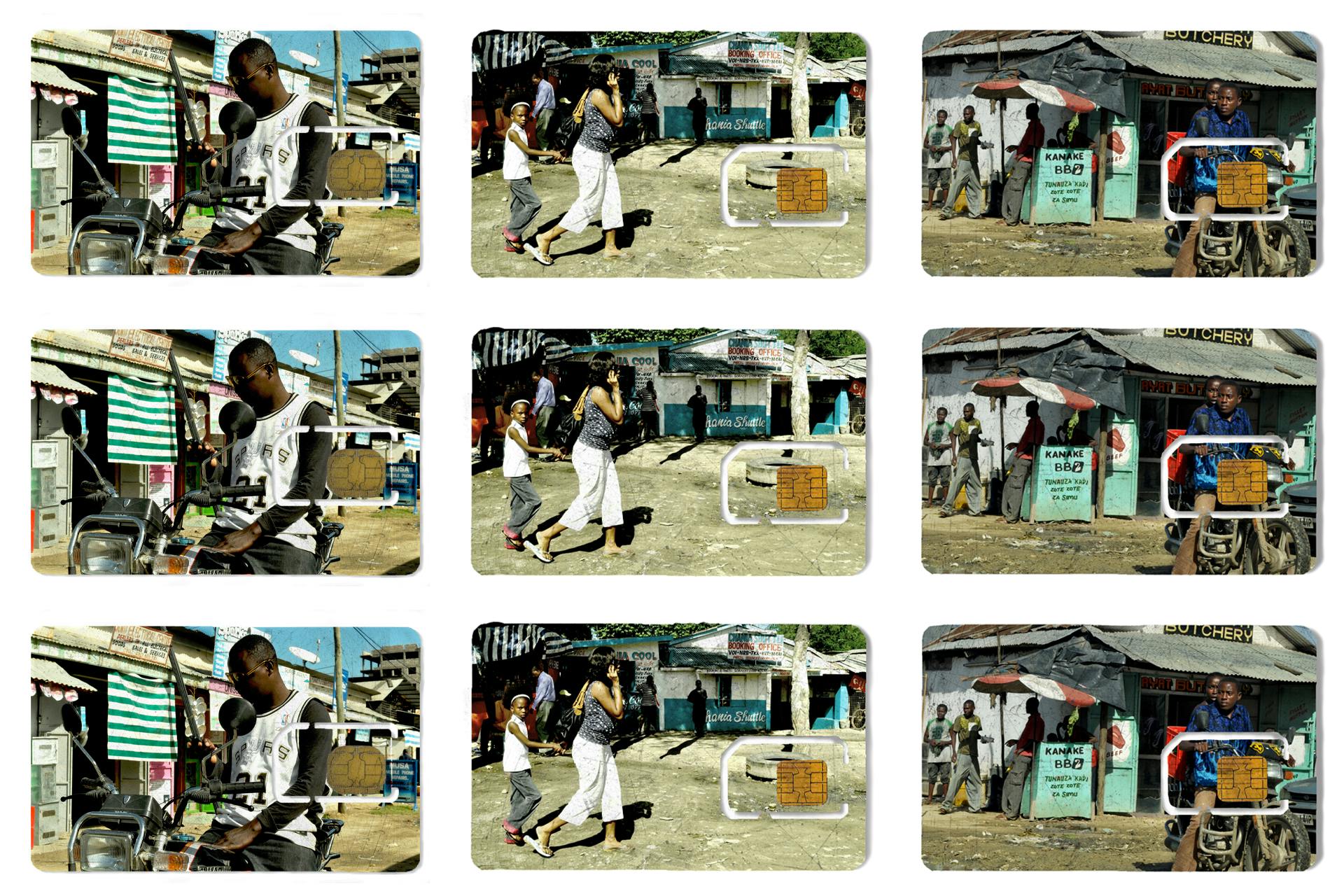

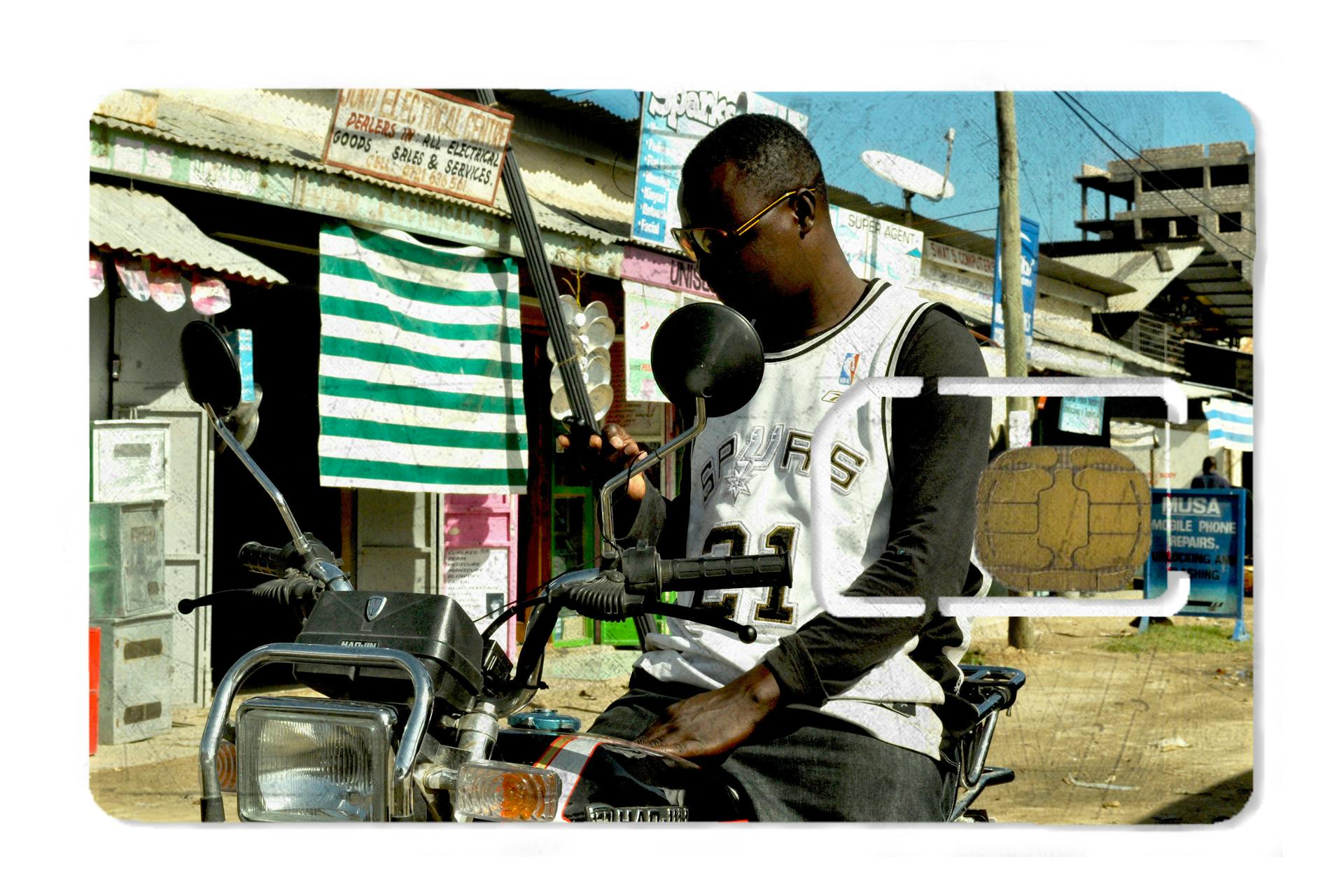

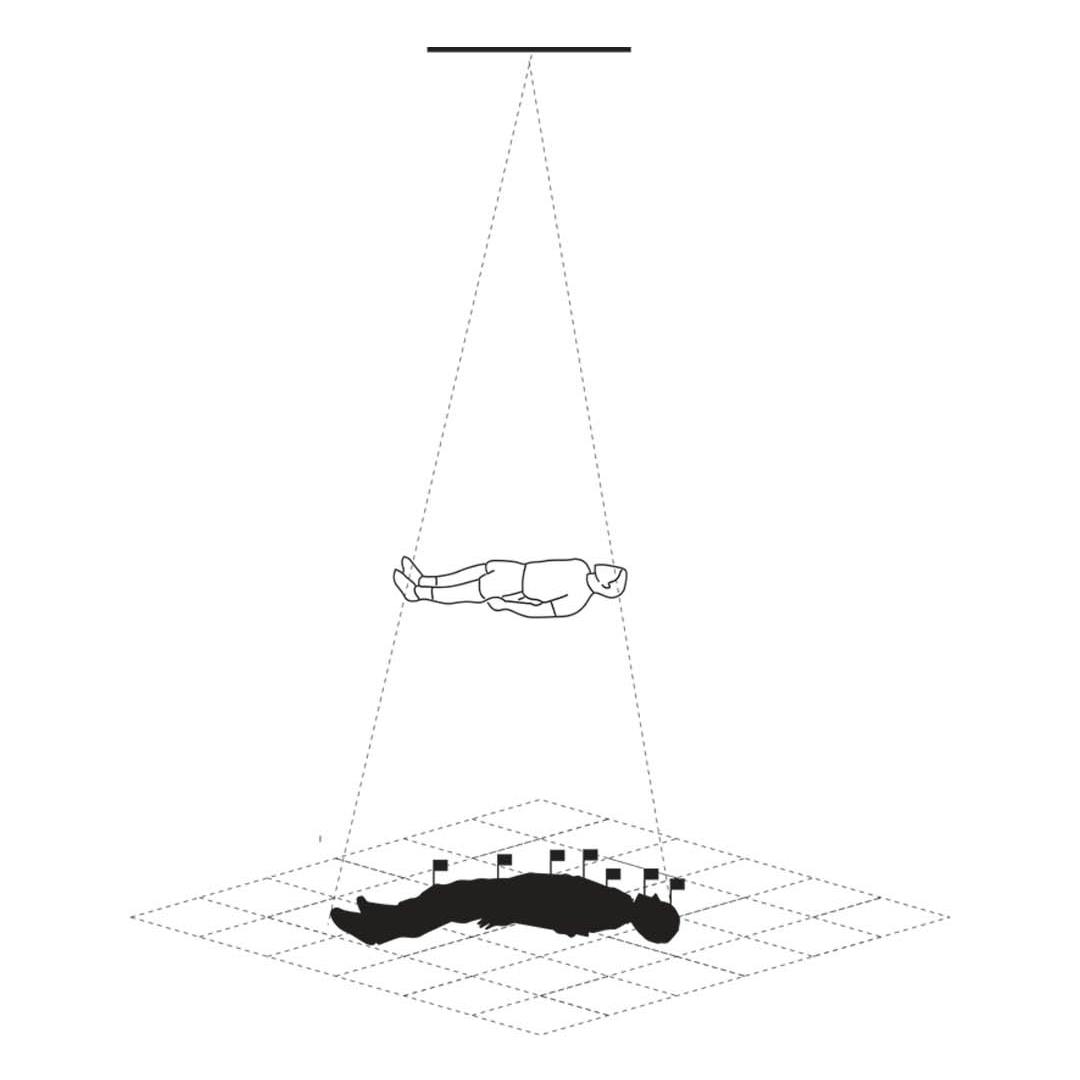

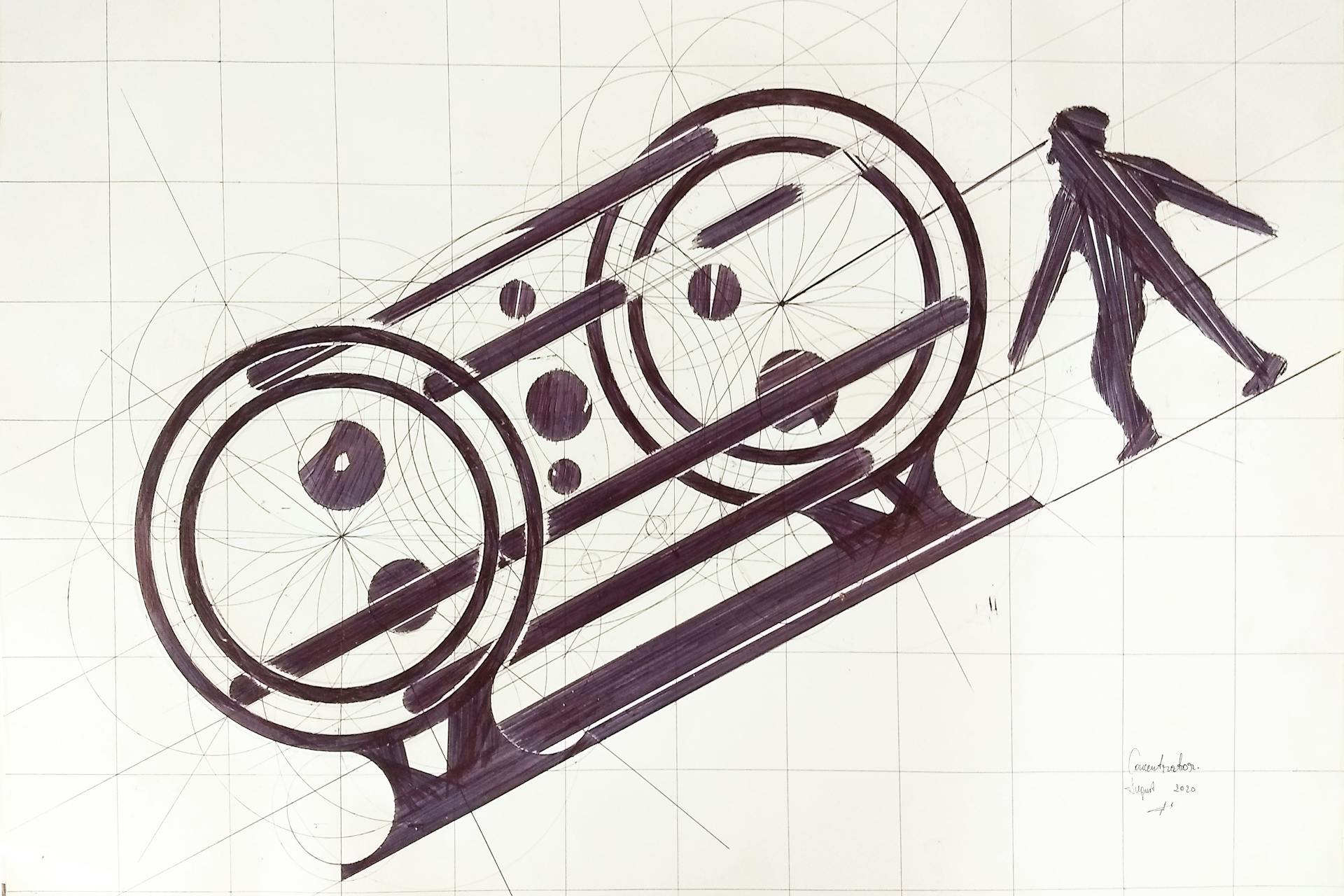

Vertical Atlas is organized by a logic of successive multidimensional scales of actors in the technological sphere. The book opens with maps relating to the scale of the individual human body and then zooms out to the scale of local platforms, cities, the nation state and its nonlocal borders, cloud platforms, infrastructures, earth observation and mining, to cosmological frames. As can be seen, this scaling is not a smooth process–each scale accommodates different techno-political structures and particular qualities of frictions.

Frictions

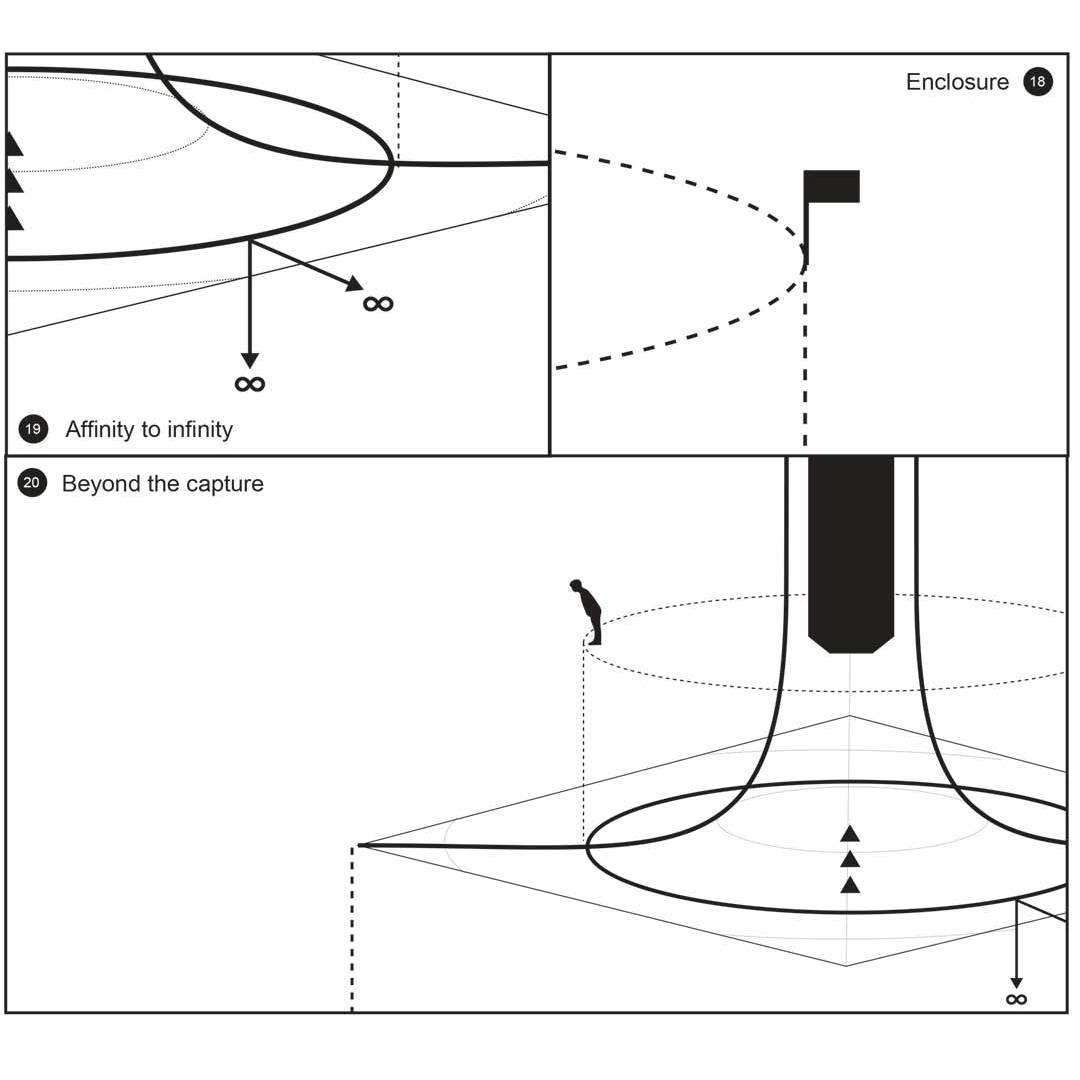

This atlas does not aim to depict the entirety of the landscape of the technosphere. Instead, each of the maps focuses on a particular friction or fault line that reveals a characteristic dynamic. Some maps explore how frictions between the citizen and the user play out, others focus on the simultaneous overlap as well as the incongruence between the nation state and the cloud platform. Yet others work with the metaphysical dimensions of cosmotechnics–how assumptions about the nature of reality shape the functions of technologies and vice versa.

Ultimately, Vertical Atlas is a book, a solidified, stabilized distillation of highly dynamic phenomena. As a book that took some time to create, it does not try to capture so much the fleeting now, as a photograph would, but is better compared to a film–to a composed sequence of shots from different angles and distances.

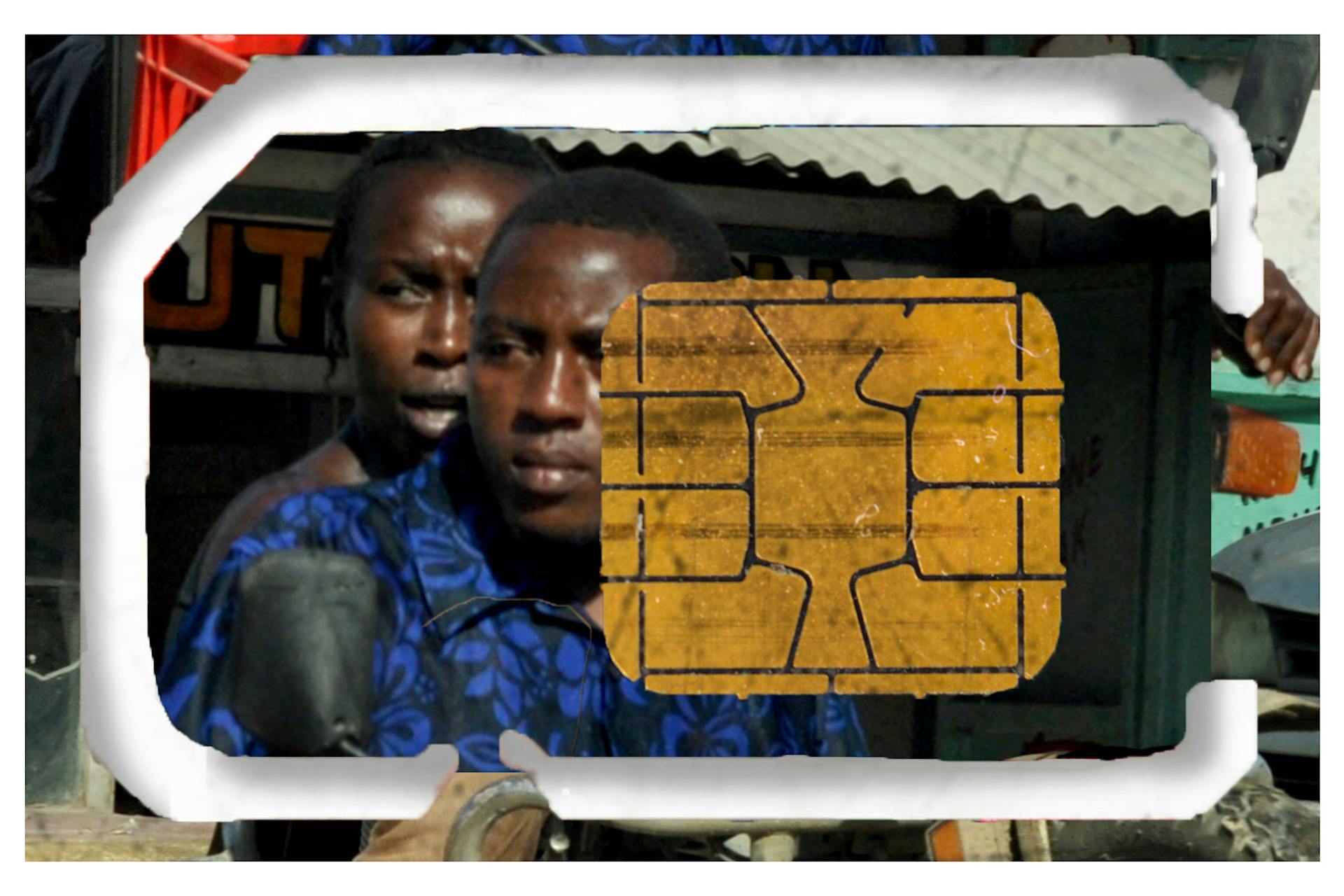

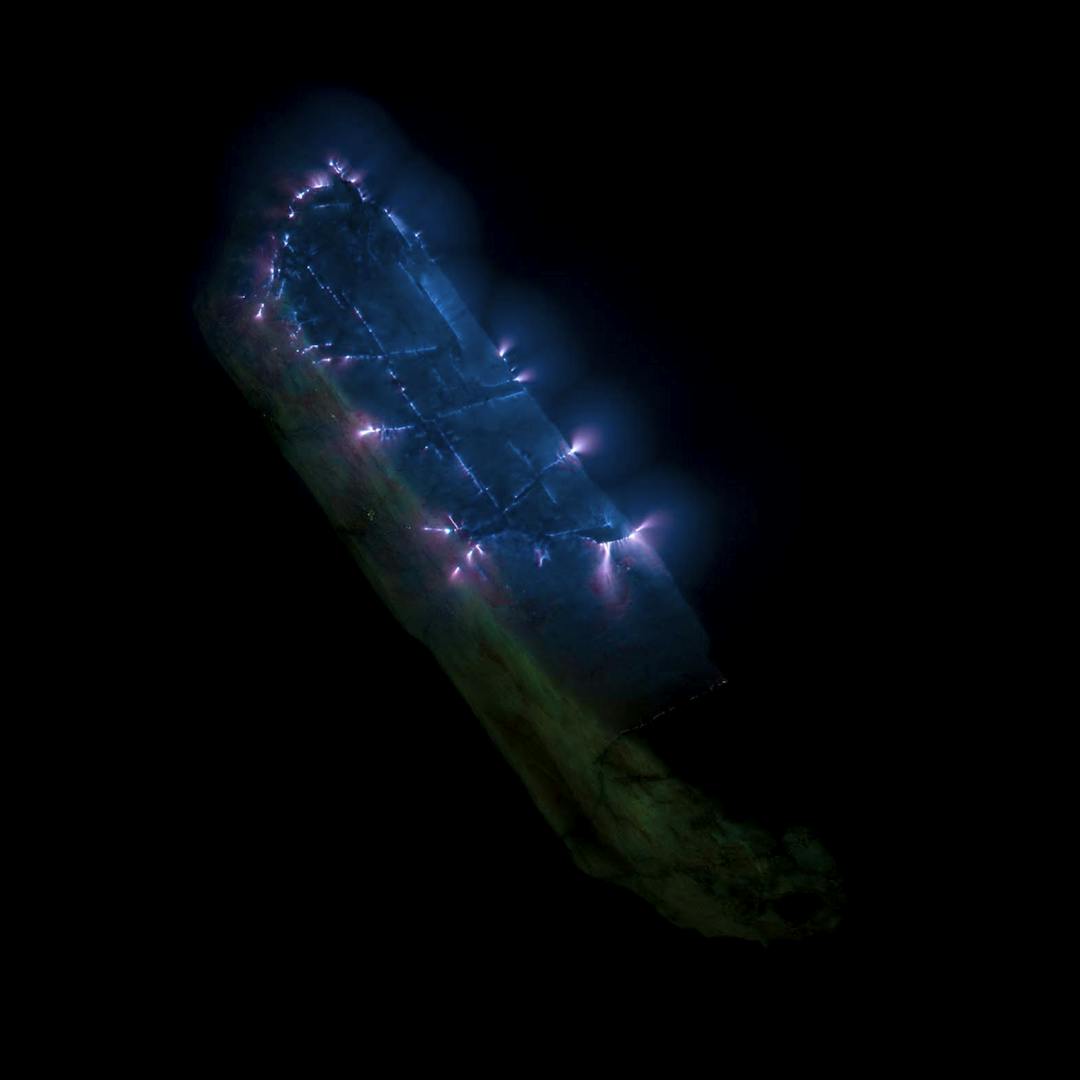

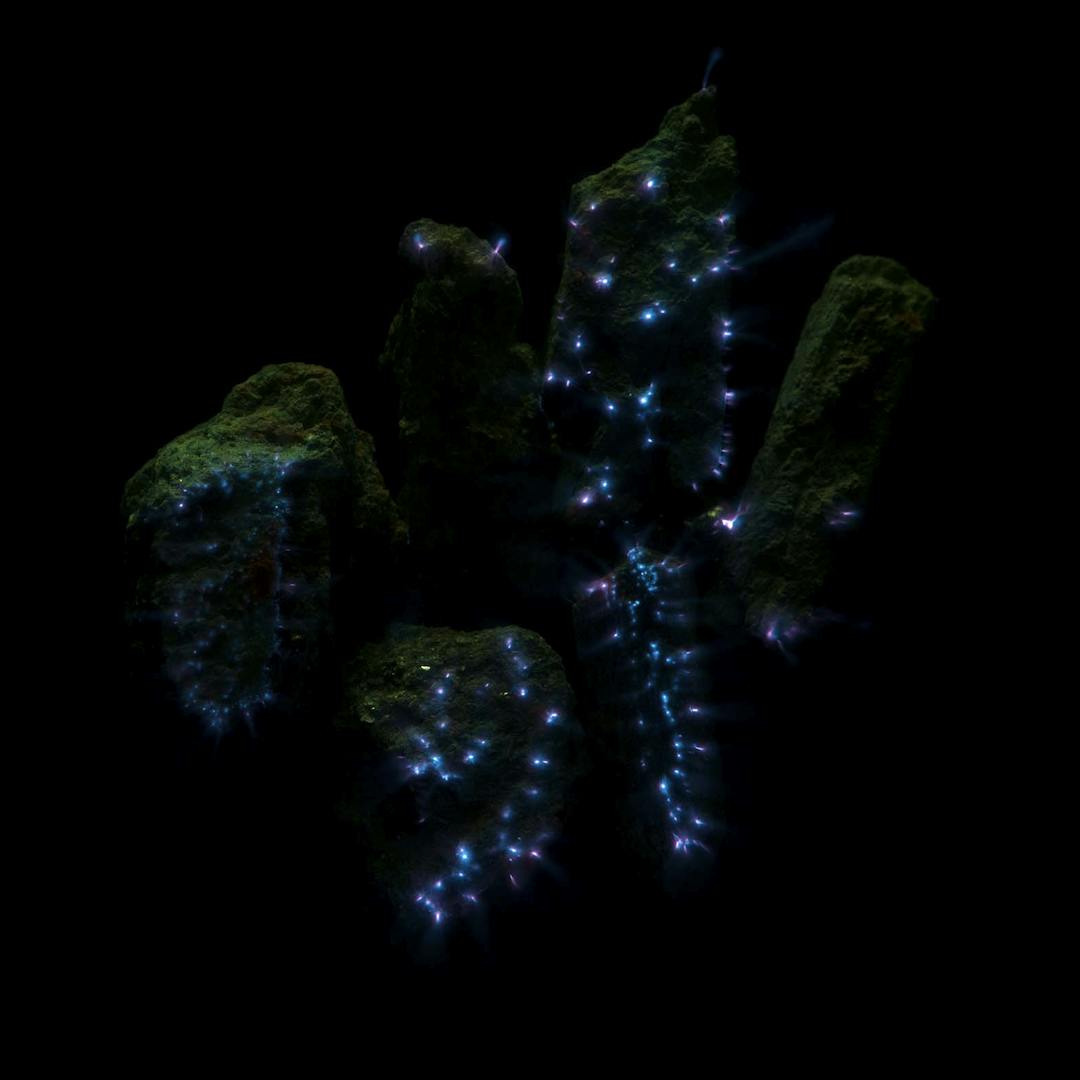

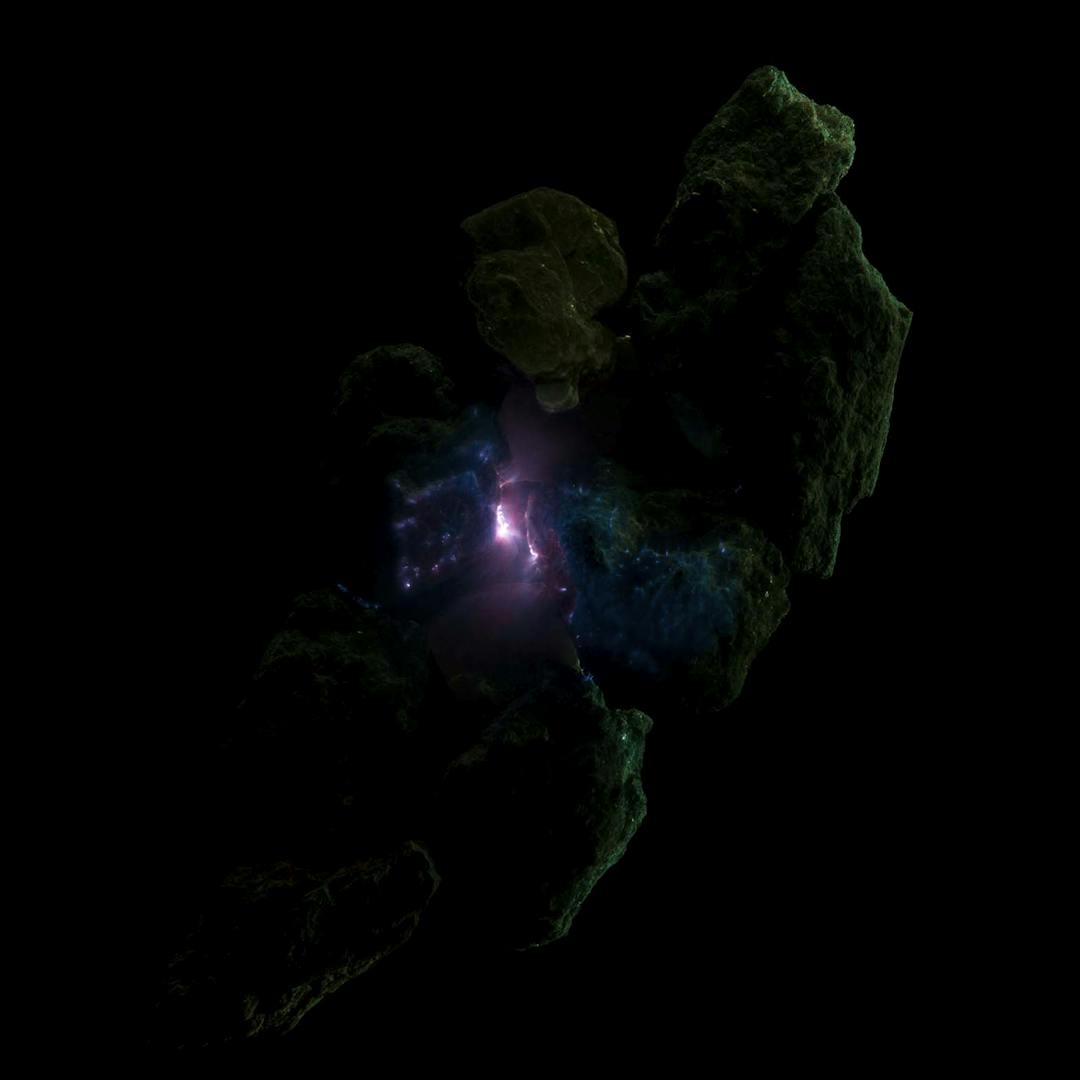

Vertical Atlas contains both visual and textual maps. It consists of new and original artworks, photo series and contributions from leading artists. Some are detailed charts; others are larger speculative drawings in diverse media and aesthetics. There are journalistic texts, poetic essays, historical studies and more academic articles.

This publication is the result of a four-year collaboration between Hivos and Het Nieuwe Instituut. It builds on the research by the Digital Earth fellows and the findings of six Vertical Atlas research labs by Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam as well as six Digital Earth workshops in Dakar, Beirut, Paris, Dubai, New Delhi and Moscow. For more information on the outcomes of the research labs, visit verticalatlas.net and digitalearth.art.